Engaging with the notion of hyperreality in the digital age, Tromarama explores the interrelationship between the virtual and the physical world. Initiating as a collective in 2006 in Bandung, Indonesia, Febie Babyrose, Ruddy Hatumena and Herbert Hans create works that combine video, installation, computer programming and public participation depicting the influence of digital media on society’s perception of its surroundings. Channelling language, text, wit, sequence as well as interaction through their varied practice, Tromarama reflect on the cornerstones of Indonesia’s political and cultural environment [1], a form of perceptive engagement that applies globally.

The trio met while studying at the Institute Technology of Bandung, which since the 90s and 2000s has been active in the support of video art and the city’s creative currents. Students in respectively graphic design, advertising and printmaking, the triumvirate came together for the creation of ‘Serigala Militia’ (2006) – a stop motion animation film made of hundreds of woodcut plywood boards, flashing in speeding sequence to the beats of Seringai, an Indonesian hard rock band. This initial foray prompted years of creating playful, enigmatic stop motion animations such as ‘ting*’ (2008), ‘Bdg Art Now’ (2009), ‘Wattt?!’ (2010), ‘Pilgrimage’ (2011) and ‘The Lost One’ (2013). Through the presentation of rhythmic formations and ballet-esque movements, Tromarama creates collective journeys using everyday domestic objects, which in turn shed light on the rituals of everyday life.

From the beginning, Tromarama’s body of work has equally extended to video and installation. ‘Borderless’ (2010), as an early example, comprises a video made of embroidery on canvas, addressing the commonplace and domestic. ‘Private Riots’ (2014), reformulated and presented at Art Basel Encounters in 2016, marks a comparatively political leaning and presents playful pop-like extractions of key images from protest banners; time, marching, speeches. Alongside, a post-it board in 2014 invited passers-by to mark and share their own frustrations or commentary. A key turning point, however, was 2015, marked by the solo exhibition ‘Panoramix’ (2015). Over the course of several video works and lenticular prints, Tromarama zoned in on their investigation of the digital world, its impact on our apprehensions of reality, and laid out some of the key cornerstones of their future practice: wit, interaction and language.

