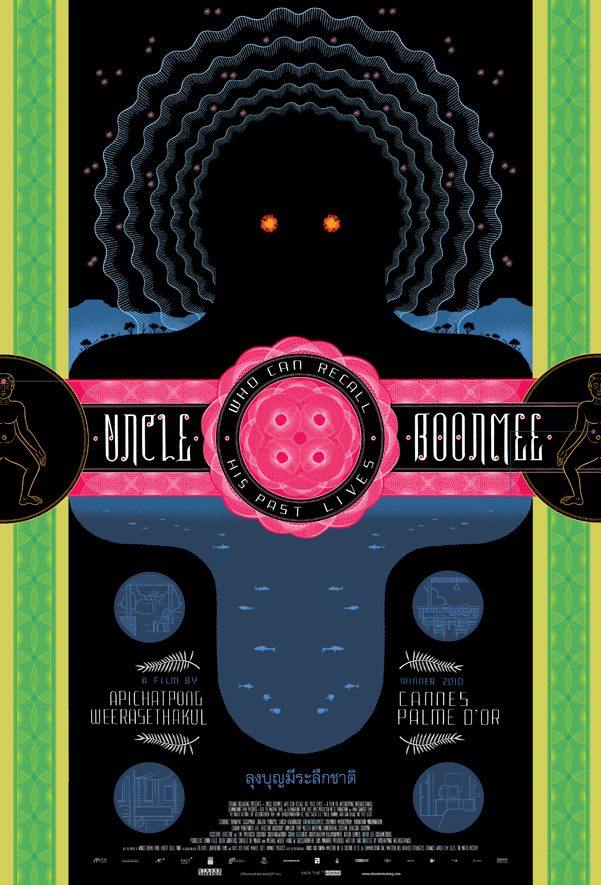

Apichatpong Weerasethakul was born in Bangkok, raised in Khon Kaen. He studied architecture at Khon Kaen University and later received an MFA in filmmaking from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He started making films and videos in 1994 and has become an independent film producer in Thailand. In 1999, Weerasethakul started his own production company Kick the Machine, and made his first feature film Mysterious Object at Noon in the following year. The artist’s unique cinematic style was already manifest in this early work, which fused the documentary with the fictional, the journalistic with the folkloric, the ghostly with the sci-fi, sensitively responding to political and social issues through a non-linear, mismatched narrative. The production house Kick the Machine does more than producing and promoting Weerasethakul’s own works; it also generously supports and promotes other independent productions and experimental films made in Thailand, and strives for Thai filmmaker’s creative distribution and screening rights. In 2002, Weerasethakul’s second feature film Blissfully Yours was awarded the prize of Un Certain Regard at the Cannes Film Festival, and this brought him international attention. His 2004 film Tropical Malady won the Cannes Jury Prize; Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives created in 2010 won the Palme d’Or from the same festival and was the first Southeast Asian film that ever received such honour.

Comparable to his achievements in film in terms of both quality and popularity, is Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s contemporary art practice, in the forms of short film, photography and video installation. For Weerasethakul, the making of a film is necessarily dependent upon a narrative, with regard to a group of audience sitting in a dark cinematic environment throughout the film, passively being hypnotised; an artistic creation, on the other hand, is far more liberating and performative, as the audience is instead placed in a free position, to be triggered and activated by the work. Weerasethakul’s short films are studies for the feature films, and also video diaries that are most personal and intimate: be it the sweaty, humid, hallucinatory tropical jungle, fragments of memory and dream chiaroscuros, Southeast Asian legends of gods and ghosts, or the cycle of spiritual life in the realms of human, plant, and animal – upon these diverse and fascinating scenes, Weerasethakul in his unique visual language constructs a series of metaphoric critiques regarding the social reality and the military junta in Thailand. He appropriates folklores and urban legends circulated in rural areas, combines them with his perspectives regarding the political and the social, and with his long-term obsession with science fictions. History through his singular lens is seemingly caught in an endless dream.

Primitive (2019) is a multi-channel video installation, focusing on the history of the border town Nabua in Thailand. Nabua was transformed into a ‘red alert zone’ in 1960s when it was occupied by the military army. In the following two decades, a large number of villagers, accused of being Communists, were brutally repressed and killed. By focusing on Nabua and its history, Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Primitive attempts to explore collective memories in northeast Thailand, and also to reflect upon his archive of personal memories. The work is at once documentary and fictional, loosely narrating the story of a group of teenagers, who are offsprings of the murdered Communist villagers. As they build a spaceship that can take the villagers to either the past and the future, the scattered video installation depicts the architectural and natural landscapes of Nabua, the young men’s playful construction project, and different moments in memory. By speaking of the repressed history of political conflicts that perpetually haunt the small town of Nabua, Weerasethakul’s work resonates with the ever-increasing tension between the Thai military junta and the working class in Bangkok in recent years. The Primitive is as much a political history of Nabua as it is a dream about ‘reincarnation and reform.’

