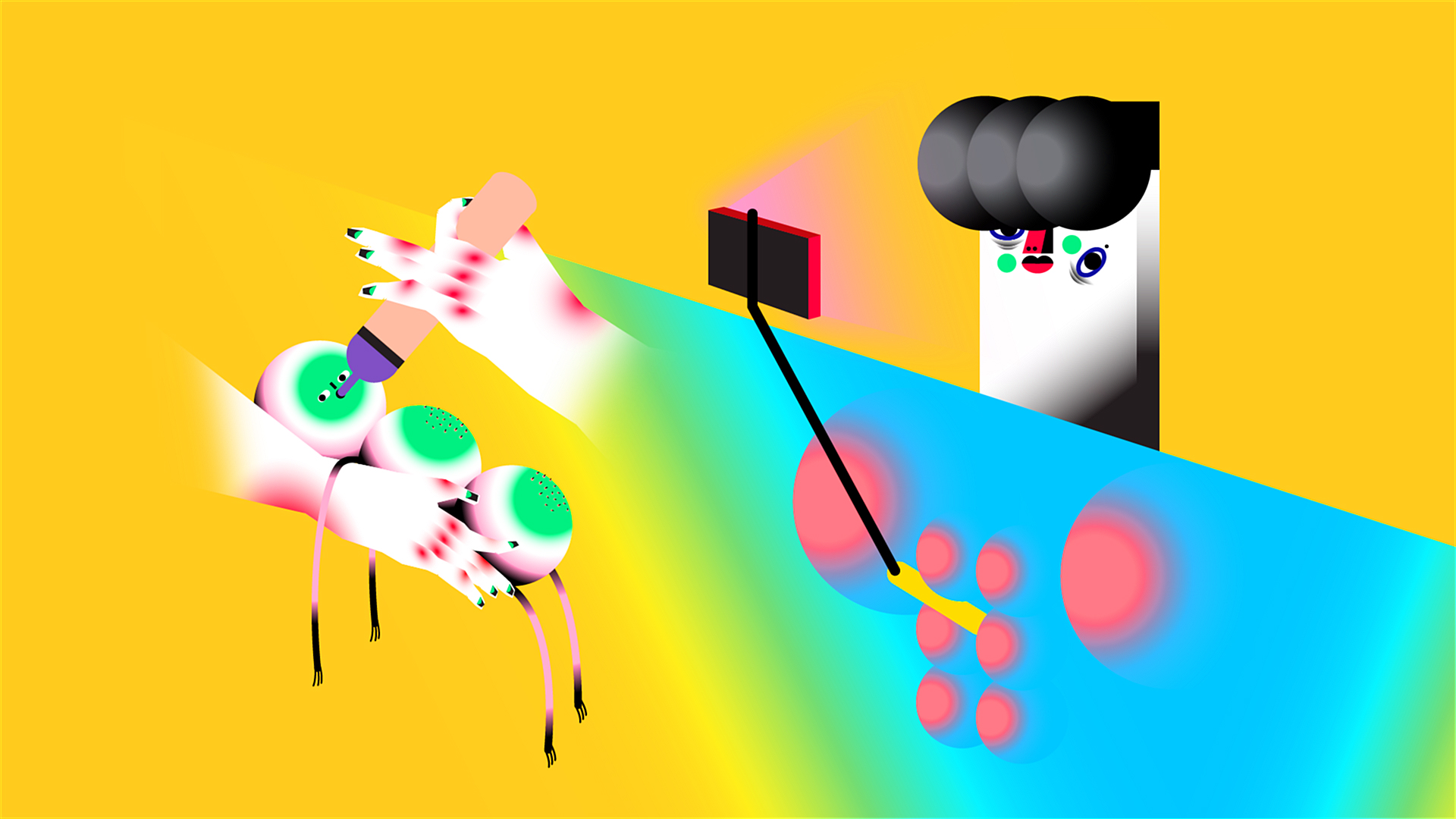

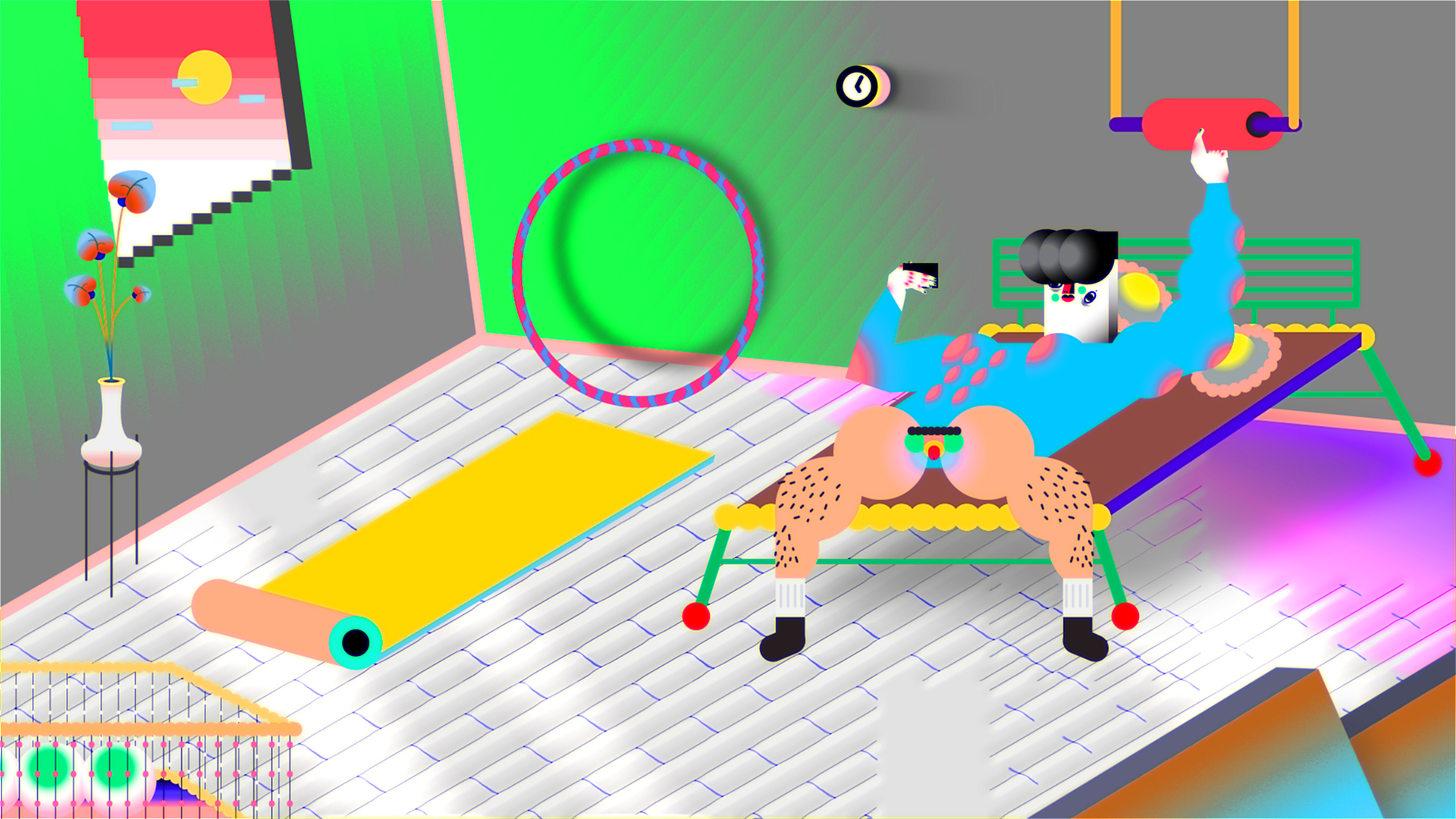

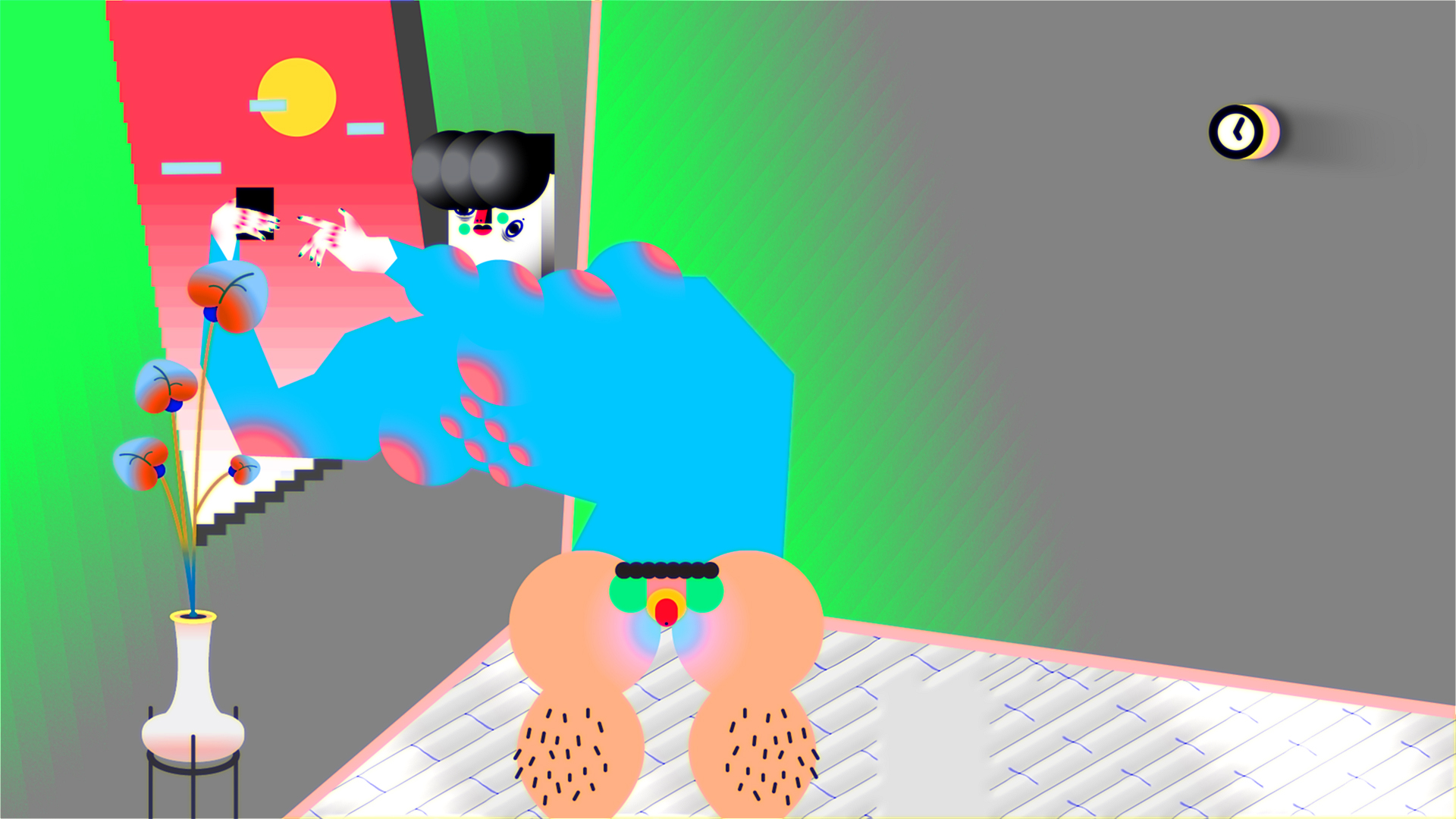

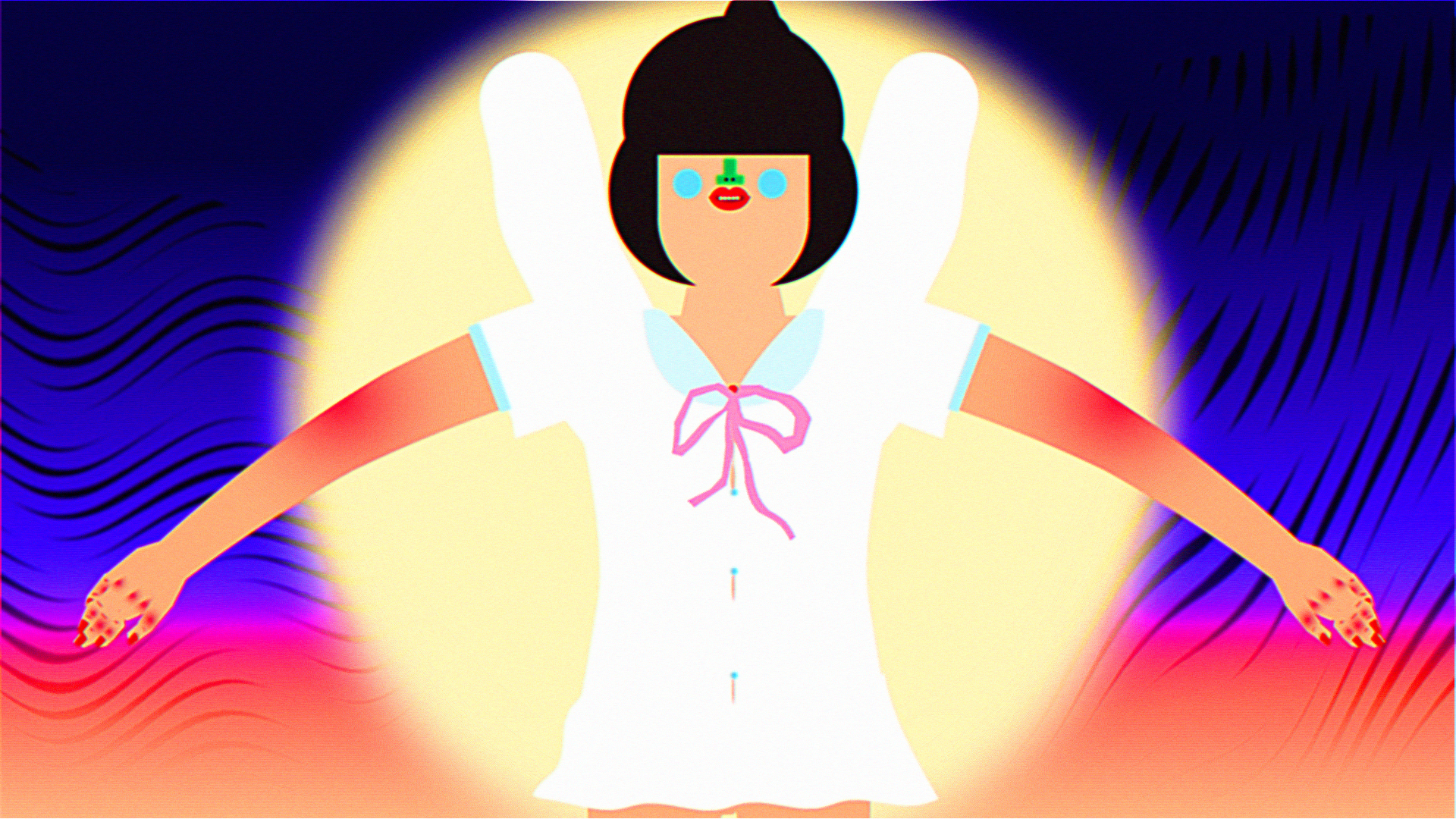

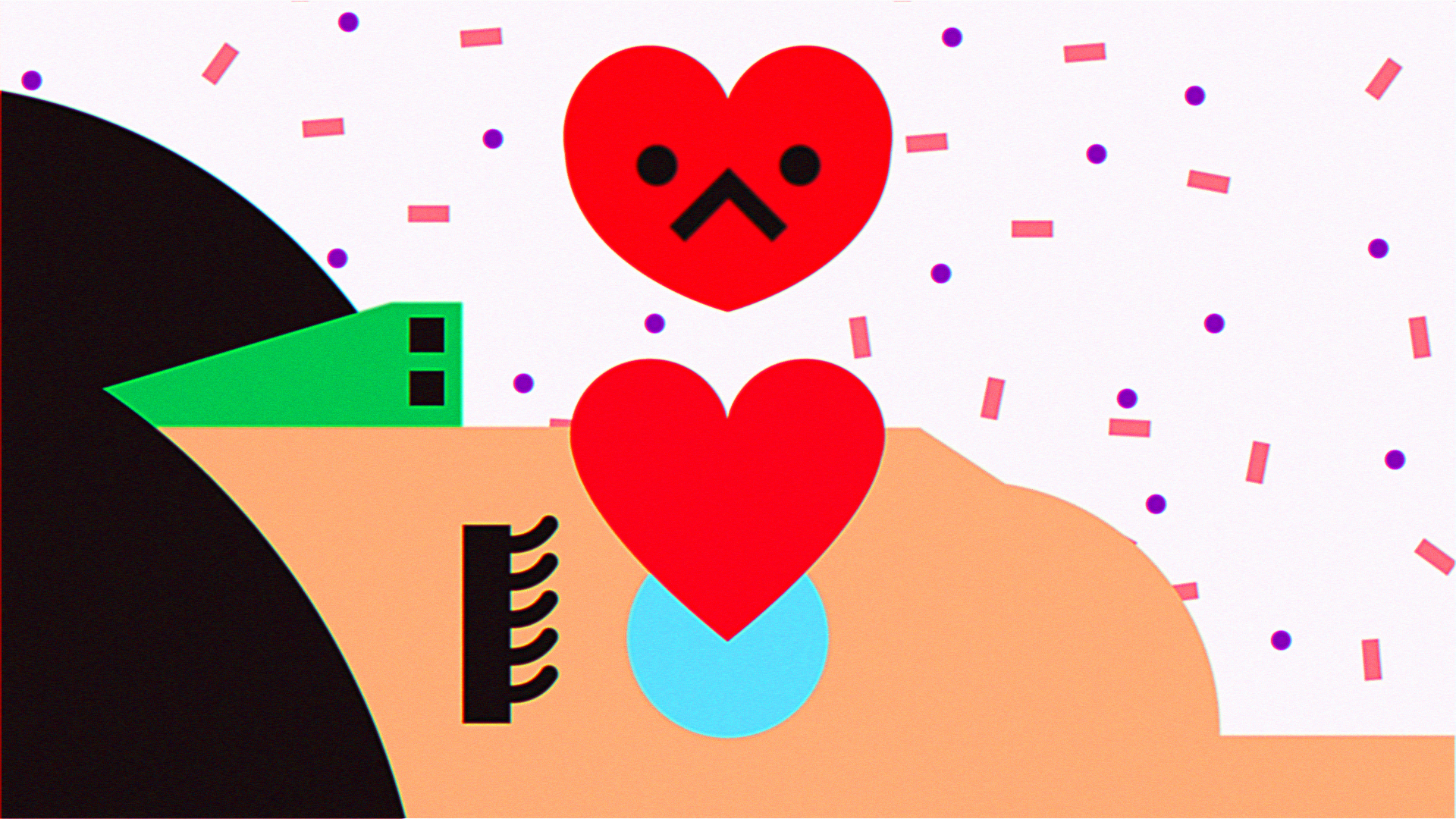

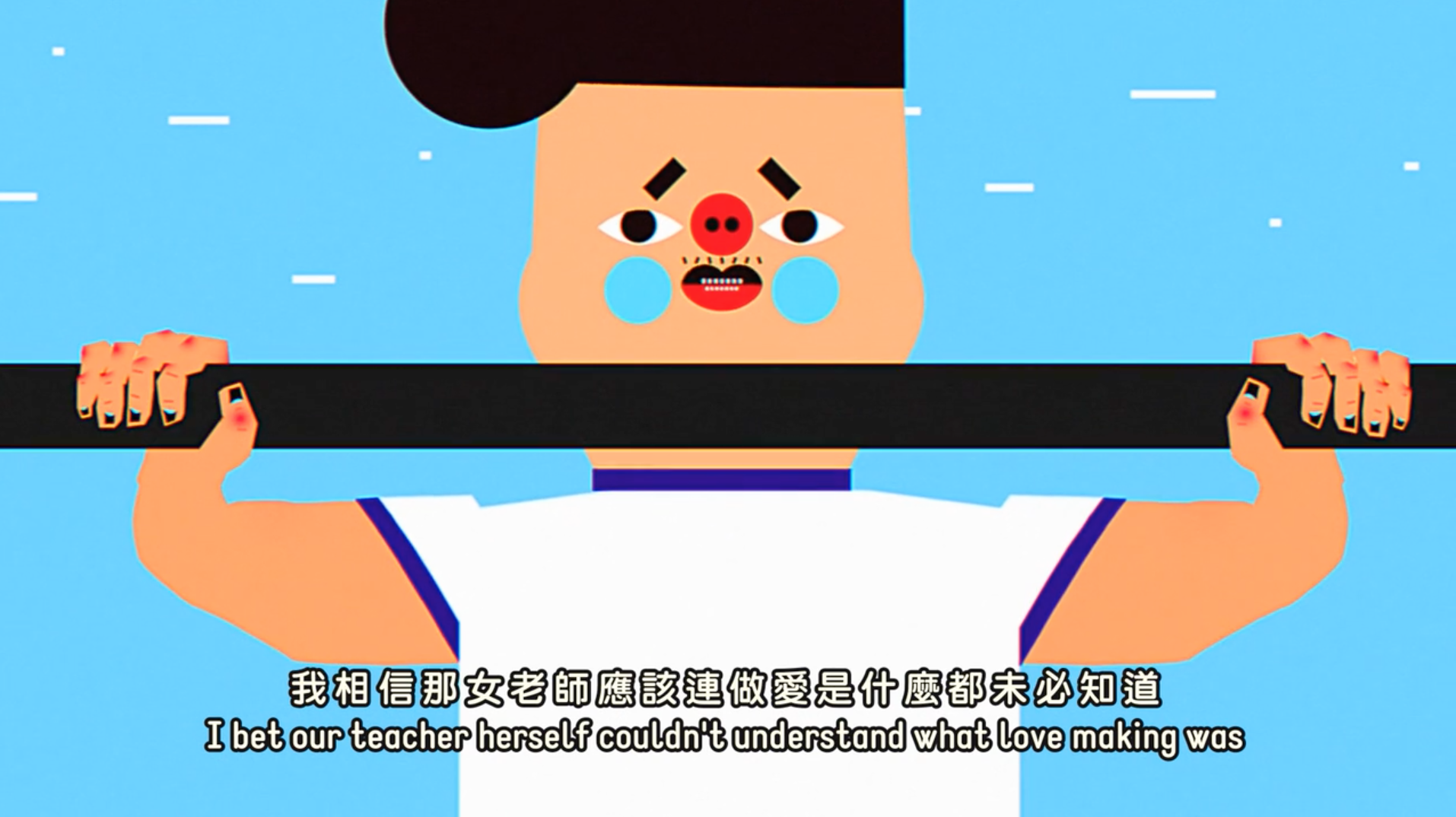

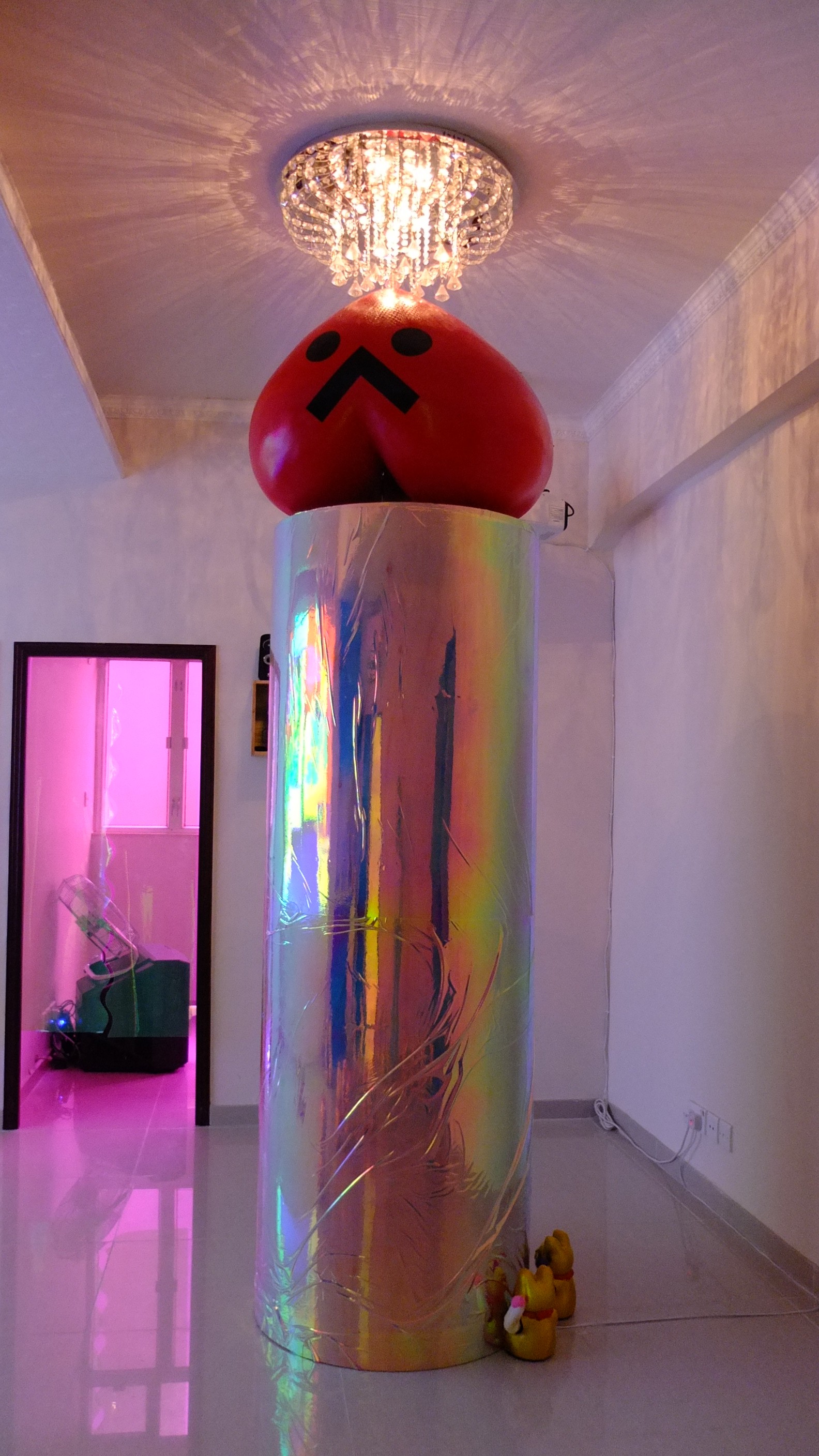

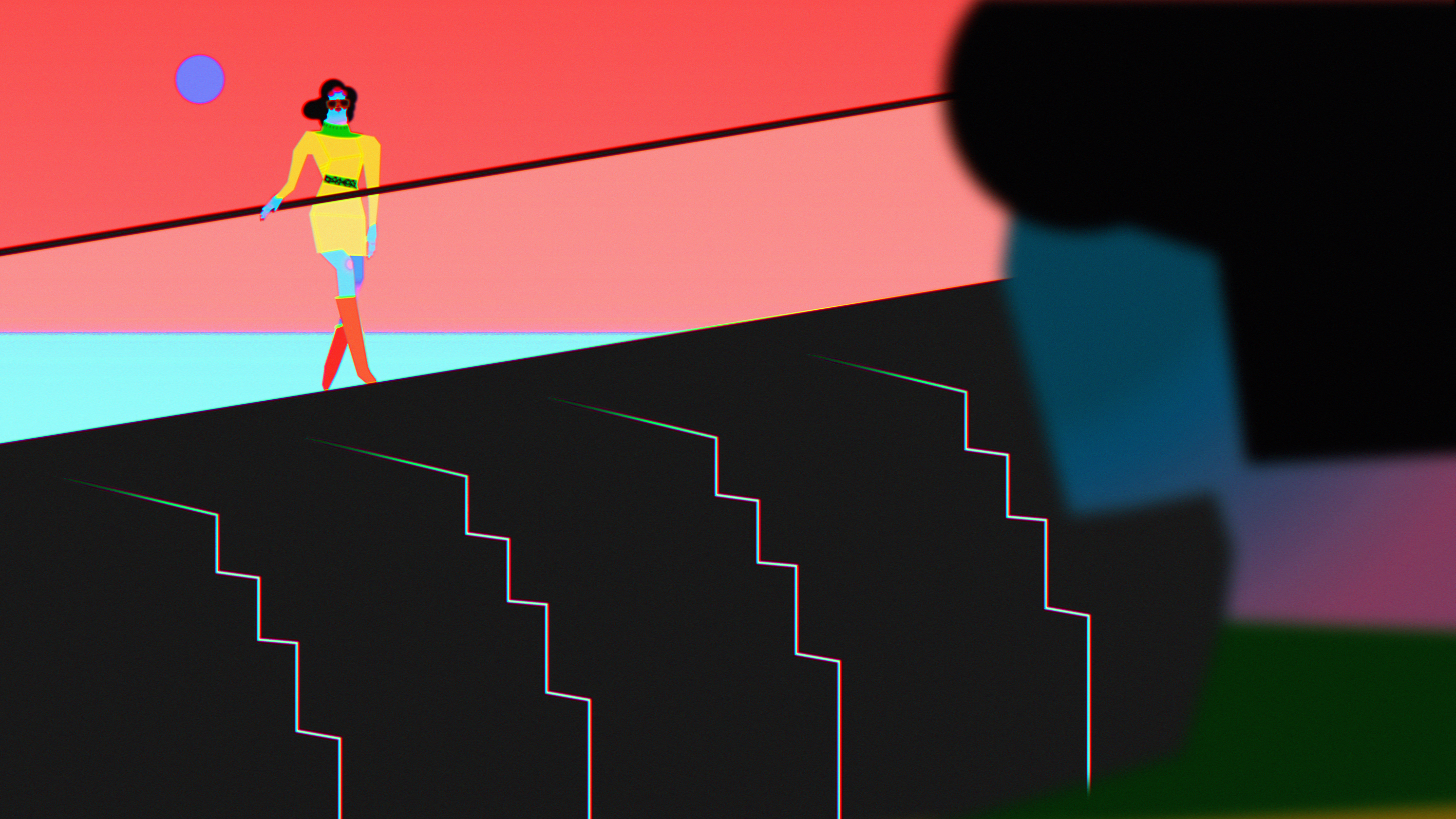

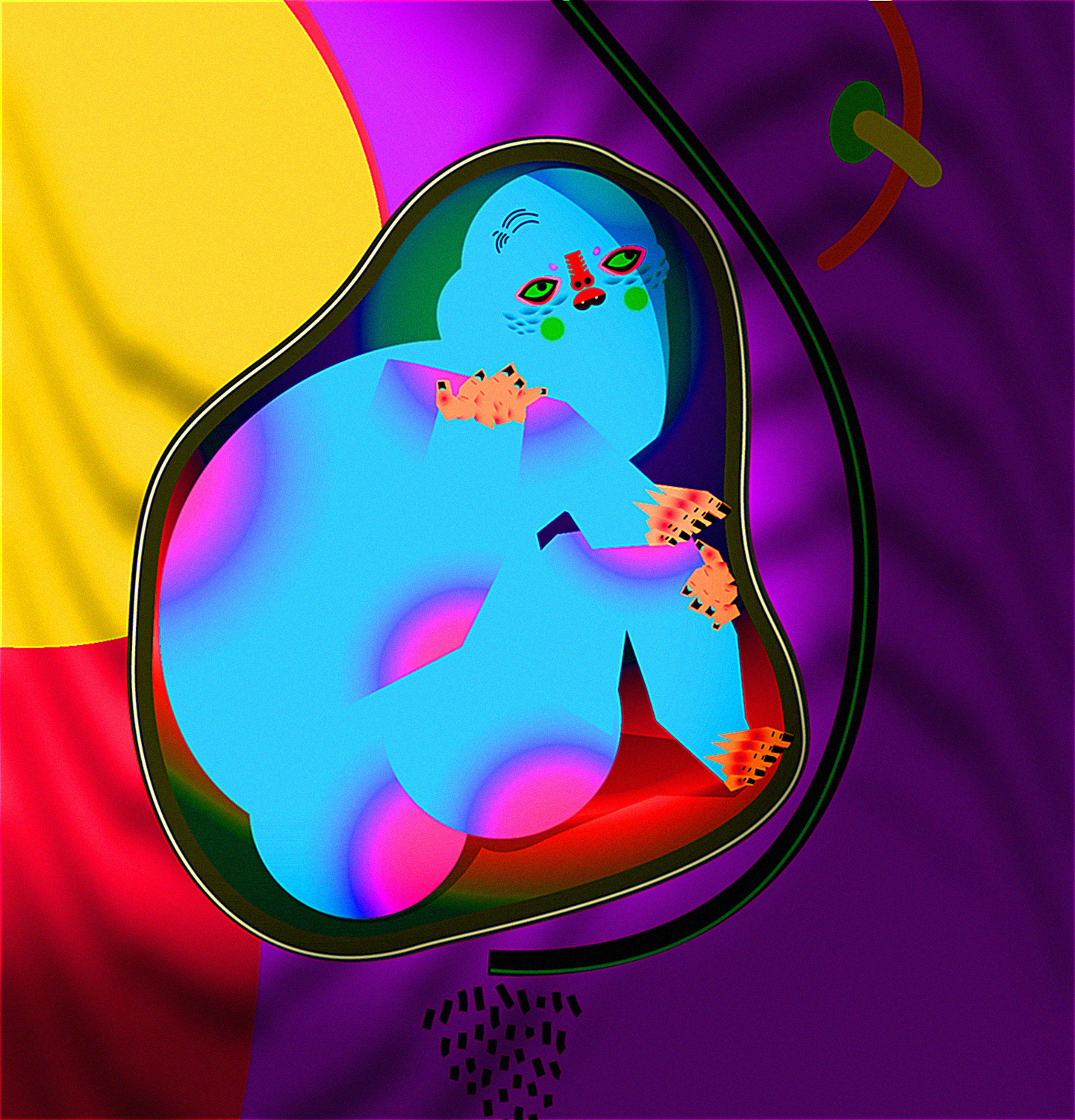

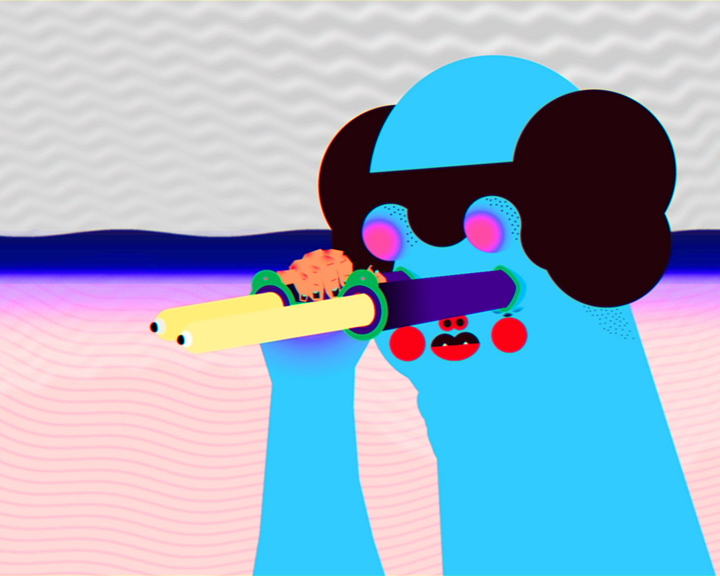

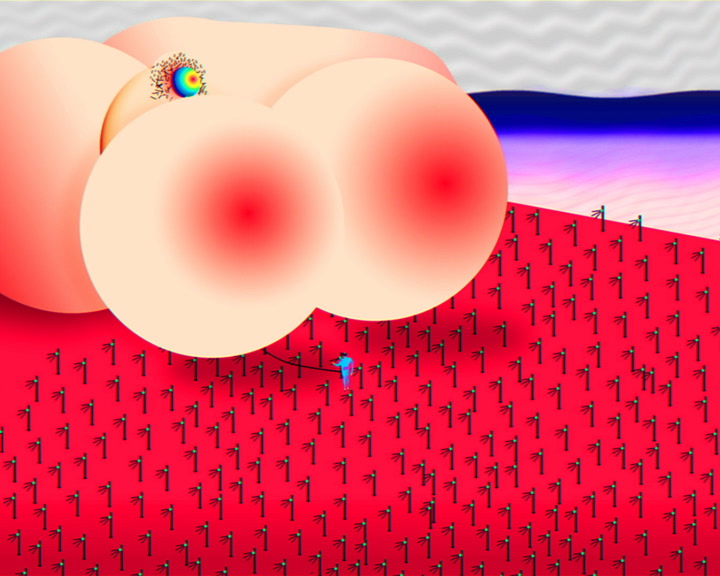

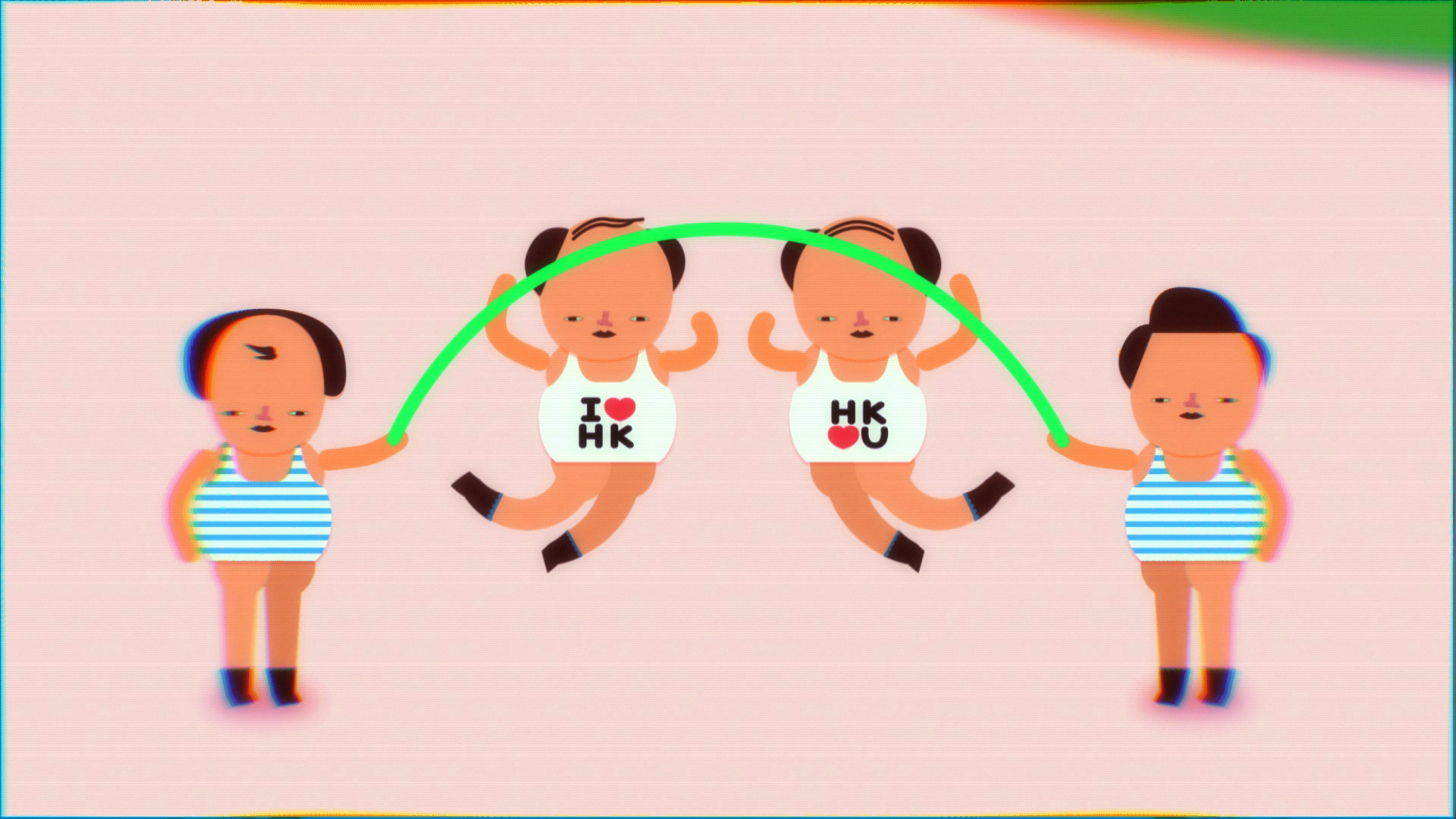

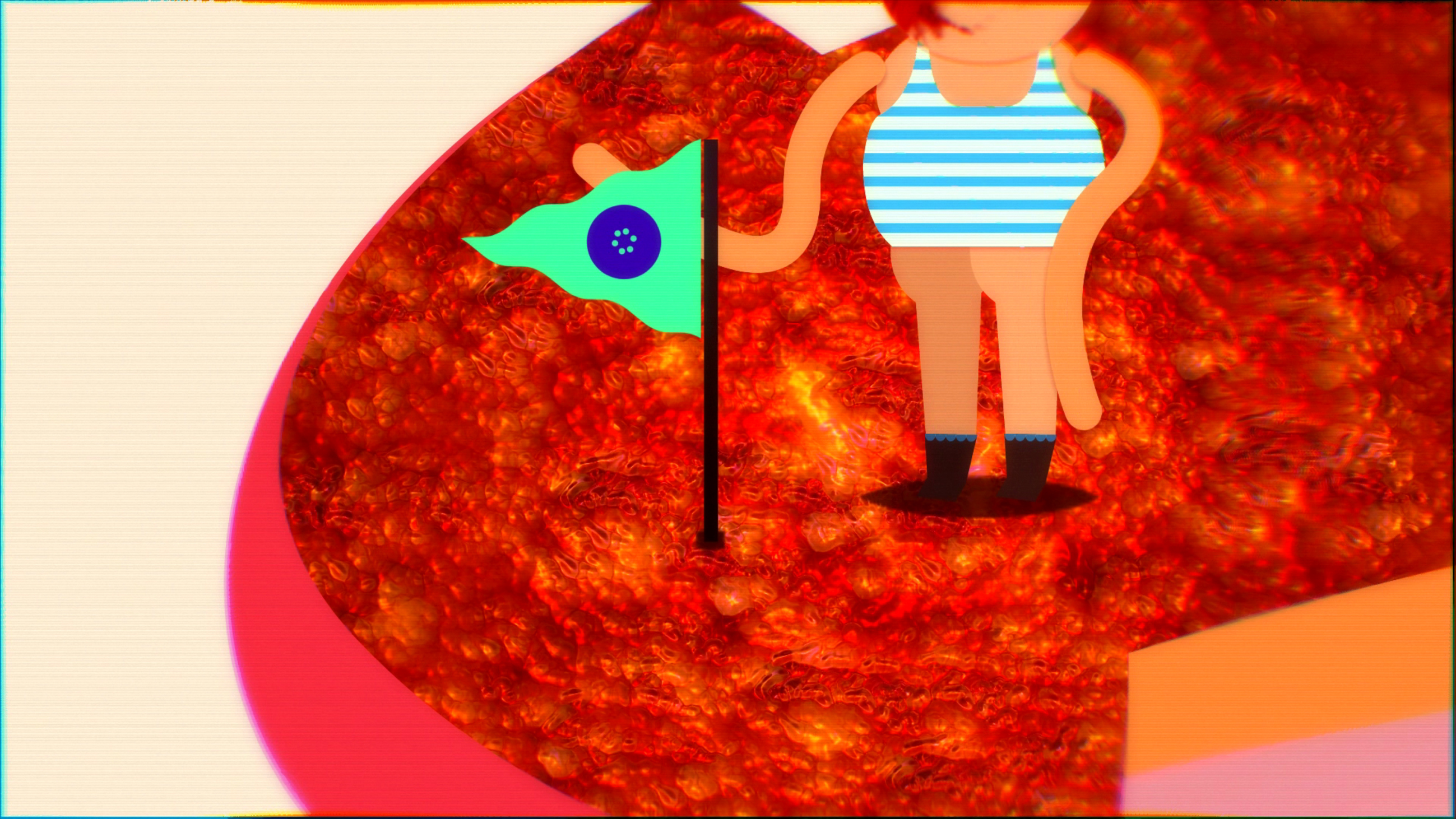

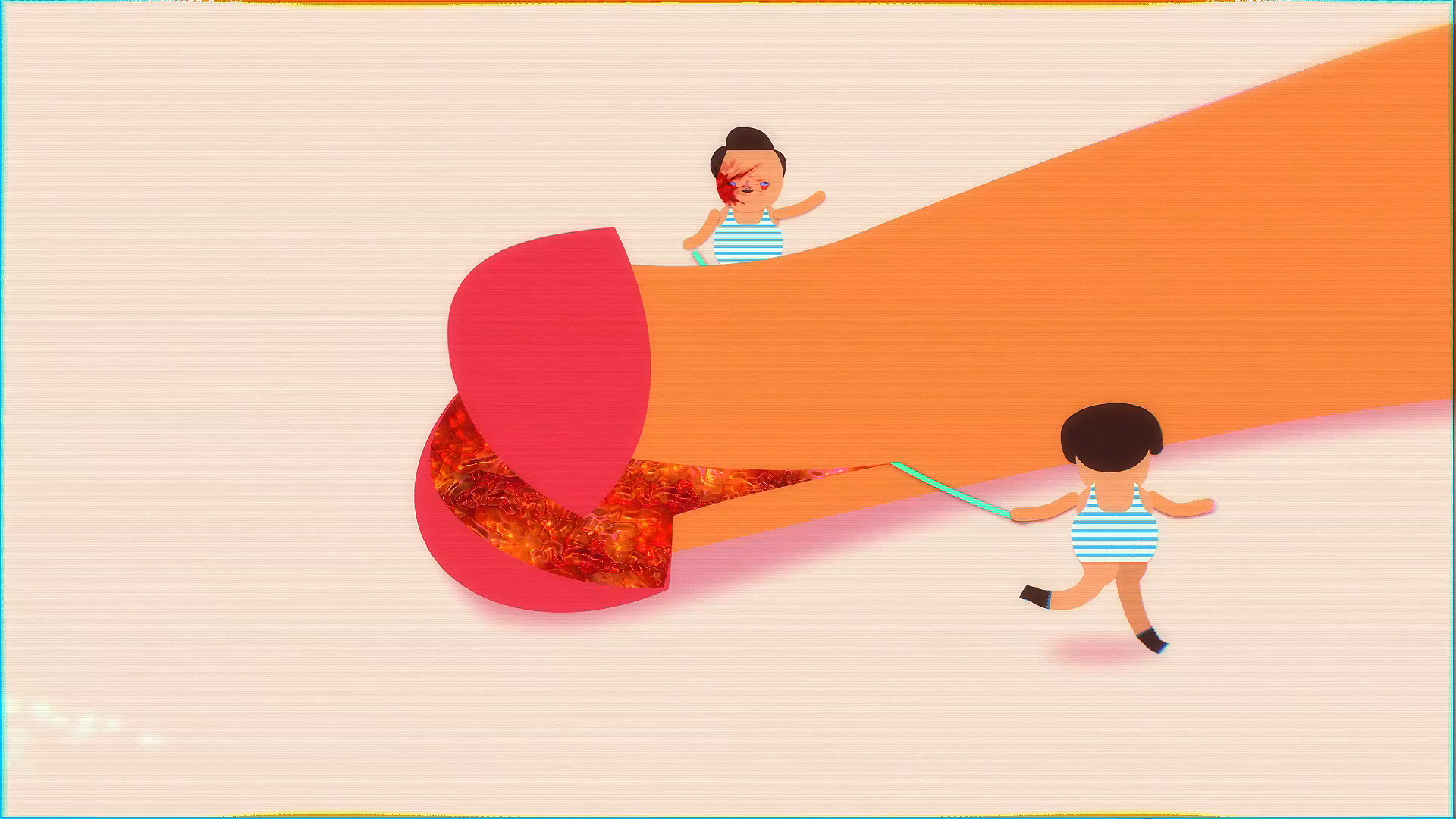