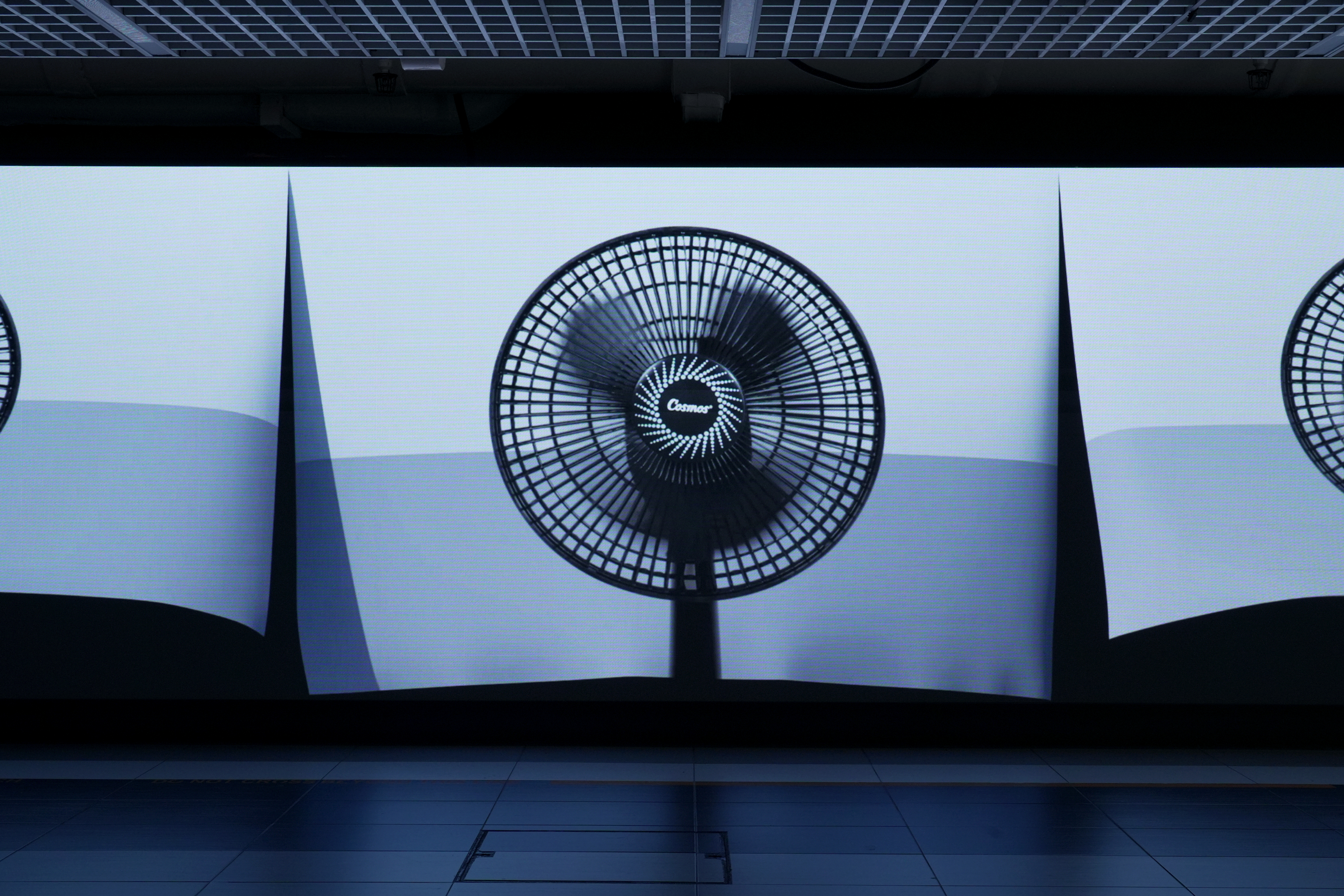

Play, in the sense of ‘fresh, intriguing and humorous’ [2] has always been identified as an important aspect of Tromarama’s practice. The evolution to wit, however, is slightly more subtle and explorative of cause and effect. The double-channel film ‘Intercourse’ (2015), for example, presents on one screen a stand-up fan facing a projected series of larger-than-life fluttering objects: bonsai tree, tissue, phone book, etc. The relationship is clear despite the live-time probability being incredulous. Yet, you halt in your step, mentally-respectful of the digitally-created visual cause and effect. Further examples include ‘Quandary’ (2016) depicting an object moving gravitationally between two locations and screens despite these being different; ‘Transitivity’ (2016) showing plant growths and changes ‘overnight’ with every switch of a lightbulb; ‘Propinquity’ (2017) in which various protagonists, as only revealed by their shoes, hop between parallel screens. Throughout there is a push and pull between actual and digital reality, the possibilities of occurence.

Indeed, at the heart of Tromarama’s body of work is interaction: whether between elements in the work itself and/or in relation to the viewer. The running series of lenticular prints, such as ‘Posed’ (2017), ‘Classroom’ (2016) and ‘I Do’ (2015), for example, involve discovery by reading the subtitled ‘screens’ in three parts: as one views the work face on, then from one side and another. The effect is one of individual meaning yet collective communication, a reflection on whether what one sees from a single angle is truly ‘it’. More directly involving human interaction, ‘Circuit’ (2017) is composed of a pulse sensor that engages with visitors and is connected to a video projection. This emphasis on interaction, however, is also within the works themselves. A major example of this is the recent installation ‘Soliloquy’ (2018) commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art & Design (MCAD) in Manila, Philippines in which a collection of lightbulbs light up a room. In clustered arrangements, they flash in ad hoc yet sequential unison. Powered by a software collaboratively created by Tromarama, the work engages the public not only visually but also through the realm of social media, centring on the hashtag of ‘kinship’.

This relationship with language, generally but also specially through the realm of social media, is an important aspect of Tromarama’s recent practice. ‘24 Hours Being Others’ (2017) presents three stacked printers connected by a software that collects tweets associated with each term in the work title and then sends them for print through the machines on take-away A5 pieces of paper. The result is akin to a poem, the font being in Times, the connection to someone unknown yet of this world enigmatically intimate. This textual manner of engaging with the digital realm has been reformulated in later works such as ‘Self Portrait’ (2018), ‘Wave Forecast’ (2018) and ‘Wave Forecast No.2’ (2018) each time highlighting different terms that connect to ourselves and others, whether ‘portrait’, ‘listening’ or ‘privacy’. In an age of digital anonymity and mass interconnectivity, Tromarama create pockets of direct relationship with others using social media and its language as a medium.

At the heart of Tromarama’s practice is the creation of narratives, the ones that can and could exist within our physical and digital worlds, but perhaps more crucially, those that exist when we fuse the two. Their works explore the new cornerstones of social constructs as defined by an evolving age; the spectrums of connectivity and shifting notions of reality. A topic, which ultimately, they tackle with play, warmth and a sense of curious empathy.

Tromarama are widely considered one of Indonesia’s most exciting rising talents and have been exhibited around the world. They have held solo exhibitions at Centre A, Vancouver (2017); Liverpool Biennial Fringe, Liverpool (2016); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2015); National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (2015); and Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2010) among other locations. Their group exhibitions include the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) Manila (2018); Singapore Art Museum, Singapore (2017); Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju (2016) ; Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt (2015); Samstag Museum of Art, Adelaide (2014); and the 7th Asia Pacifc Triennial of Contemporary Art, Brisbane (2012).

[1] Enin Supriyanto, ‘How to Turn Trauma into Video Art: A Brief History of Tromarama’, for “MAM Project 012: TROMARAMA” catalogue, published by Mori Art Museum, (August 1 2010)

[2] Alia Swastika, ‘When Playing Is Not Only a Game’, (2011)

Tromarama Jakarta and Bandung, Indonesia, B. Bandung, Indonesia, 2006

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Tromarama, Turn On, 2026, single-channel video, sound 14 min 42 sec.

Commissioned by NTU Museum.

Installation view of “On the cusp”, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2026.

Installation view of Open Studios: Les rencontres de Montmartre, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Installation view of Open Studios: Les rencontres de Montmartre, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Installation view of Open Studios: Les rencontres de Montmartre, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Installation view of Open Studios: Les rencontres de Montmartre, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Tukar guling, 2023

Haptic devices, custom computer program, router, dimensions variable

Installation view of Open Studios: Les rencontres de Montmartre, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artists.