The series of Fireworks expresses Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s political critique regarding his own country, a realm that is at once tranquil and suffocating. Geopolitically speaking, the relationship between northern provinces and the central government in Bangkok has for long been tense and confrontational. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Communism was spread from Laos to Thailand; as a result, the northern regions were brutally punished by military repressions. Weerasethakul’s Fireworks (Archive) (2014) deals with the animal statues in the Sala Keoku temple in the Thailand-Laos border town Nong Khai. The founder of the temple Luang Pu Bunleua Sulilat created these statues according to fantasies, political myths and folklores in order to preach Buddhism. However, during the Cold War in the 1960s, after being accused of a Communist, he was exiled from Thailand to Laos, and was inhumanely and unjustly treated by the political power. Weerasethakul’s work was made at night: photographs were taken as a number of actors played with fireworks. The precious joyous moment in twilight was then captured, memorised and archived. The use of flashlights and fireworks here signify flare shots and shootings in wars; in the villagers’ memory, those were at once exciting novelties, and life-threatening signs of terror. In the uncanny, flashing compositions, appearances of mysterious, horrifying statues were montaged with those of human figures, resembling resurgences of haunting memories with regard to the local fate, and also representing the re-appearance of the spectre of history. Fire brings warmth, comfort, and destruction alike.

Invisibility (2016) further developed Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s long-term interests in perception and memory. The work pertains to the pairing notions of visibility and invisibility: finding things visible in absolute darkness, is the process of dream. The audience is by the protagonist’s side, trapped in a room where there is no escape, but can only venture into each other’s dreams and shared consciousness, wandering in the overlapping realms of the visible and the invisible, the factual and the fictional, the spatial and the abyssal. Invisibility follows faithfully Weerasethakul’s artistic trajectory and reflects no less upon the turbulent situation in which Thailand has been caught. Manifestly political, the work speaks of the act of seeing, the visible and the invisible that are in reality under the military government’s control: the freedom to see and know, the freedom to knowledge and information. The work portrays a pessimistic future, in which people have to constantly avoid confronting the truth and the reality.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films and artworks are essentially the same. The political and the social are always alluded too, playing integral parts in his mysterious and poetic artistic language. By working chiefly on time and light, and by working meticulously with actors, Weerasethakul builds a delicate bridge for the audience, and allows them to travel through the real and the mythical, the individual and the collective, the spiritual and the somatic, entering via unorthodox narratives a rich consciousness, where one finds the artist’s memories, mythologies, dreams and desires.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul Chiang Mai, Thailand, B. Bangkok, Thailand, 1970

Exhibition view of “Night Particle”, Brancusi’s studio, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2024.

Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, photo by Audrey Laurans.

Exhibition view of “Night Particle”, Brancusi’s studio, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2024.

Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, photo by Audrey Laurans.

Exhibition view of “Night Particle”, Brancusi’s studio, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2024.

Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, photo by Audrey Laurans.

Exhibition view of “Night Particle”, Brancusi’s studio, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2024.

Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, photo by Audrey Laurans.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum. Photo by 近藤拓海 Takumi Kondo.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum. Photo by 近藤拓海 Takumi Kondo.

Image courtesy of the artists and Benesse House Museum. Photo by 近藤拓海 Takumi Kondo.

“Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Primitive”, M+, Hong Kong, 2024

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Photo: Dan Leung

“Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Primitive”, M+, Hong Kong, 2024

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Photo: Dan Leung

“Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Primitive”, M+, Hong Kong, 2024

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Photo: Dan Leung

“Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Primitive”, M+, Hong Kong, 2024

Image courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Photo: Dan Leung

Courtesy of the artist. @kickthemachine

Courtesy of the artist. @kickthemachine

Courtesy of the artist. @kickthemachine

Double-channel video installation, 4K, 2 synchronized videos, stereo, color

18 min 46 sec

Double-channel video installation, 4K, 2 synchronized videos, stereo, color

18 min 46 sec

Giclée print

106 x 159 cm

“A Planet of Silence , Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Kiang Malingue, Wanchai, 2022

Framed giclée Print with hand-drawn marker on glass

37.4 x 60.7 x 3.6 cm

Framed giclée print with hand-drawn marker on glass

37.4 x 60.7 x 3.6 cm

Framed giclée print with hand-drawn marker on glass

37.4 x 60.7 x 3.6 cm

“A Planet of Silence , Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Kiang Malingue, Wanchai, 2022

Giclée print

106 x 159 cm

Acrylic with silkscreen print

84.1 x 59.4 cm

“A Planet of Silence , Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Kiang Malingue, Wanchai, 2022

Double-channel video installation, SD, 4:3, silent, color

20 min

Giclée print

106 x 159 cm

“A Planet of Silence , Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Kiang Malingue, Wanchai, 2022

Double-channel video installation, 2 synchronized videos, dolby 5.1, color

11 min 3 sec

“A Planet of Silence , Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Kiang Malingue, Wanchai, 2022