Flashing, pop-like imagery; visual and auditory narrations that explicitly touch upon sex, politics and social relations; vibrant installations that extend into three dimensions the artist’s fantastical animation world – these are but cornerstones of Wong Ping’s practice that combines the crass and the colourful to mount a discourse around repressed sexuality, personal sentiments and political limitations. Hong Kong born and raised, Wong Ping discusses his observations of society, from teenage to adulthood, using a visual language that sits on the border of shocking and amusing.

Running throughout Wong Ping’s animation work is the concept of control or limitation. In a sexual sense, Wong introduces the poles of desire and obsession – animating, illustrating and describing acts or scenarios that are brutally honest, or indeed, compose our personal, ‘evil’ shame. In ‘Doggy Love’ (2015), for example, Ping tells the story of a repressed male teenager who becomes crazy about a girl who has breasts on her back. The animation follows his incapacity to control himself sexually till they fall in love and he ultimately understands the concept of the heart. On the opposite side, ‘Jungle of Desire’ (2015) follows a grown man’s self-loathing as he is incapable to fulfill his wife sexually, and who ultimately succumbs to at-home prostitution and is taken advantage of by a cop. Depressed and incapable, he speaks of taking to the hills and indeed his own life. Herein one starts to understand that despite the flashing, bright-coloured imagery, there lies a darker undertone to Wong’s animation. ‘The Other Side’ (2015), commissioned by M+, is a two-channel installation that uses the story of a man’s reluctant birth, key junctures in his life, and his attempt to reenter his mother’s womb, as a metaphor for the process of immigration.