Single channel video

1 min 34 sec

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

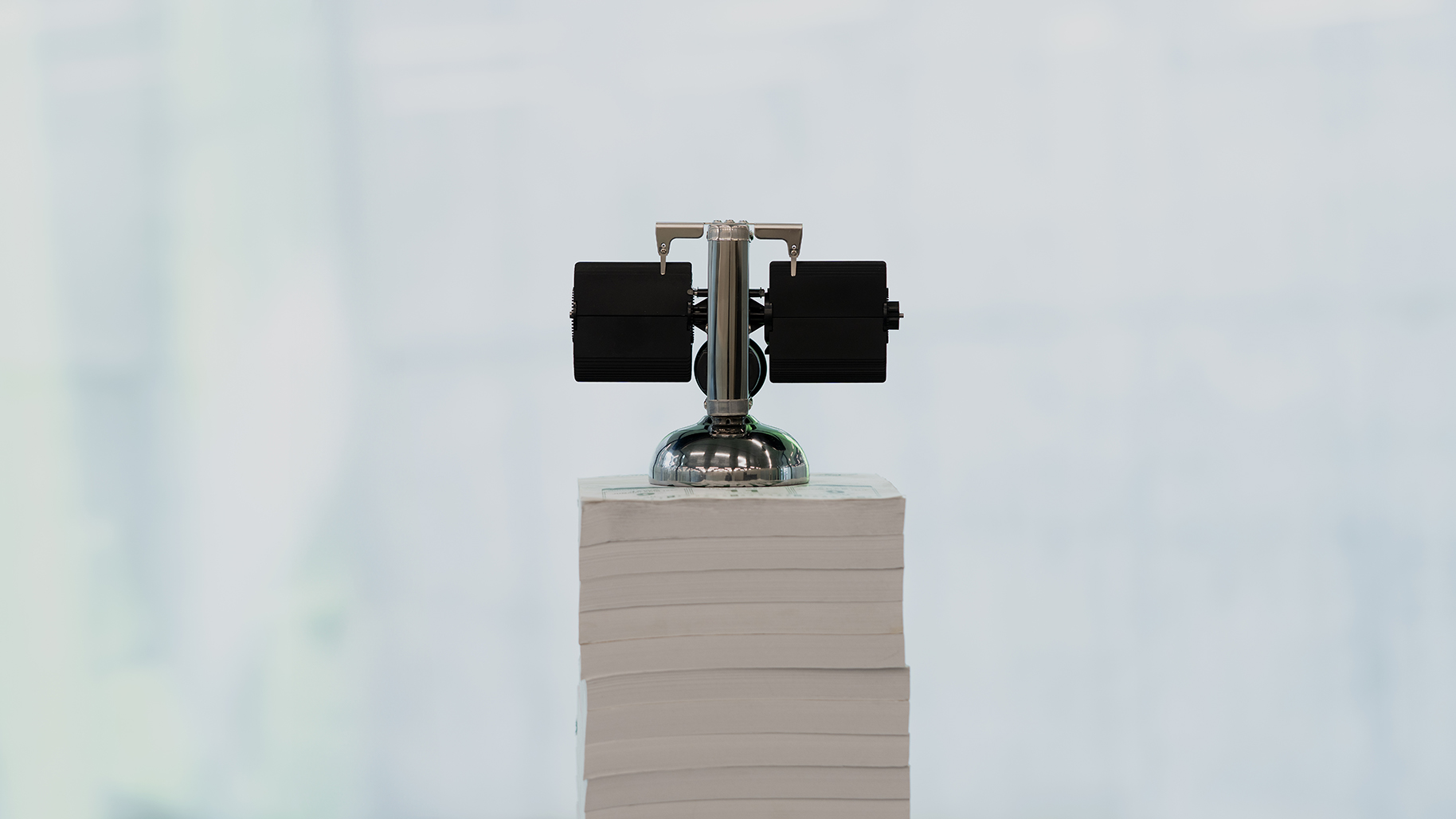

Clock, calendar Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Clock, calendar Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Printer, paper, custom computer program, #24hours, #being, #others

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Printer, paper, custom computer program, #24hours, #being, #others

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Instant noodle cup, speaker, mini PC, monitor, magic arm, custom computer program, #force

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Instant noodle cup, speaker, mini PC, monitor, magic arm, custom computer program, #force

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Instant noodle cup, speaker, mini PC, monitor, magic arm, custom computer program, #force