Giclée Print

126.7 x 190 cm

Giclée Print, Diptych

36 x 36 cm each

Giclée Print

36 x 36 cm

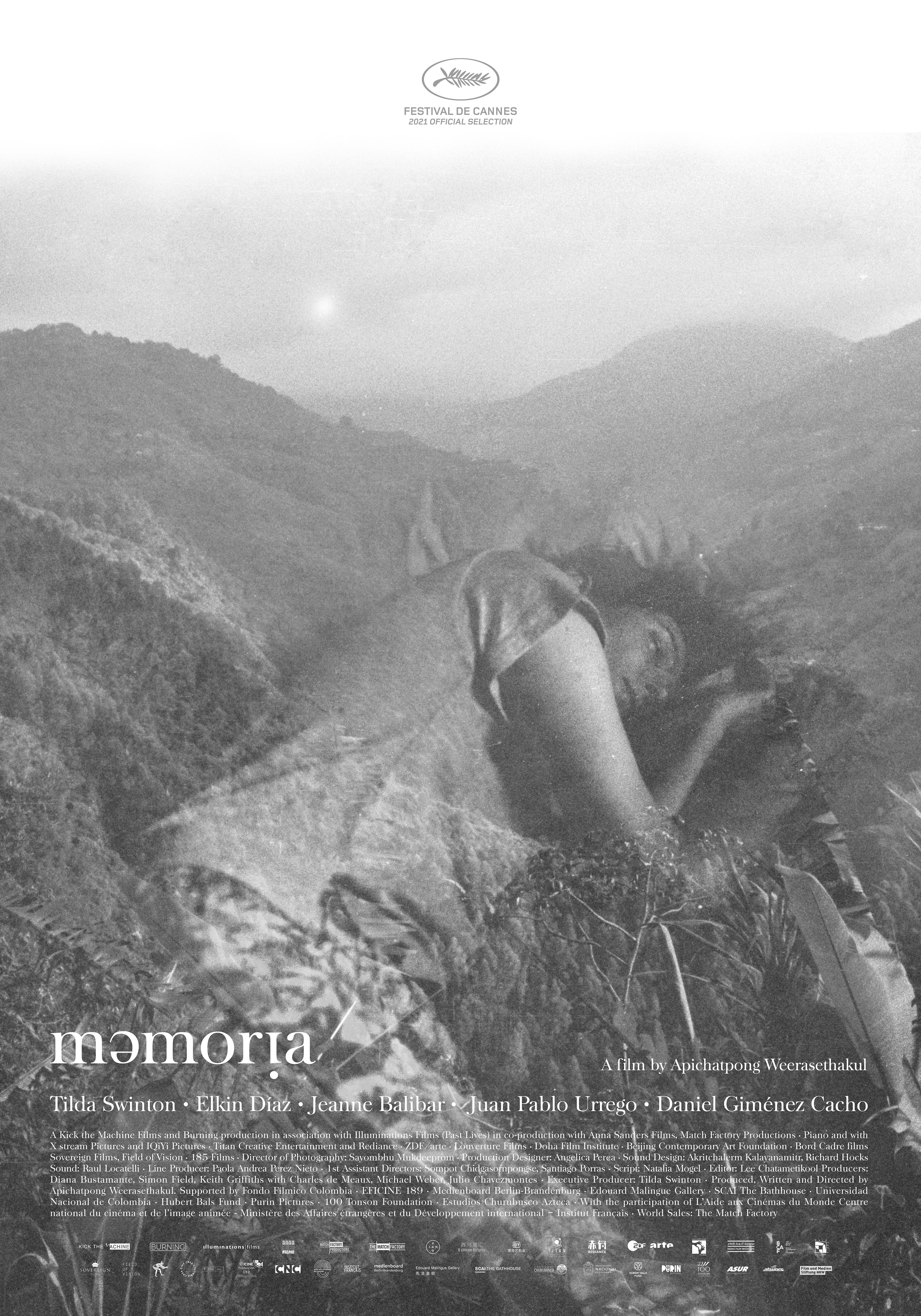

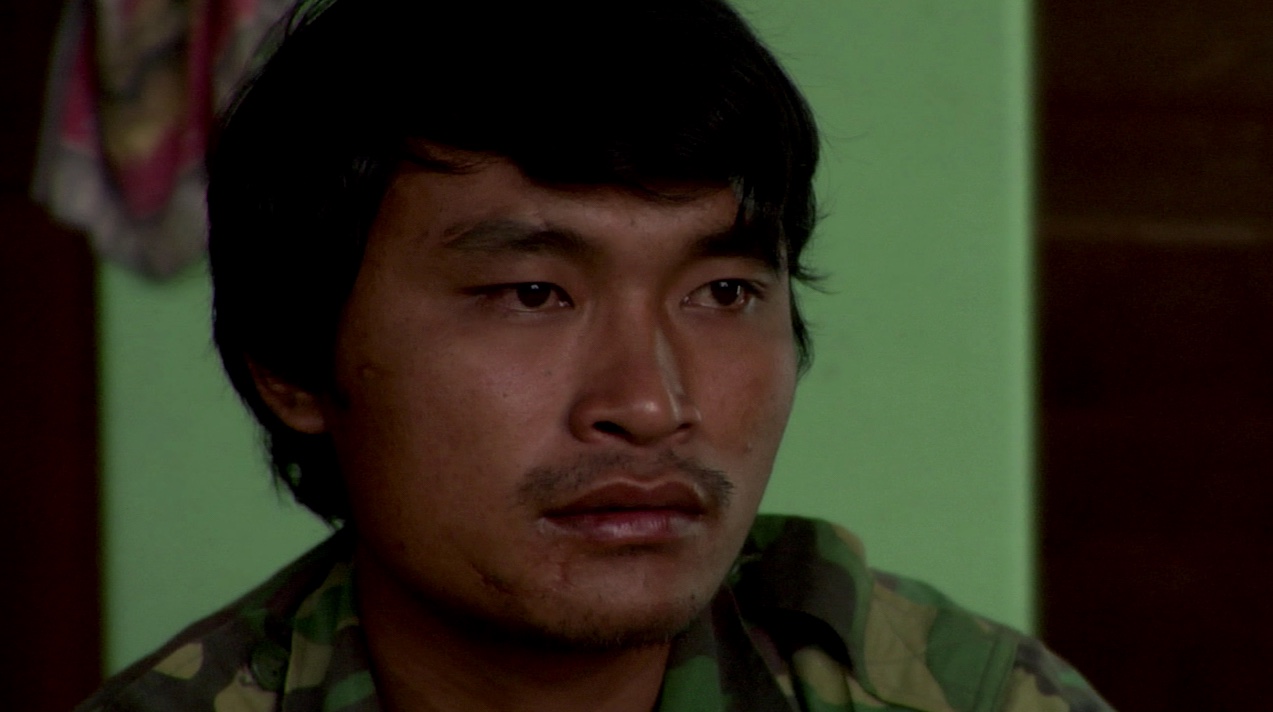

Production still

©Kick the Machine Films, Burning, Anna Sanders Films, Match Factory Productions, ZDF/Arte and Piano, 2021

Production still

©Kick the Machine Films, Burning, Anna Sanders Films, Match Factory Productions, ZDF/Arte and Piano, 2021

Production still