Indeed, beyond the film’s pop-like appearance, the animation seems to reflect on the changing status quo of Hong Kong and to present a somewhat dystopian outlook. Such humour laced with weariness is also found in further films such as ‘An Emo Nose’ (2016) that tells the story of a man’s heart-shaped nose that moves away in distance from his face with every negative thought. Akin to Pinocchio’s ‘lying nose’, the man starts off as one with his friend: socialising, enjoying the small things in life from watching movies to meeting women. The nose moves away, however, with every damaging thought till the point where the narrator can no longer see it, just vicarouly smells and thereby ‘lives’ through it, leaving him behind to be a social outcast or ‘emo’.

Ultimately, however, Wong’s animations are not meant to be discouraging. They are happy, in a twisted yet realistic way, despite their fantastical scenarios and appearances. They also provide through their rawness a sense of comfort in that even our deepest and most private sentiments or acts are shared by others. In this way, Wong’s work is liberating – a cathartic twist on the trials rooted in daily life.

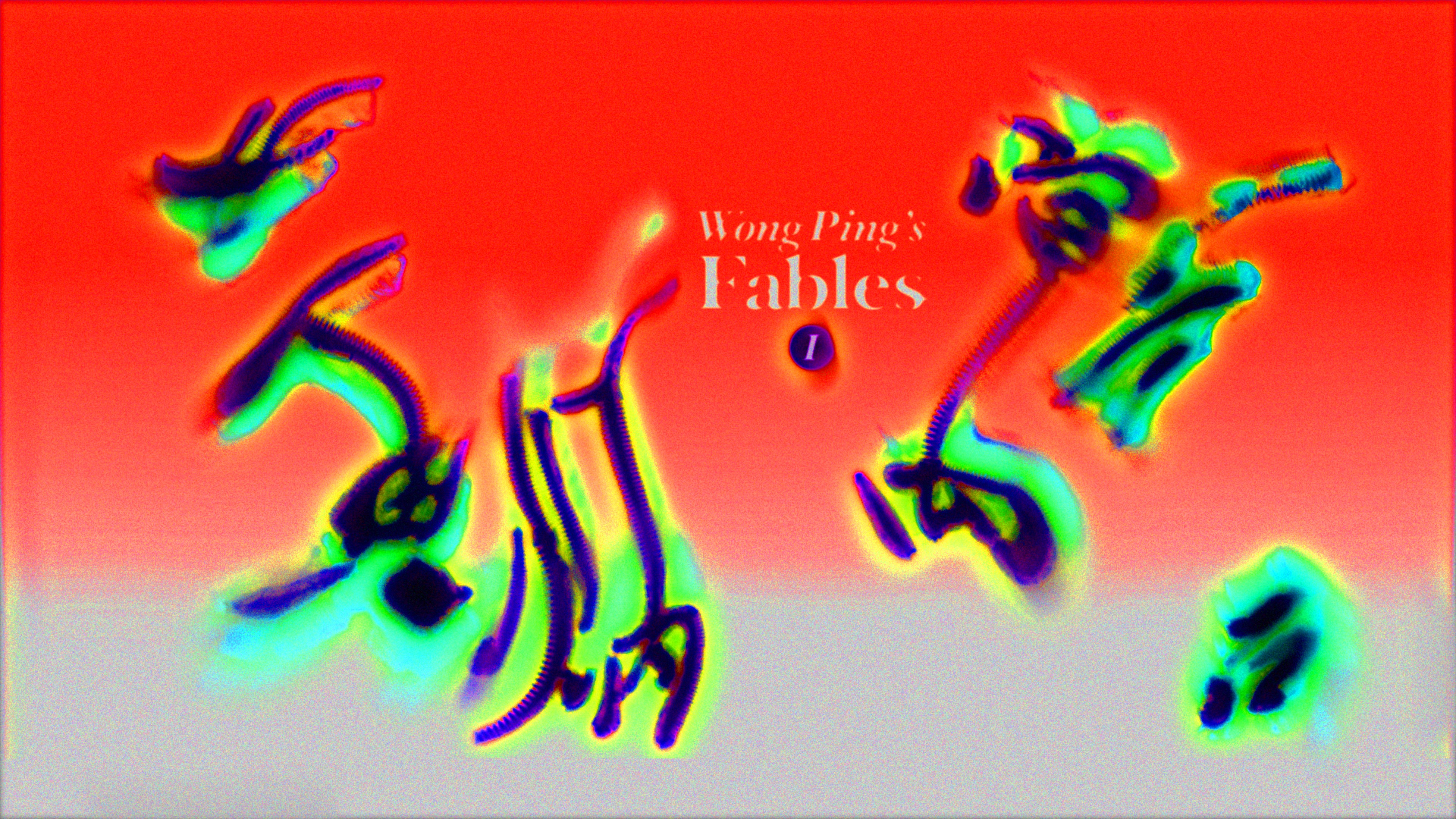

As one of Hong Kong’s most exciting emerging artists, Wong Ping has been commissioned to create works by significant institutions including New Museum, ICA Miami, Kunsthalle Basel, Guggenheim, M+ and NOWNESS. He was shortlisted for M+ Sigg Prize 2025 and awarded Camden Arts Centre Emerging Arts Prize at Frieze, Huayu Youth Award Jury Prize, Young Artist Award by Hong Kong Arts Development Awards and more. He has held solo exhibitions and screenings at major institutions including New Museum, Centre Pompidou, ICA Miami, Camden Arts Centre, Kunsthalle Basel; and participated significant exhibitions internationally at MUDAM Luxembourg, OGR Torino, Guggenheim Museum, New Museum Triennial, Ural Industrial Biennial, amongst others. Wong’s work is held in several permanent collections including Centre Pomidou, M+, Hong Kong, KADIST, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, MoCa Busan, amongst others. His animation films have been presented at numerous film festivals worldwide, including the famous Film Festival Rotterdam, Sundance Film Festival, London Short Film Festival, and Kino der Kunst. In 2019, his film ‘Wong Ping’s Fables 1’ was the winner of The Ammodo Tiger Short Competition at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, who gave a special mention to its sequel ‘Wong Ping’s Fables 2’ in the following year.

Wong Ping Hong Kong, B. Hong Kong, China, 1984

Photo by Annabel Preston. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong.

Photo by: Lai Ka Kit and Tsui Lai Wah

Copper ear sculpture, rock ball machines, transparent tube

Installation dimensions variable, copper ear: 330 x 170 x 35 cm

Photo by South Ho.

Bowling ball, man-made hair

20 x 20 cm

Photo by South Ho.

Light bulb, silicone, stainless steel

145cm x 55 x 30 cm

Photo by South Ho.

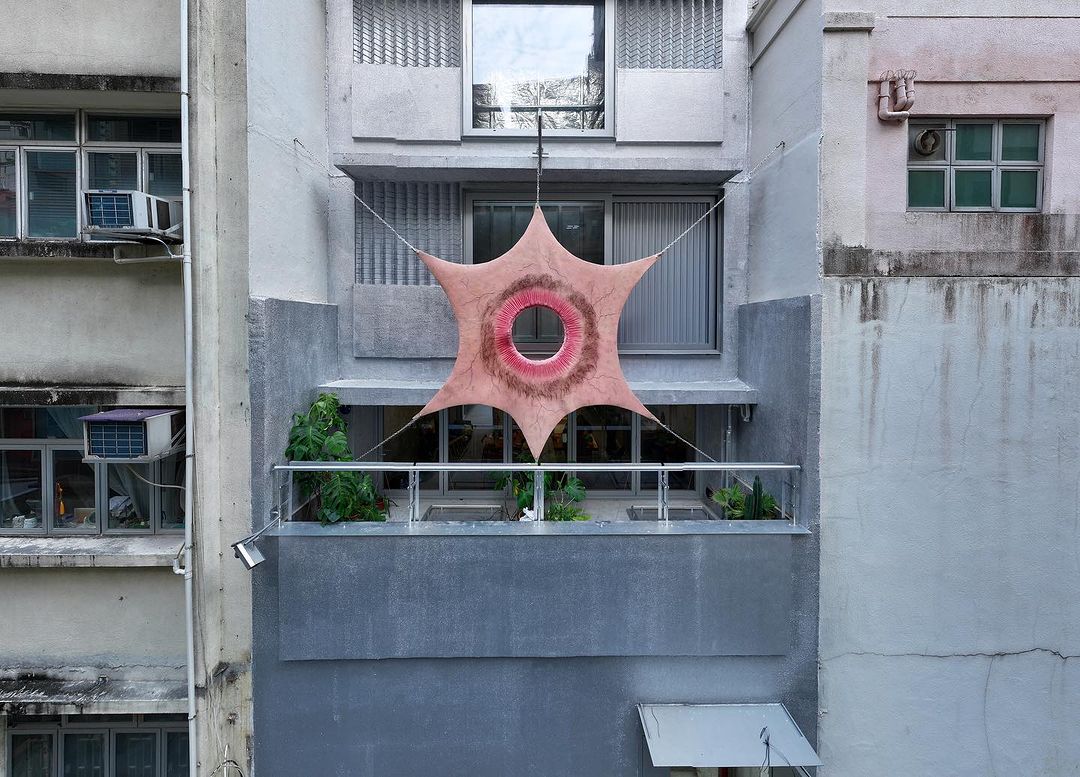

‘anus whisper’, Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2024

Photo by South Ho.

Archival ink print on Hahnemühle Bright White paper

60 x 40 cm

Photo by South Ho.

Three-channel video installation, 1:1 and 16:9, colour, stereo sound

13 min

Photo by South Ho.

Video installation, 1:1, colour, silicone mono speakers

17 min

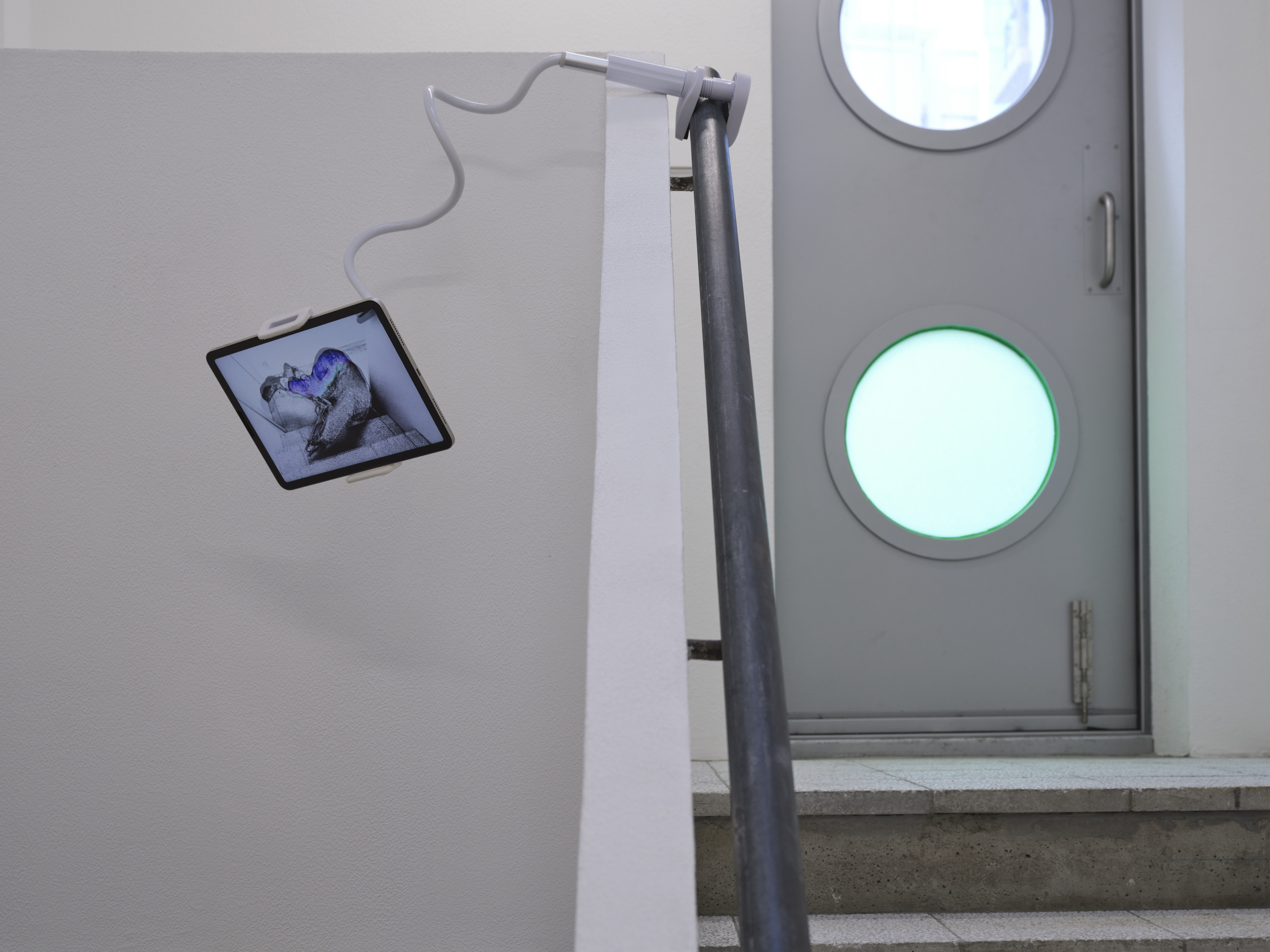

Photo by South Ho.