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

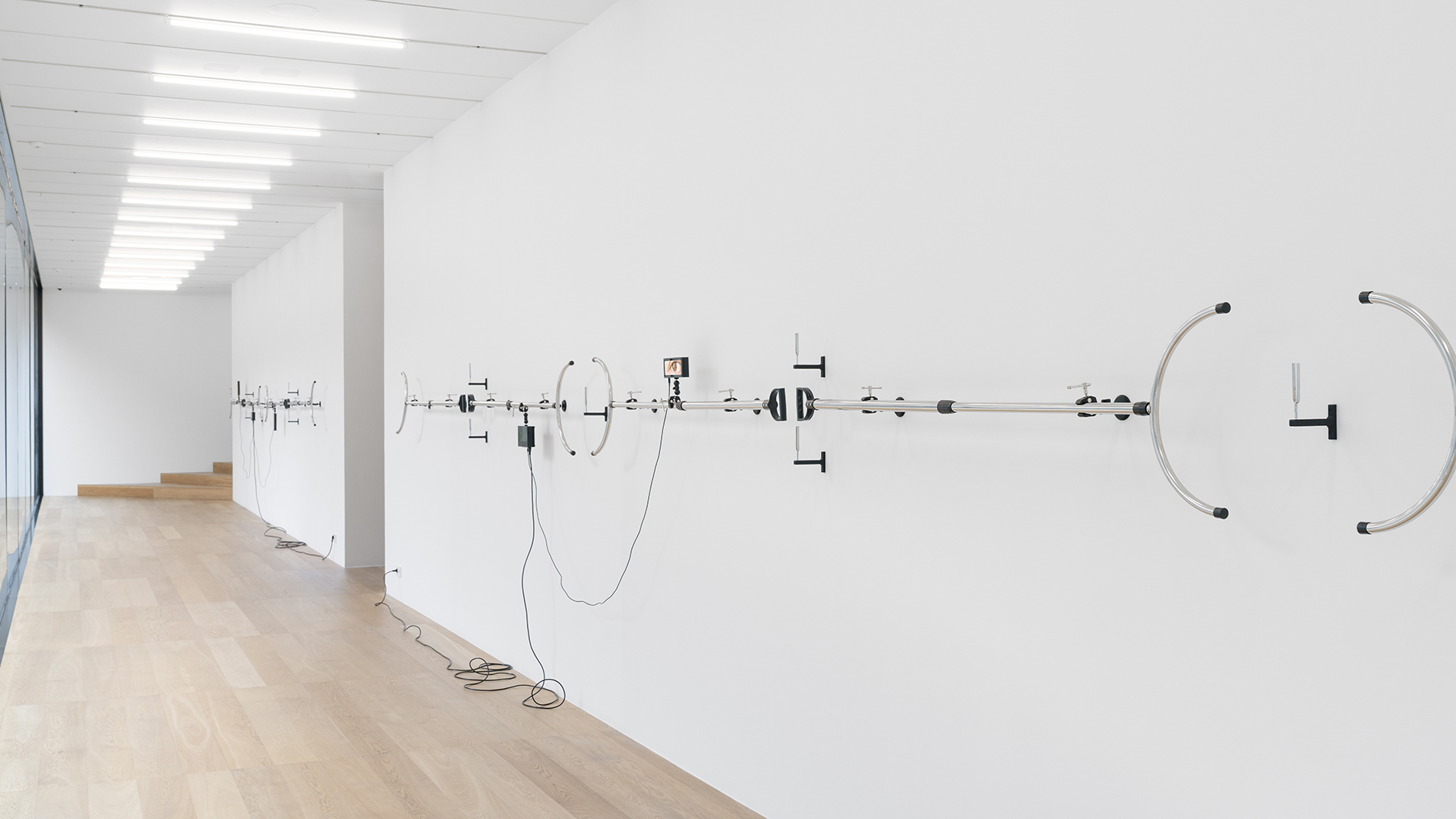

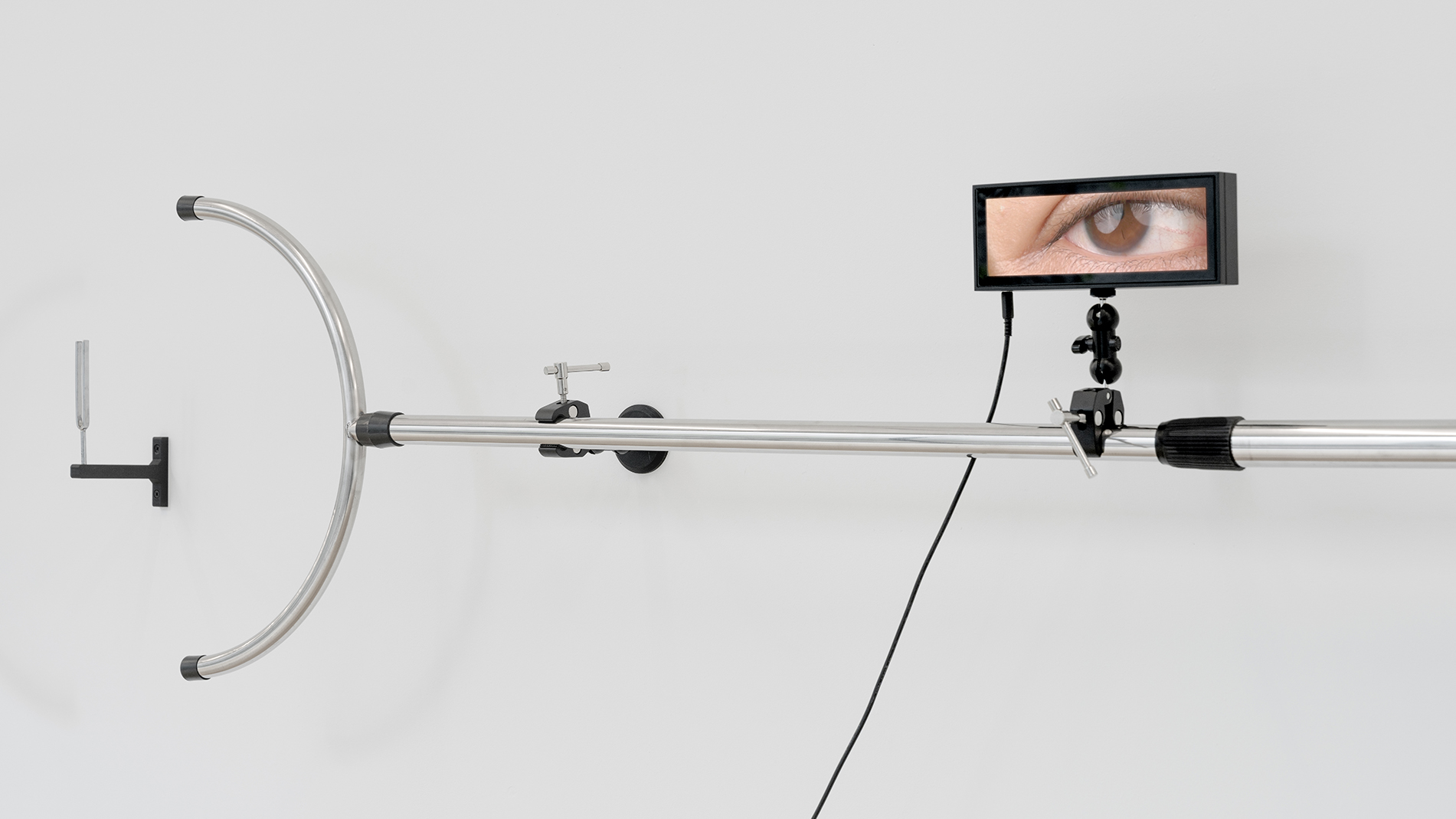

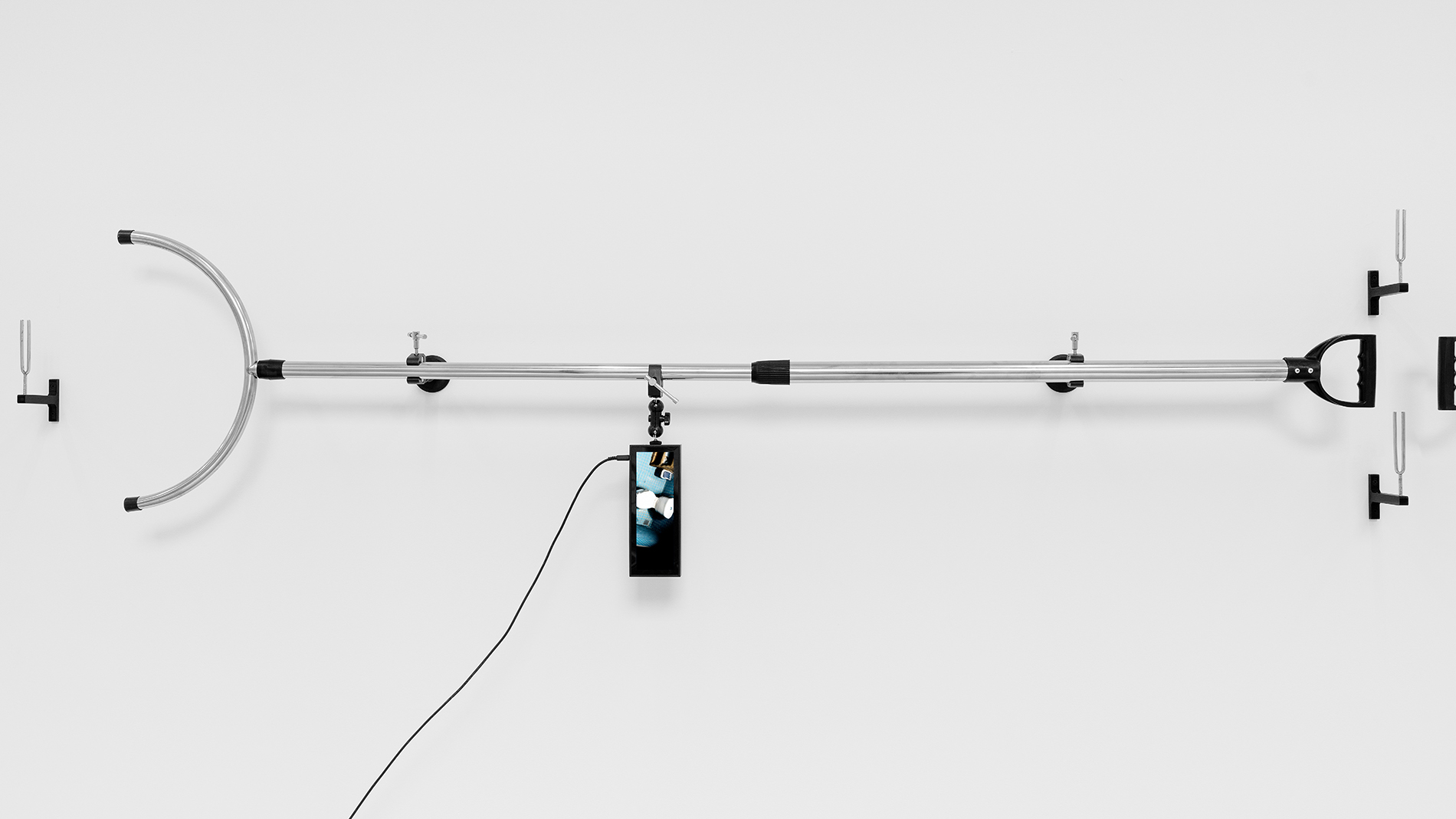

Waist fork, tuning fork, monitor, magic arm, clamp Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Waist fork, tuning fork, monitor, magic arm, clamp Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Waist fork, tuning fork, monitor, magic arm, clamp Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