©Kick the Machine Films, Burning, Anna Sanders Films, Match Factory Productions, ZDF/Arte and Piano, 2021

Photo: Sandro Kopp

© Kick the Machine Films, Burning, Anna Sanders Films, Match Factory Productions, ZDF-Arte and Piano, 2021

Poster

Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Image courtesy of Kick the Machine

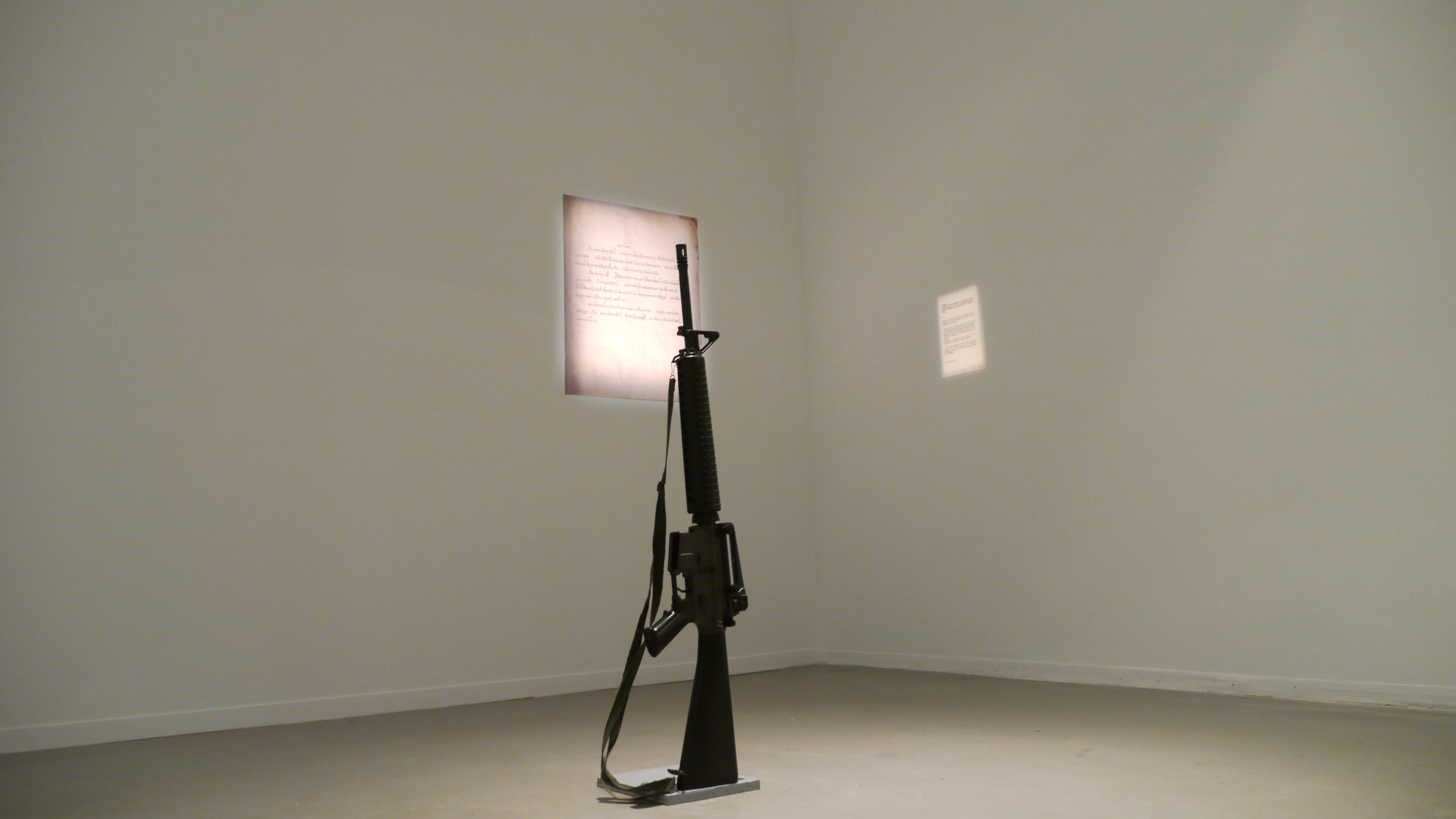

A Minor History, “Part II: Beautiful Things”, 100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022