Video installation, 1:1, colour, silicone mono speakers

17 min

Photo by South Ho.

Video installation, 1:1, colour, silicone mono speakers

17 min

Photo by South Ho.

Bowling ball, man-made hair

20 cm x 20 cm

Photo by South Ho.

Archival ink print on Hahnemühle Bright White paper

40 x 60 cm

Photo by South Ho.

Single-channel HD video, colour, with sound

10 min

Photo by South Ho.

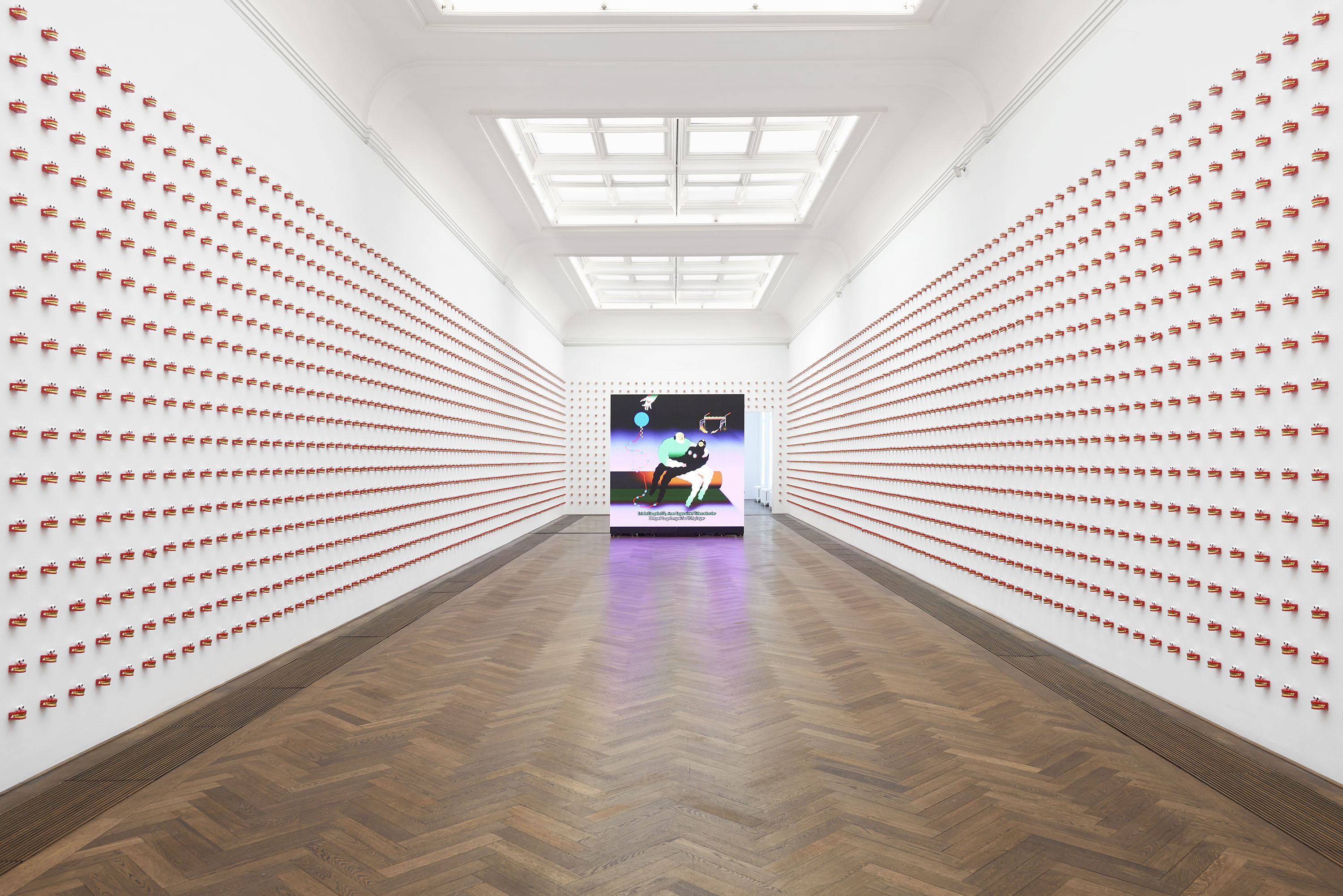

Installation view, ‘edging’, Wong Ping, solo exhibition, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2023.

Image courtesy of the MAK.

Installation view, ‘edging’, Wong Ping, solo exhibition, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2023.

Image courtesy of the MAK.

Installation view, ‘edging’, Wong Ping, solo exhibition, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2023.

Image courtesy of the MAK.

Installation view, ‘edging’, Wong Ping, solo exhibition, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2023.

Image courtesy of the MAK.

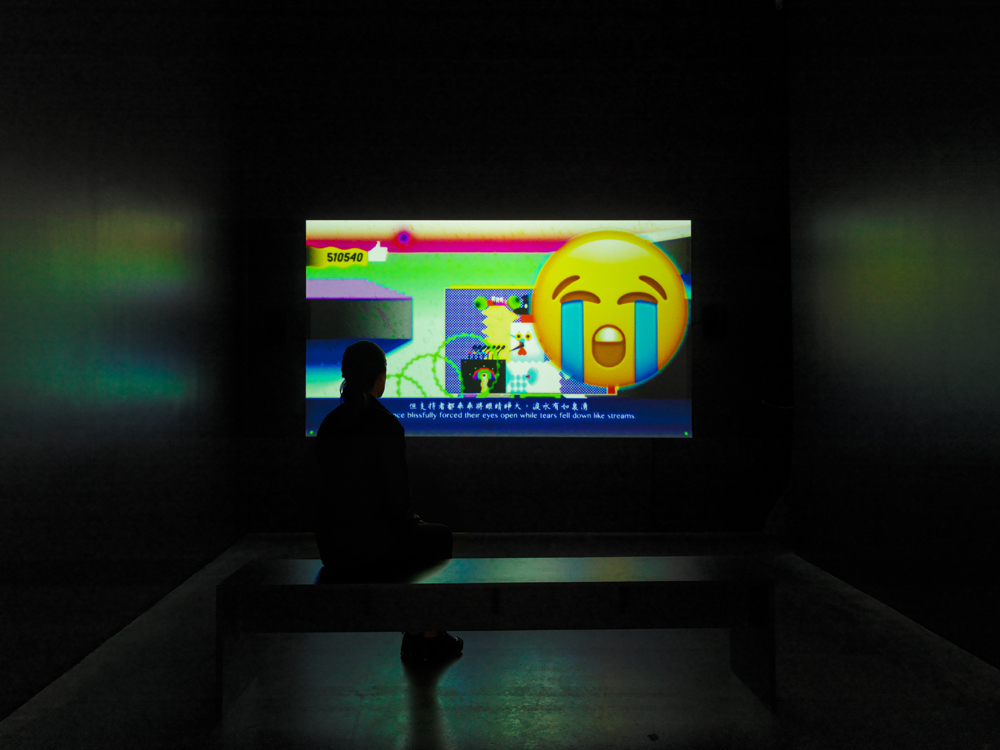

Installation view, Keep Calm and Give a Shit, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), 2023.

Image courtesy of SeMA.

Installation view, Keep Calm and Give a Shit, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), 2023.

Image courtesy of SeMA.

Installation view, Keep Calm and Give a Shit, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), 2023.

Image courtesy of SeMA.

Installation view, Moving Image Media Art (MIMA) program, Sunset Boulevard, West Hollywood, USA.

Courtesy the artist and City of West Hollywood/ Jon Viscott.

Installation view, Moving Image Media Art (MIMA) program, Sunset Boulevard, West Hollywood, USA.

Courtesy the artist and City of West Hollywood/ Jon Viscott.

Installation view, Moving Image Media Art (MIMA) program, Sunset Boulevard, West Hollywood, USA.

Courtesy the artist and City of West Hollywood/ Jon Viscott.

Installation view, Moving Image Media Art (MIMA) program, Sunset Boulevard, West Hollywood, USA.

Courtesy the artist and City of West Hollywood/ Jon Viscott.