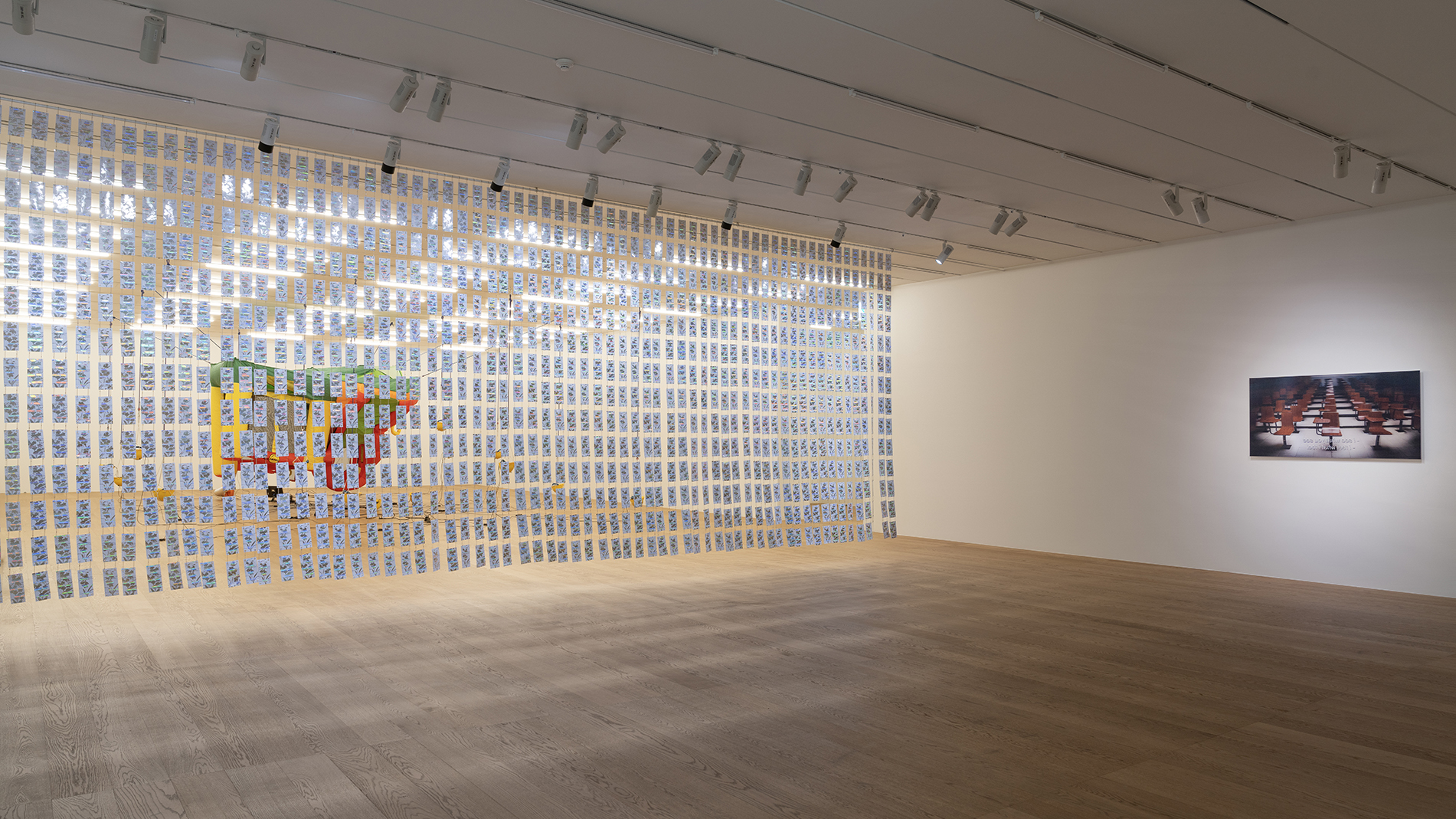

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Foil hot press on attendance record cards, ball chains, iron pole

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Inflatable castle, speaker, construction helmet, paracord, mini PC, custom software, #assignment

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Inflatable castle, speaker, construction helmet, paracord, mini PC, custom software, #assignment

Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Two-channel video, sync, sound 3 min 47 sec