Image courtesy of the artist

A Minor History, “Part II: Beautiful Things”, 100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022

Image courtesy of the artist

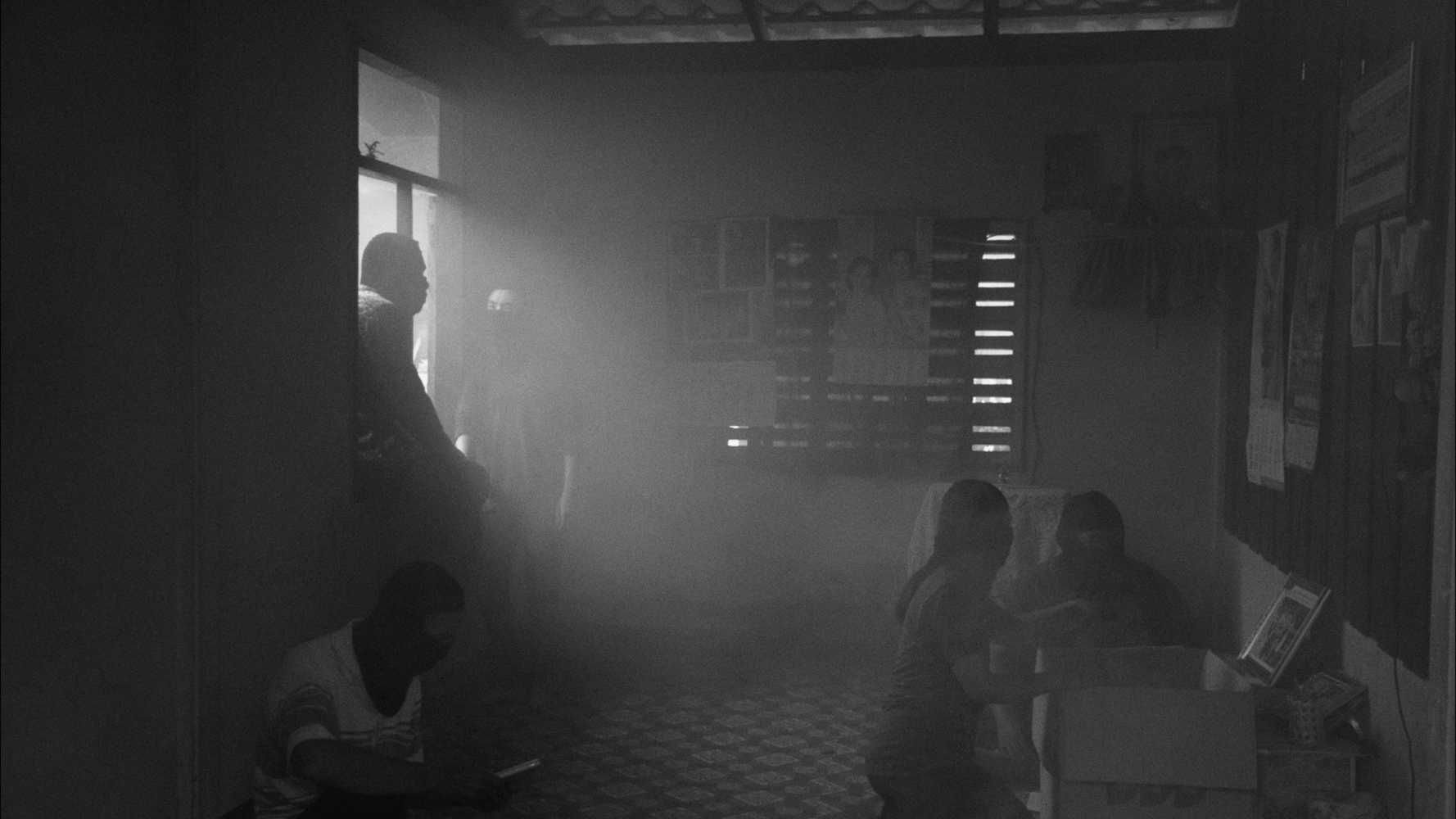

Single channel video installation. Installation view at Carriageworks for the 20th Biennale of Sydney, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok. Photo: Document Photography

Single channel video installation. Installation view at Carriageworks for the 20th Biennale of Sydney, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok. Photo: Document Photography

Single channel video installation. Installation view at Carriageworks for the 20th Biennale of Sydney, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok. Photo: Document Photography

Digital video, 21 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Digital video, 21 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Digital video, 21 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

