When you hold the world

In your trembling hand

You’d think you’d hear a choir sing

It’s a quiet thing

—Morgana King, It’s a quiet thing

Suddenly, the system we had sketched closes. In the nesting series of vampires, the first, as if by luck, jumps to

the last position and, in one fell swoop, eliminates the intermediates, who leave in a hurry. A good bit of

feedback, like a slap on the cheek to get rid of a mosquito: destructions and flattenings of the system. It was

nothing or almost nothing.

—Michel Serres, The Parasite

Kiang Malingue is pleased to present at its Sik On street space It’s a quiet thing, Lai Chih-Sheng’s exhibition that directly negotiates with the architecture of the space. By presenting a series of site-specific installations and interventions, the exhibition in its totality examines Kiang Malingue’s headquarters opened in the second half of 2022, configuring an environment that is ephemeral and poetic. It emphasises the confrontational relationship between the actor, the observer and the architecture, while reflecting upon the physical and ideological limitations and potentials of an exhibition. Lai freely applies a singular perception of space that he has developed over the last three decades, expressing by staging seemingly barren scenes conceptual generosity, in relation to urban, architectural and human conditions today.

Named after Morgana King’s song It’s a quiet thing from the 1960s, the exhibition transforms via a series of spatial interventions the boundary between quietness and noise into the figure of a mosquito: after appropriately conditioning the second floor white cube space, the artist leaves it entirely to the insect. Lai: “Regarding the subtle quietness, the barely noticeable… is there anything hidden in it? One of the most common noises or nuisances in life is probably the discovery of little insects like mosquitos around you. As soon as there is one, people start confronting the air and the space, with their hearing and sight heightened, becoming evermore sensitive. This seemingly feeble threat in a realistic way amplifies our perception of a lived space; we fear that in the blink of an eye the mosquito could have it. Of course, once we are done with it, on the other hand, we get to feel a particularly rewarding satisfaction.”

Instead of confronting an artwork, the observer is left with an isolated mosquito; although the artist’s intervention delineates the relationship between the observer and the observed thing, it is difficult to categorise this observation as appreciation or confrontation. On the contrary, the artist means to explore the possibility of noises and entropic elements, and of being free from them: “Straightforwardly handing over the space. Placing the mosquito next to a blankness, making a whole space — where people are also invited for exactly this purpose — available for its wander. This idea may generate other thoughts regarding exhaustion, waste and meaninglessness, but it is perhaps exactly at this uncertain juncture where something mild and quiet can grow within our feelings, where there is immediately a sense of spiralling, so much so that we start to think about (and for) a mosquito.” The intervention I put a mosquito in the space practises hindering one’s sight with a leaf: the leaf is at once the mosquito and the room in which it resides. Guests on both sides of the screen are reminded of weak dangers: floaters in eyes; a situation in which one is prey; or a standoff in which each individual’s presence is corporeally and spatially experienced.

In It’s a quiet thing, Lai also further investigates the potential of a mosquito as a quasi-object by presenting a new video Daze. In the artist’s view, the societies and art worlds in places such as Hong Kong and Taiwan have been slowed down in recent years due to the pandemic, but are at the same time collectively and paradoxically anticipating accelerated, intense events; a feeble noise such as the presence of a mosquito at once suggests the emergence and memory of a pandemic, and an insistence on the urgency of seemingly mundane, uneventful life — perpetuated noises, nuisances and interruptions contain within themselves revolutionary potentials.