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

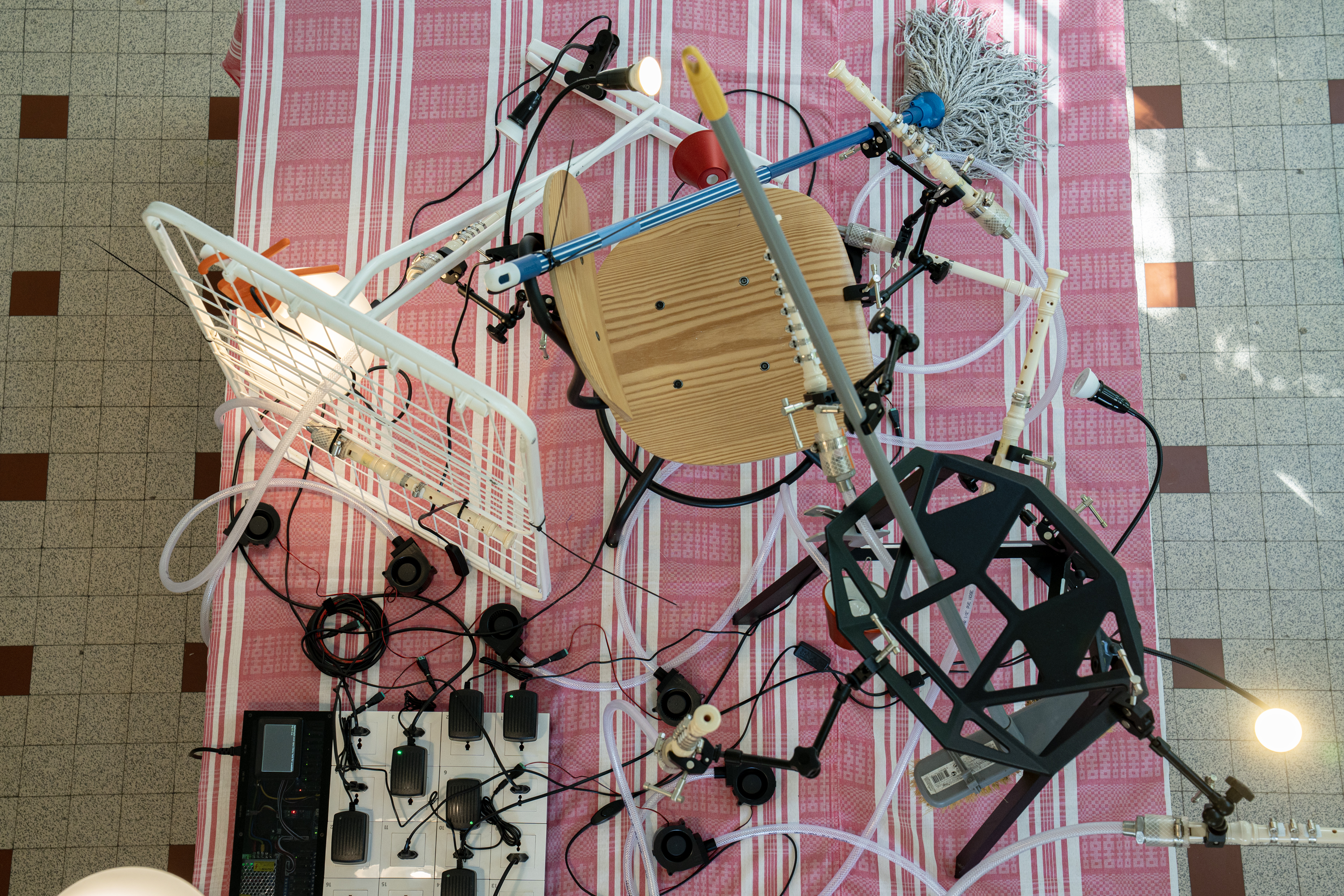

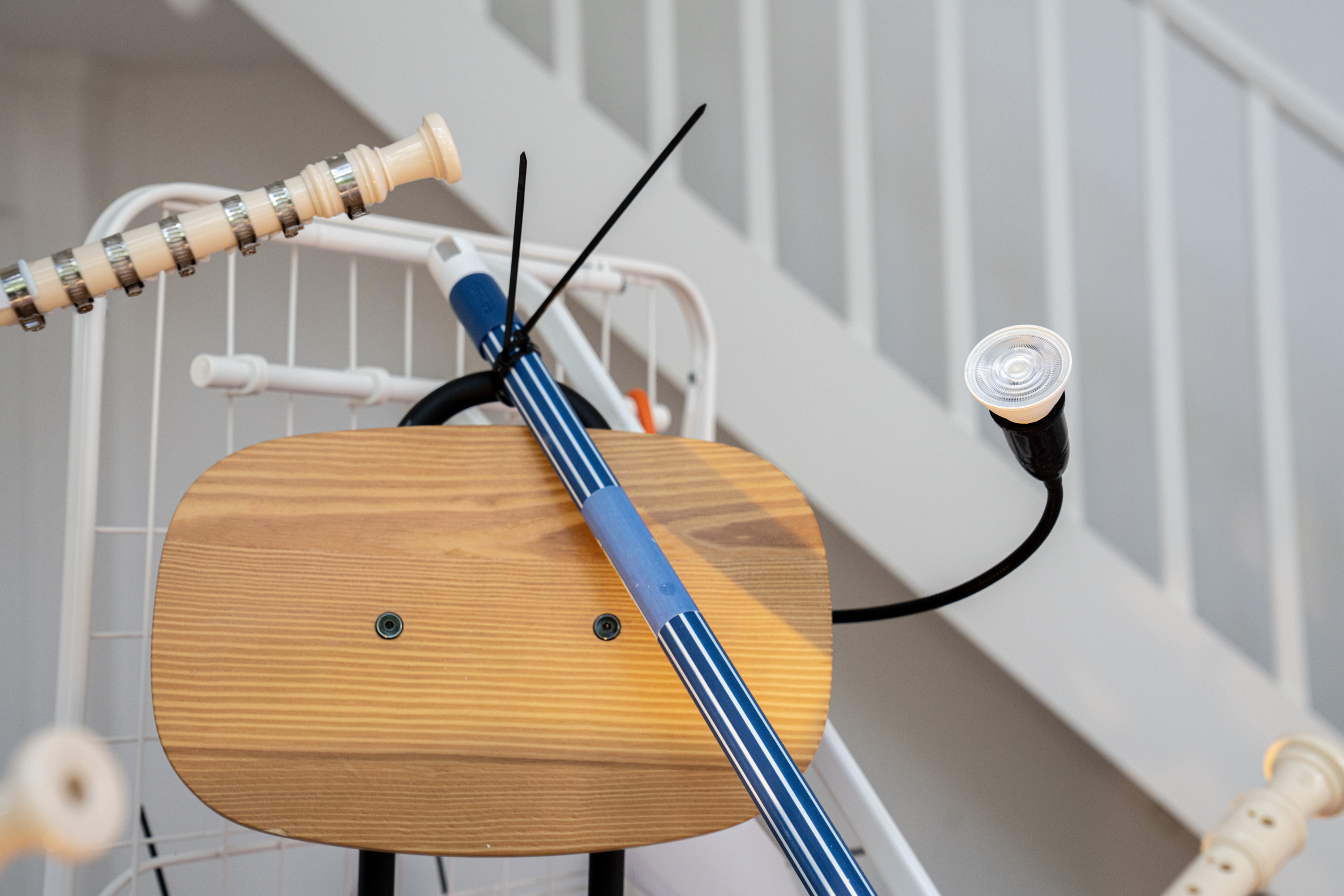

Soprano Recorder, melodica, bar chime, construction pole, DC Fan, hose, hose clamp, custom computer program Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Soprano Recorder, melodica, bar chime, construction pole, DC Fan, hose, hose clamp, custom computer program Dimensions variable

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Activation performance, haptic devices, balls, bekel seeds, nets, network software

Dimensions variable, performance: 60 min

Installation view, “Ping Inside Noisy Giraffe”, SONGEUN, Seoul, 2025.

Image courtesy of the artist and SONGEUN, photo by Studio Jaybee.