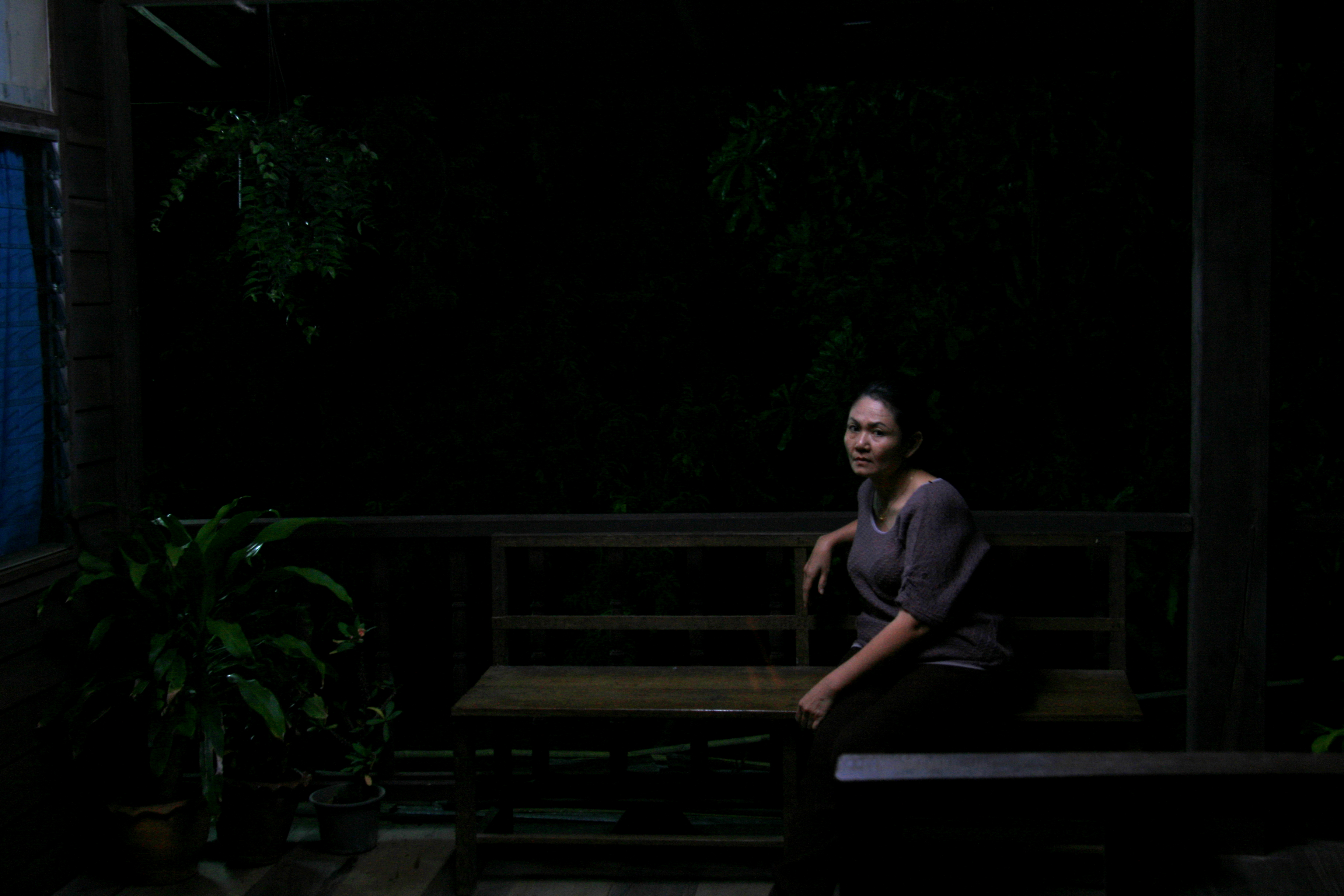

Thailand/ UK/ France/ Germany/ Malaysia, 122 min. Photo by Chai Siris. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France/ Germany/ Malaysia, 122 min. Photo by Chai Siris. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France/ Germany/ Malaysia, 122 min. Photo by Chai Siris. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France/ Germany/ Malaysia, 122 min. Photo by Chai Siris. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video installation, suspended glass pane, HD digital, B&W, 16:9, with Dolby 5.1 sound, 10 min (loop). Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films & kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Single channel video installation, suspended glass pane, HD digital, B&W, 16:9, with Dolby 5.1 sound, 10 min (loop). Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films & kurimanzutto, Mexico City