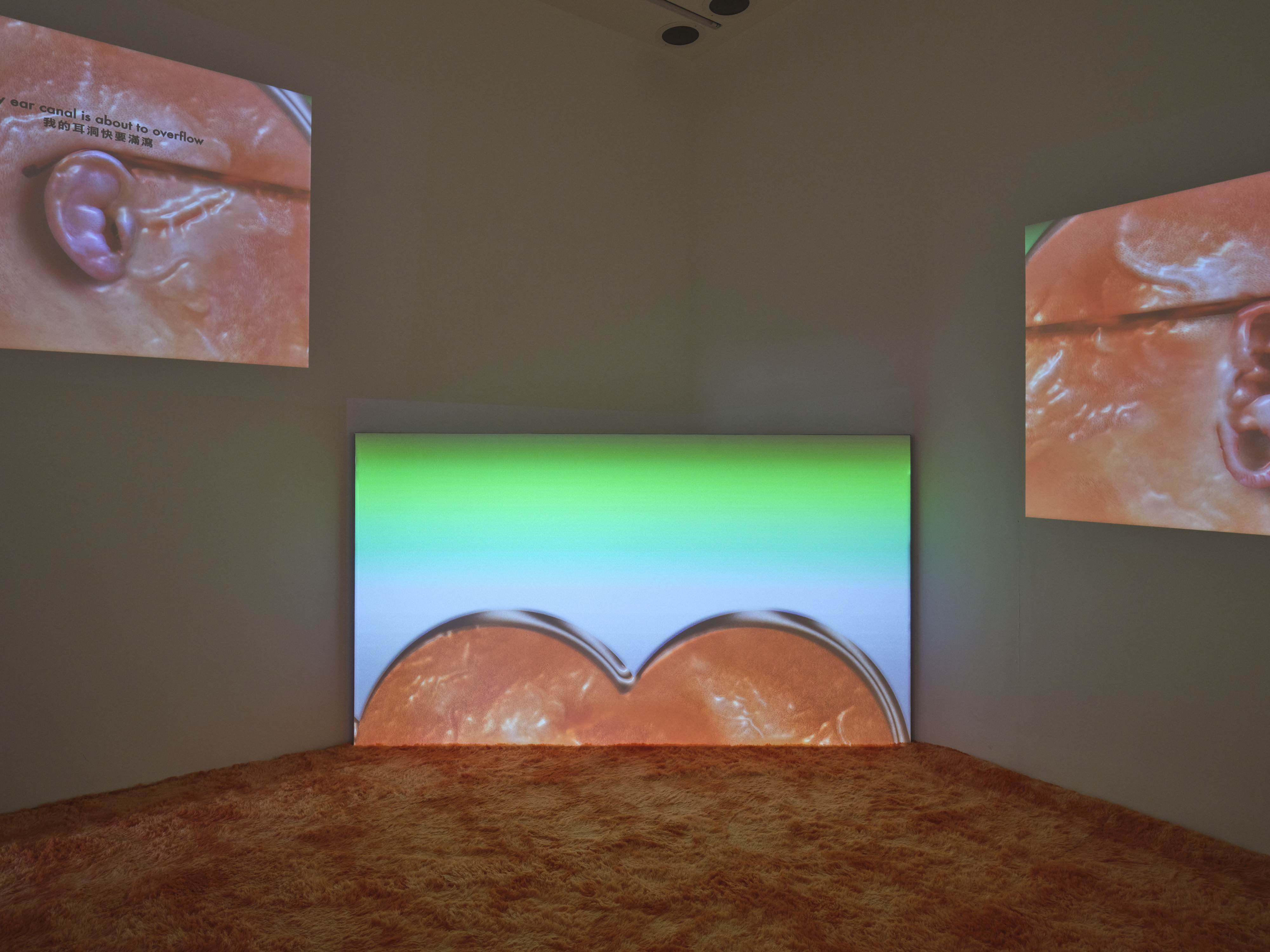

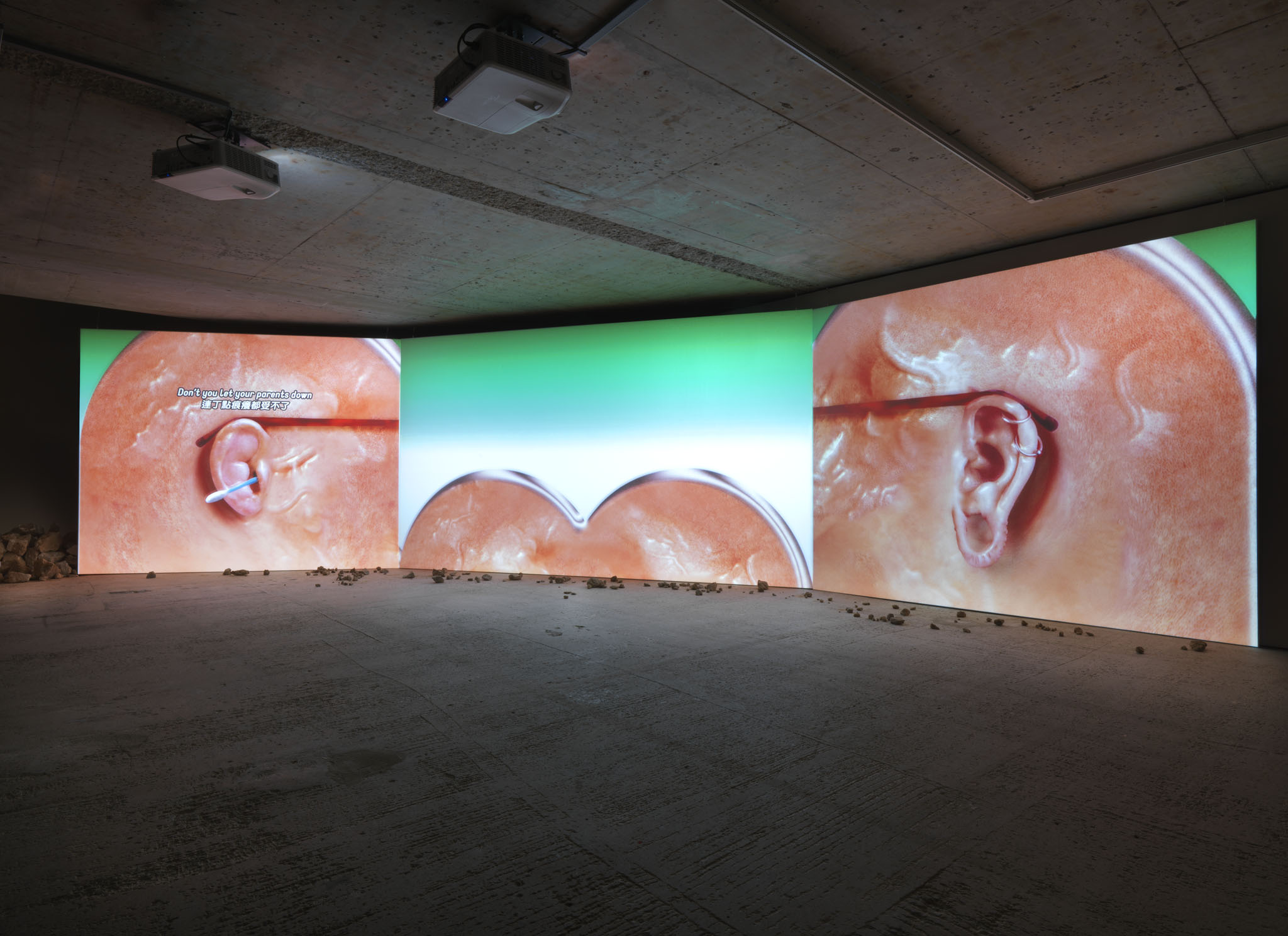

“Earwax”, Times Art Center Berlin, 2022.Commissioned by Times Art Center Berlin. © Wong Ping. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

“Earwax”, Times Art Center Berlin, 2022.Commissioned by Times Art Center Berlin. © Wong Ping. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

“Earwax”, Times Art Center Berlin, 2022.Commissioned by Times Art Center Berlin. © Wong Ping. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

“Wong Ping: Your Silent Neighbor”, New Museum, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of New Museum. photographer: Dario Lasagni

“Wong Ping: Your Silent Neighbor”, New Museum, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of New Museum. photographer: Dario Lasagni

“Wong Ping: Your Silent Neighbor”, New Museum, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of New Museum. photographer: Dario Lasagni

“Wong Ping: Your Silent Neighbor”, New Museum, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of New Museum. photographer: Dario Lasagni

“Wong Ping: Your Silent Neighbor”, New Museum, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of New Museum. photographer: Dario Lasagni

Site-specific installation, 180 × 180 × 250 cm.

Commission by UCCA Edge, courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery. Image courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

“Wong Ping: The Great Tantalizer”, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Photo by Pierre Le Hors

“Wong Ping: The Great Tantalizer”, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, 2021.

Image courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Photo by Pierre Le Hors

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Dec 3 2019 – Apr 26, 2020

Photo by Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Image courtesy of the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Dec 3 2019 – Apr 26, 2020

Photo by Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Image courtesy of the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Dec 3 2019 – Apr 26, 2020

Photo by Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Image courtesy of the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Dec 3 2019 – Apr 26, 2020

Photo by Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Image courtesy of the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

‘Dear, Can I Give You a Hand?’, 2018, film, and ‘The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetry Limited’, 2019, toy dentures from Wong Ping: Heart Digger, Camden Arts Centre, 2019

© Wong Ping

Photographer Luke Walker

‘Dear, Can I Give You a Hand?’, 2018, film, and ‘The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetry Limited’, 2019, toy dentures from Wong Ping: Heart Digger, Camden Arts Centre, 2019

© Wong Ping

Photographer Luke Walker

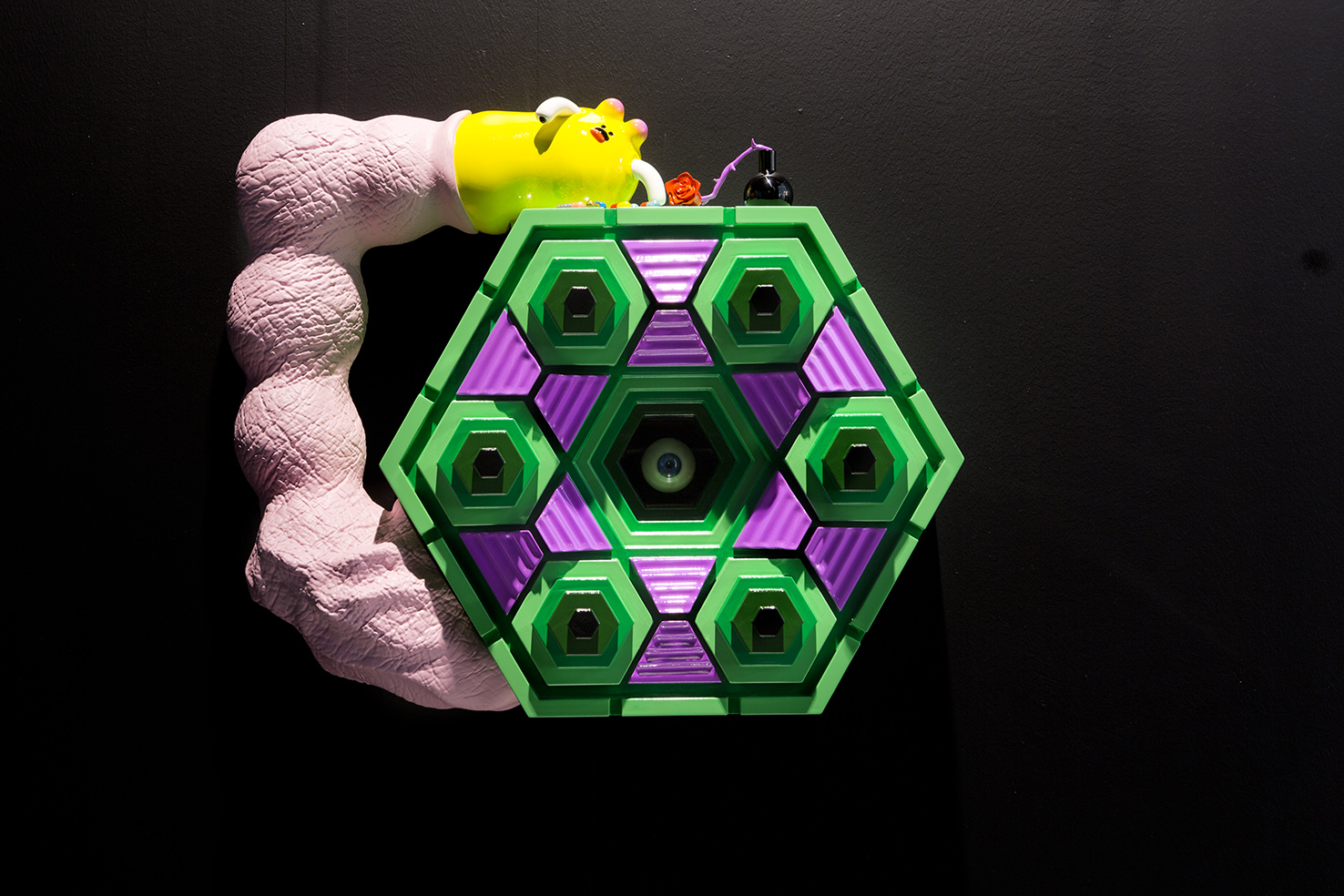

‘Organic Smuggling Tunnel (Chunk 1)’, 2019 from Wong Ping: Heart Digger, Camden Arts Centre, 2019

© Wong Ping, courtesy Edouard Malingue Gallery

Photographer Luke Walker

‘Organic Smuggling Tunnel (Chunk 1)’, 2019 from Wong Ping: Heart Digger, Camden Arts Centre, 2019

© Wong Ping, courtesy Edouard Malingue Gallery

Photographer Luke Walker

‘Organic Smuggling Tunnel (Chunk 2)’, 2019 from ‘Wong Ping: Heart Digger’, Camden Arts Centre at Cork Street, 2019

© Wong Ping, courtesy Edouard Malingue Gallery

Photographer: Luke Walker

‘Wong Ping: Heart Digger’, Camden Arts Centre at Cork Street, 2019

© Wong Ping, courtesy Edouard Malingue Gallery

Photographer: Luke Walker

‘Dear, can I give you a hand?’

2018

Kunsthalle Basel, 2019

Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

‘Dear, can I give you a hand?’