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Himalayan salt lamp, custom computer program

Dimensions variable

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

150 x 150 cm

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

150 x 150 cm

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Single channel video

1 min 34 sec

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Two channel video, sync

3 min 47 sec

Installation view, 10×10 Masters of Asia Art Season, Dafen Museum, Shenzhen, 2024.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Himalayan salt lamp, custom computer program

Dimensions variable

Installation view of “The Threshold under Turbine Vents”, Sun Blanket Foundation, Seoul, South Korea, 2024.

Image courtesy of Sun Blanket Foundation.

Himalayan salt lamp, custom computer program

Dimensions variable

Installation view of “The Threshold under Turbine Vents”, Sun Blanket Foundation, Seoul, South Korea, 2024.

Image courtesy of Sun Blanket Foundation.

Himalayan salt lamp, custom computer program

Dimensions variable

Installation view of “The Threshold under Turbine Vents”, Sun Blanket Foundation, Seoul, South Korea, 2024.

Image courtesy of Sun Blanket Foundation.

Commissioned by M+, 2023.

Courtesy of Tromarama.

Photo: Moving Image Studio M+, Hong Kong.

Commissioned by M+, 2023.

Courtesy of Tromarama.

Photo: Moving Image Studio M+, Hong Kong.

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Himalayan salt lamp, custom computer program, dimensions variable

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Foil hot press on attendance record card, magnet, iron

157.5 x 99 cm (each)

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Foil hot press on attendance record card, magnet, iron

98.5 x 205 cm

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Single channel video

6 min 3 sec

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Kinetic sand, dimensions variable

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Haptic devices, custom computer program, router, dimensions variable

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Haptic devices, custom computer program, router, dimensions variable

‘Contraflow’, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, 2023

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

180 x 120 cm

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

180 x 120 cm

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

180 x 120 cm

“Tao Hui, Tromarama, Wang Zhibo”, Stevenson Gallery, Amsterdam, 2023.

Image courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Foil hot press on the attendance record card, iron

A set of 6 panels, each panel 57 x 43.5 cm

Overall: 114 x 130 x 2.5 cm

Latex mask, speaker, mini pc, monitor, metal pipe, custom software

Dimensions variable

On display in NGV Triennale 2020 from 19 December – 18 April 2021 at NGV International Melbourne

Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria

Photo by Tom Ross

On display in NGV Triennale 2020 from 19 December – 18 April 2021 at NGV International Melbourne

Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria

Photo by Tom Ross

On display in NGV Triennale 2020 from 19 December – 18 April 2021 at NGV International Melbourne

Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria

Photo by Tom Ross

On display in NGV Triennale 2020 from 19 December – 18 April 2021 at NGV International Melbourne

Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria

Photo by Tom Ross

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

180 x 120 cm

Lenticular print, mounted on aluminium dibond

180 x 120 cm

Digital image projection, software, real-time internet-based data, and sound, variable dimensions

Digital image projection, software, real-time internet-based data, and sound, variable dimensions

Melodica, C-clamp, Rope, Soprano Recorder, Stand Mic, DC Fan, Hose, Hose Clamp, Chains, Digital Print on Fabric, Software, Social Media, Variable Dimension

Installation view at Paris Internationale, 2019

Image courtesy of the artist and ROH Projects

‘Soliloquy’, 2018

Lamps, software, social media, wood pallet, #kinship

Image courtesy of the artist

Image courtesy of the artist

Image courtesy of the artist

Image courtesy of the artist

2017

‘Amphibia’,

Centre A, Vancouver, Canada, 2017

‘Amphibia’,

Centre A, Vancouver, Canada, 2017

‘Amphibia’,

Centre A, Vancouver, Canada, 2017

2017

Five channel video, computer generated editing

‘Amphibia’,

Centre A, Vancouver, Canada, 2017

2015

Installation view at Gwangju Biennale

2016

Installation view at Gwangju Biennale

2016

Single channel video

5 min 2 sec

Installation view at Liverpool solo exhibition

2016

3D lenticular print

80 x 150 cm

2015

Two channel video

4 min 10 sec

Installation view at Liverpool solo exhibition

2015

3D lenticular print

80 x 150 cm

2015

Lenticular print

62 x 110 cm

2015

installation view at Edouard Malingue Gallery

2015

installation view at Edouard Malingue Gallery

2015

installation view at Edouard Malingue Gallery

2015

installation view at Edouard Malingue Gallery

2015

installation view at Edouard Malingue Gallery

2015 – Single channel video – 1 min 29 sec

2015 – single channel video – 2 min

2015 – Video animation, Towel, Wire – Variable dimension

2015 – Two channel video – 4 min 10 sec

2014 – Single channel video – 8 Digital print on cotton

2014-2016

Video animation, board, pen

2 min 40 sec

2014

ABatavia

Video projection, 30 Screen print on t-shirt

2014

ABatavia

Video projection, 30 Screen print on t-shirt

2014

Single channel video

3 min 54 sec

2014

Single channel video

3 min 54 sec

2014

Single channel video

3 min 54 sec

2014

Single channel video

07 min 05 sec

Sound by Blacksmith

2013

Video animation with shoes

03 min 16 sec

2013

Video animation with shoes

03 min 16 sec

2013

Video animation with paper cut and scanned fabric

03 min 07 sec

Sound by Bagus Pandega

2013

Video animation with paper cut and scanned fabric

03 min 07 sec

Sound by Bagus Pandega

2012

30 decal on plate, video projection, animation loop

2011

Stop motion animation with various objects

4 min 18 sec

Installation view at Liverpool solo exhibition

2010

Video animation with Embroidery on Canvas

2 min 25 sec

2008

Stop motion animation with porcelain tableware

2 min 47 sec

Sound by Bagus Pandega

2006

Stop motion animation with woodcut plywood boards

4 min 22 sec