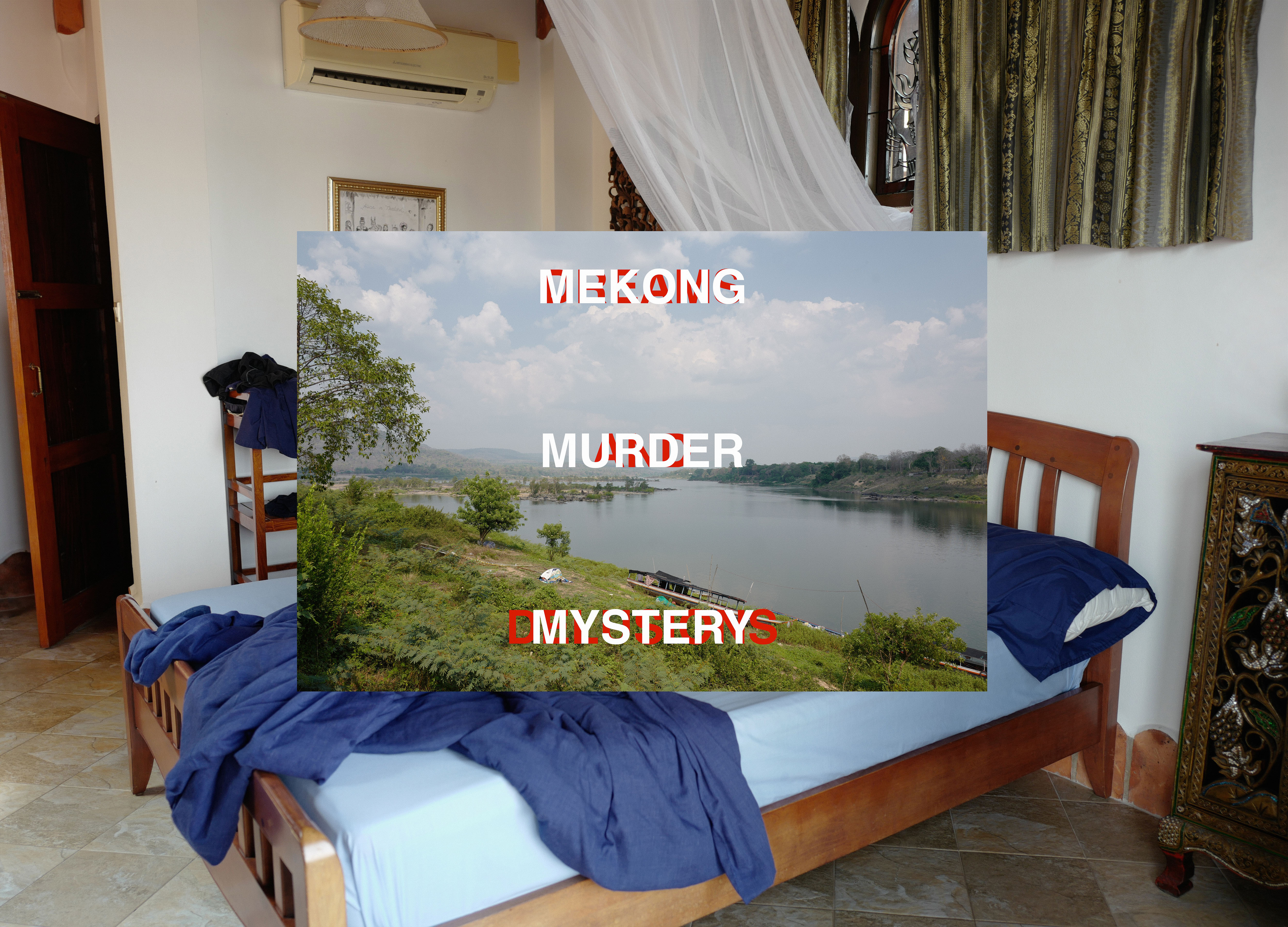

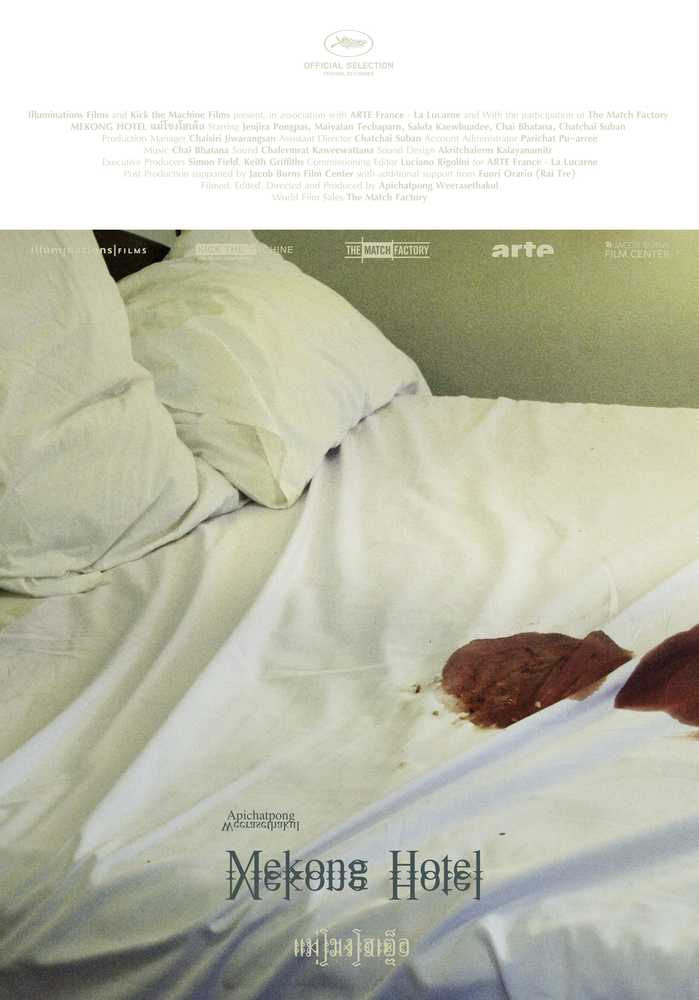

Thailand/ UK/ France, 56 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France, 56 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France, 56 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand/ UK/ France, 56 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