2018

Kunsthalle Basel, 2019

Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

‘The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery Limited’

2019

Kunsthalle Basel, 2019

Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

‘Bestiality rider A’

2019

Kunsthalle Basel, 2019

Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Edouard Malingue Gallery at Frieze London, 2018

3D printed relief painting

55 x 47 x 20.5 cm

3D printed relief painting

40 x 66 x 17.5 cm

3D printed relief painting

40 x 62 x 14 cm

3D printed relief painting

50 x 64 x 12 cm

3D printed relief painting

41 x 38 x 17 cm

3D printed relief painting

40 x 27 x 18 cm

2018

Animated LED color video installation, with sound

Dimensions variable

‘One Hand Clapping’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2018

Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald

‘One Hand Clapping’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2018

Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald

‘One Hand Clapping’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2018

Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald

‘One Hand Clapping’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2018

Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald

2018 Triennial: “Songs for Sabotage”, New Museum, New York

Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

2018 Triennial: “Songs for Sabotage”, New Museum, New York

Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

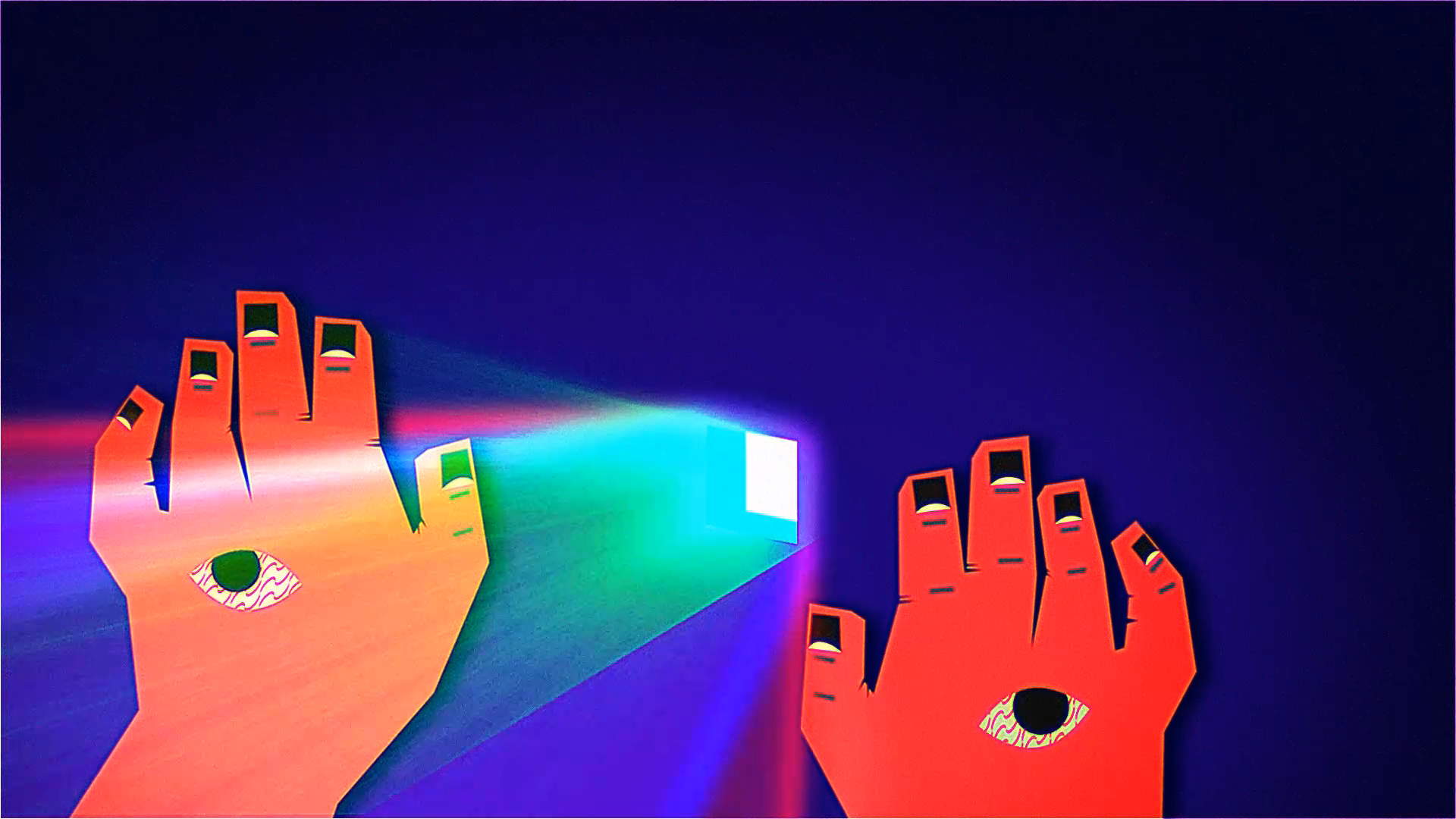

2018

Single channel animation

13 min

Image courtesy of the artist

2018

Single channel animation

13 min

Image courtesy of the artist

2018

Single channel animation

13 min

Image courtesy of the artist

2018

Single channel animation

13 min

Image courtesy of the artist

‘Who’s the Daddy’ at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

2017

‘Who’s the Daddy’ at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

2017

‘Who’s the Daddy’ at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

2017

‘Who’s the Daddy’ at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

2017

‘Who’s the Daddy’ at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

2017

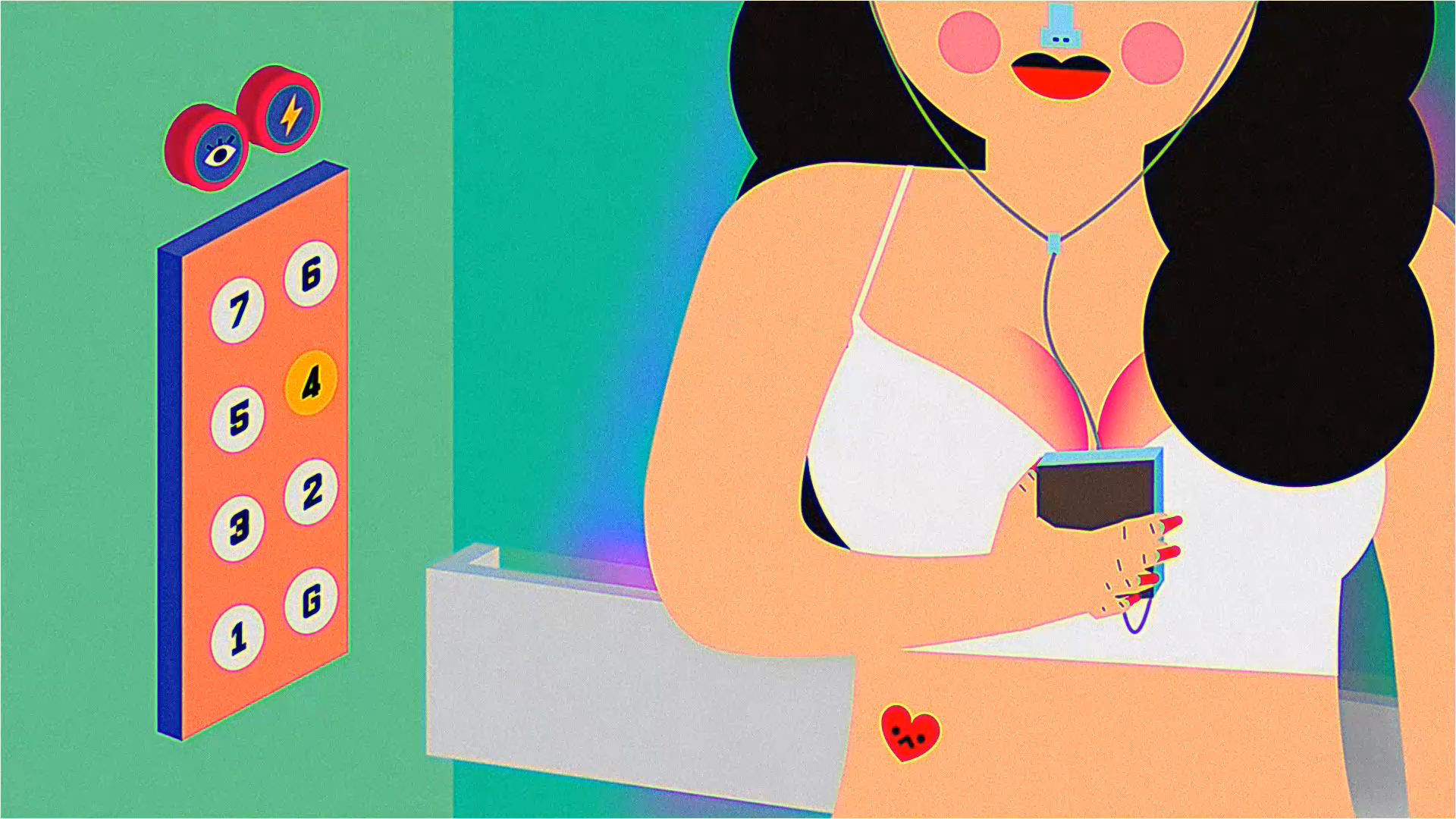

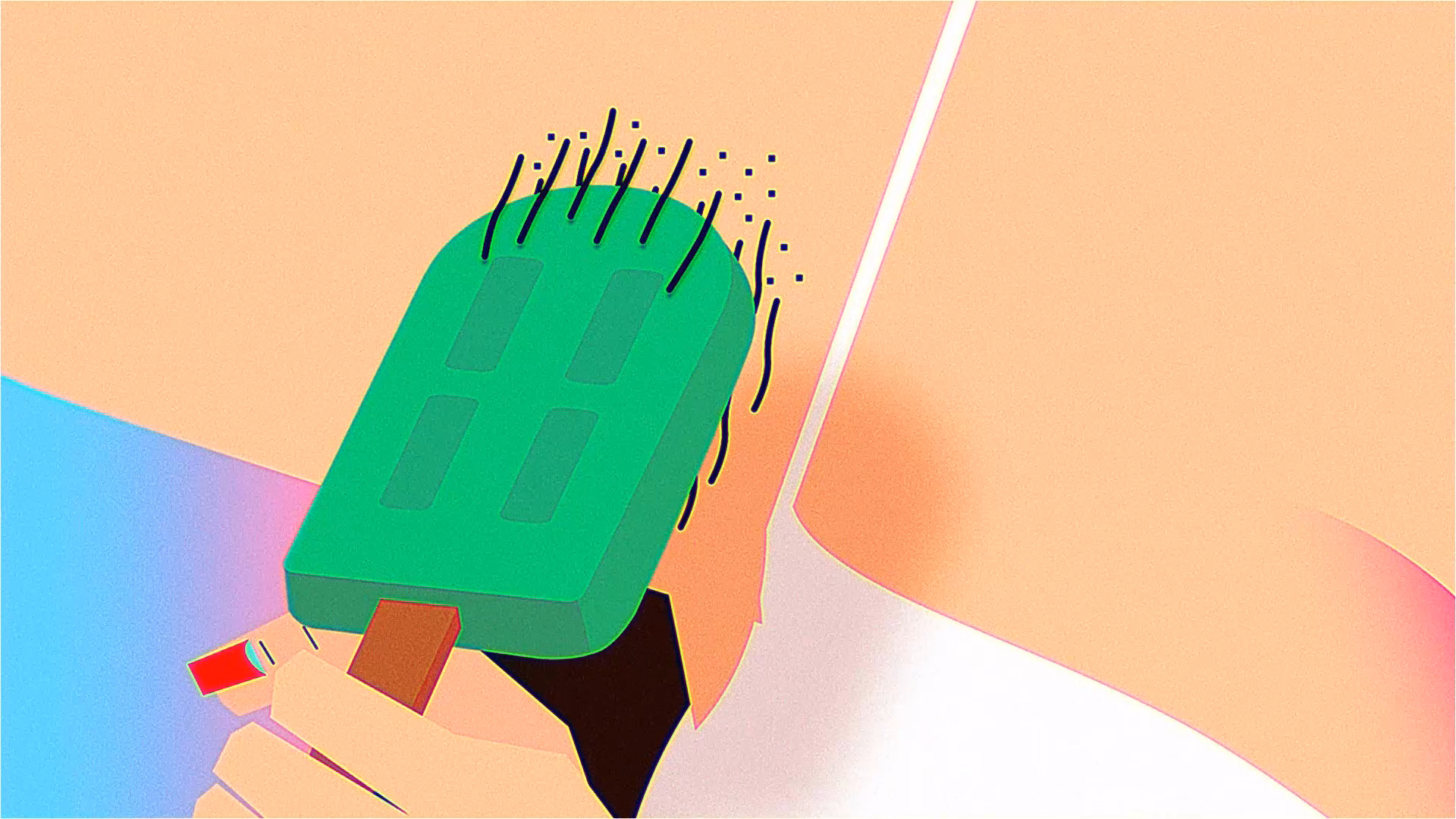

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

2017

Single-channel animation

9 min

Installation view at Art Basel Miami Beach 2016

Installation view at Art Basel Miami Beach 2016

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

5 min 59 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

4 min 23 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

6 min 50 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

28 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

28 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

28 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

28 sec

2015

Single-channel video animation

28 sec

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2015

Two-channels video animation

8 min

2014

Eight-channels video animation

5 min

2014

Eight-channels video animation

5 min

2014

Eight-channels video animation

5 min

2014

Single-channel video animation

3 min 48 sec

2014

Single-channel video animation

3 min 48 sec

2014

Single-channel video animation

3 min 48 sec

2014

Single-channel video animation

3 min 48 sec

2014

Single-channel video animation

3 min 48 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2013

Single-channel video animation

2 min 40 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-Under the Lion CrotchUnder the Lion Crotchchannel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec

2011

Single-channel video animation

4 min 38 sec