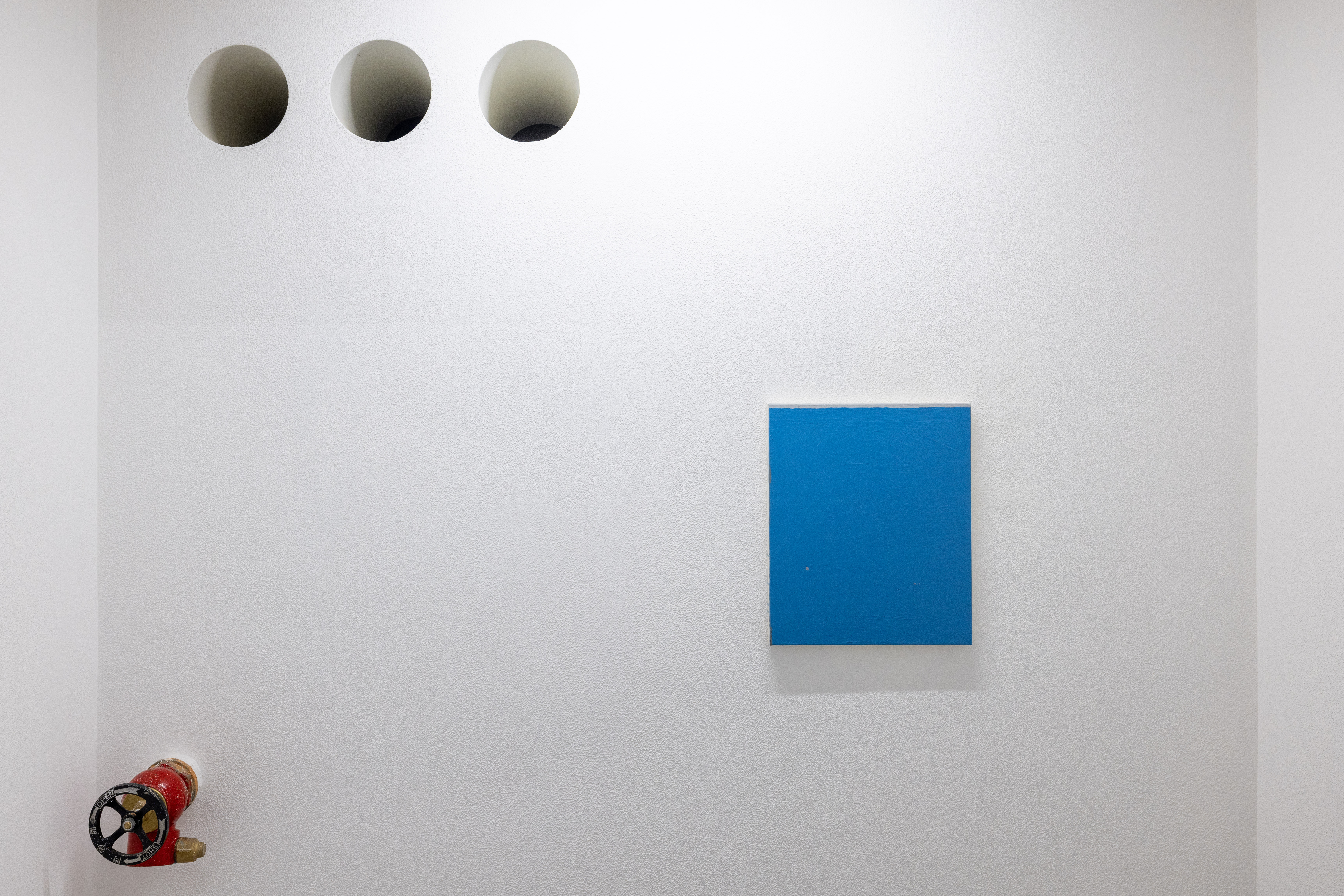

Other site-specific installations in the exhibition include A brick on the parapet, and A brick on the crossbeam, making use of one of the artist’s favourite construction materials that means to question the integrity of an architectural environment; recent creations such as Sunbath, Drawing Paper and Paint Cans on the other hand demonstrates the artist’s intent to de-spectacularize. The installation Princess Pea made specifically for the top floor gallery space continues the artist’s interest in the theme of the land, first manifested in the 1990s: be it the numerous iterations of Border at Aichi Triennale and Biennale de Lyon among other major international exhibitions; Island shown in 2015 at Para Site, Hong Kong; or Redundant, conceived in 2022 for Taipei Dangdai, these works reveal Lai’s long-term concern with the foundation of artistic practice today.

It's a quiet thing Lai Chih-Sheng

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 97 cm

Laundry basket, dress

42 x 31 x 38 cm

Laundry basket, dress

42 x 31 x 38 cm

Marble

30 x 39.8 x 0.5 cm

Marble

30 x 39.8 x 0.5 cm

Marble

30 x 39.8 x 0.5 cm

Signed and dated/numbered (20121117) behind the paper by the artist

Watercolor paper, pencil

Paper: 57.6 x 76.8 cm

Frame: 69 x 87 cm

Signed and dated/numbered (20121117) behind the paper by the artist

Watercolor paper, pencil

Paper: 57.6 x 76.8 cm

Frame: 69 x 87 cm

Signed and dated/numbered (20121117) behind the paper by the artist

Watercolor paper, pencil

Paper: 57.6 x 76.8 cm

Frame: 69 x 87 cm

Pencil, paper

Unframed: 36 x 26 cm

Framed: 45.5 x 35.5 x 4 cm

Single channel video

7’15”

Edition of 3

Single channel video

7’15”

Edition of 3

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 31.5 cm

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Mosquito, screen door, gauze, single channel video

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Bricks, acrylic paint

11.5 x 21.3 x 9.3 cm

Brick, acrylic paint

23 x 11 x 5.6 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.5 x 38 cm

Acrylic paint, paper, plastic

Set of 7, 8 × 8 × 8 cm each

Acrylic paint, paper, plastic

Set of 2, 8 x 8 x 8 cm each

Hidden object

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Hidden object

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3