4 single-channel videos, 5 photographs, 1 LED speaker, 2 powered speakers, ceramic tiles. Installation view at UCCA, Beijing, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and UCCA

4 single-channel videos, 5 photographs, 1 LED speaker, 2 powered speakers, ceramic tiles. Installation view at UCCA, Beijing, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and UCCA

4 single-channel videos, 5 photographs, 1 LED speaker, 2 powered speakers, ceramic tiles. Installation view at UCCA, Beijing, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and UCCA

Photograph, 150×187.5 cm. From ‘For Tomorrow For Tonight’ project. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Photograph, 150×225 cm. From ‘For Tomorrow For Tonight’ project. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

UK/ Thailand/ Germany/ France/ Spain, 113 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video installation, colour, Dolby 5.1, 9 min 45 sec. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video installation, colour, Dolby 5.1, 9 min 45 sec. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video installation, colour, Dolby 5.1, 9 min 45 sec. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video installation, colour, Dolby 5.1, 9 min 45 sec. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Digital, 16:9, Dolby 5.1 / colour, 17 min 40 sec. Photo by Chaisiri Jiwarangsan. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Digital, 16:9, Dolby 5.1 / colour, 17 min 40 sec. Photo by Chaisiri Jiwarangsan. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2-channel synchronised video and 6 single channel videos. Installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

2 synchronized screens, colour, Dolby 5.1, 29 min 34 sec (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Photo by Chaisiri Jiwarangsan. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

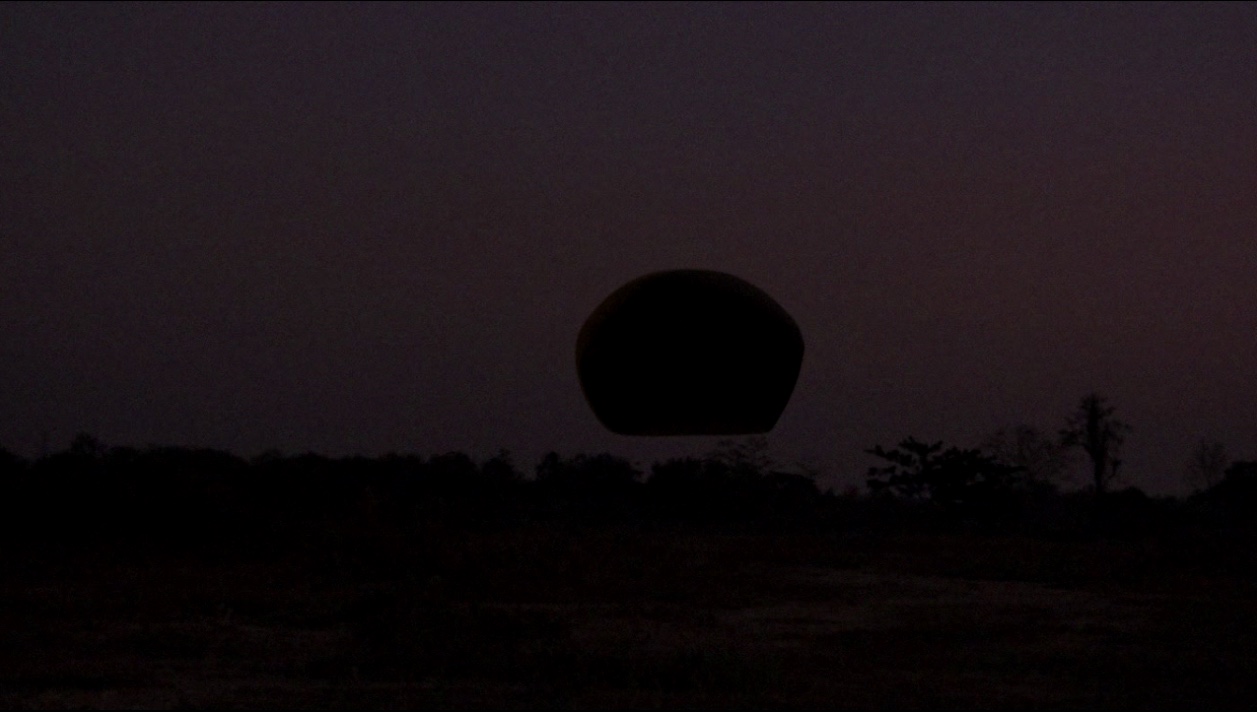

Single channel video, colour, silent, 1 min (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Image by Blursky Studio. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video, colour, Dolby 5.1, 9 min 11 sec (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Cinematography: Sayombhu Mukdeeprom. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video, silent, 4 min 10 sec (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Cinematography: Sayombhu Mukdeeprom. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video, stereo, 11 min (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Photo by Chaisiri Jiwarangsan. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Single channel video, stereo, 4 min 12 sec (looped). From ‘Primitive’ Project. Cinematography: Sayombhu Mukdeeprom. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand, digital video, 4:3, colour, stereo, 60 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films

Thailand, digital video, 4:3, colour, stereo, 60 min. Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films