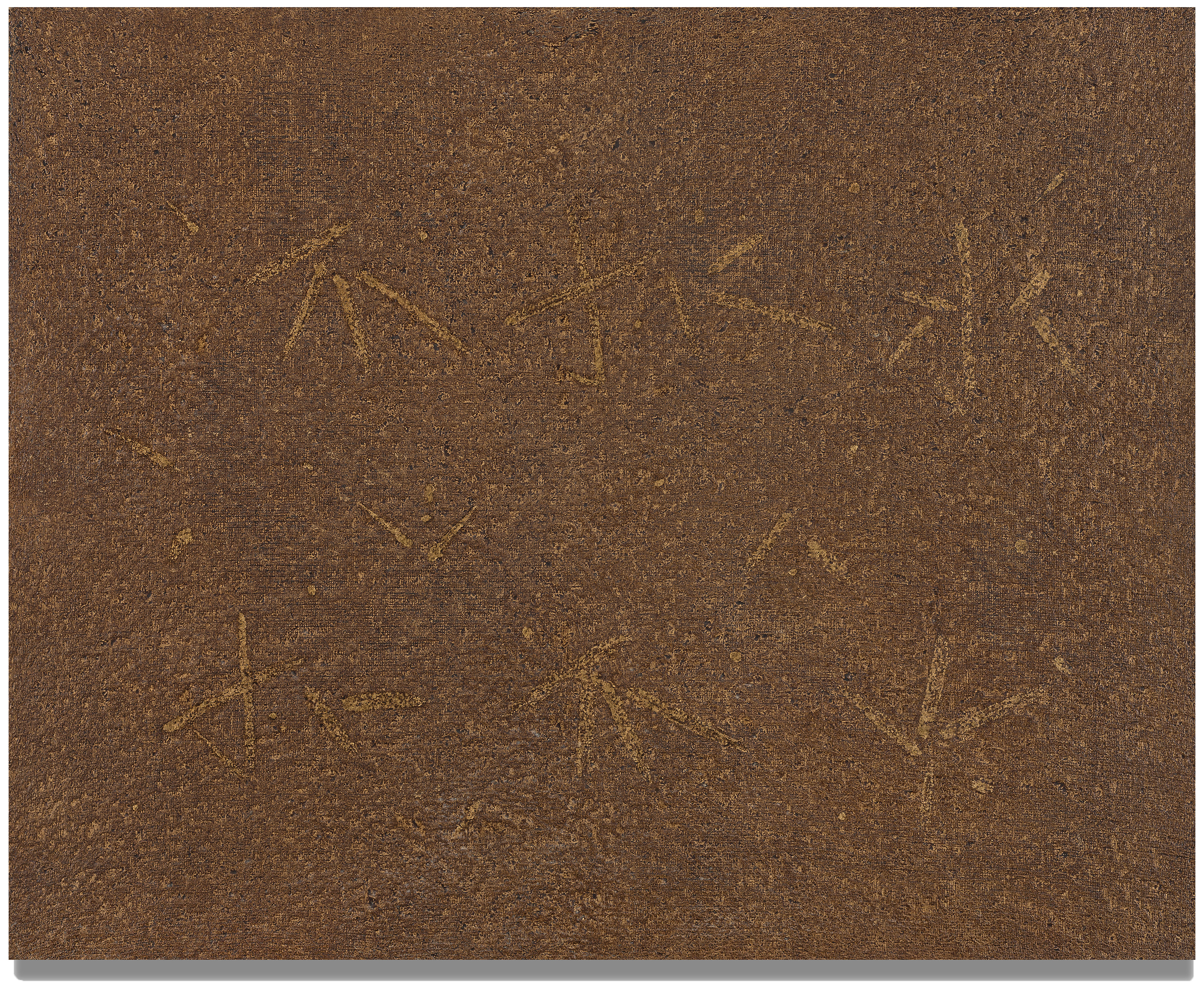

Delicate systematic scratches revealing a dual undertone; rhythmic yet ad hoc strokes whisking the painterly surface; fine wisps skirting the edges of the page. Each are elements composing the delicate, process-driven work of seminal Korean artist Cho Yong-Ik (b. 1934), who rose to prominence in the mid 60s following his studies at Seoul National University before passing in the 70s to the Dansaekhwa rubric of expression[1]. Edouard Malingue Gallery is thrilled to present the first major solo survey of Cho and to investigate how he at once championed its key tenets – repetition, meditation and tranquility through placing the ‘act of making’ at the heart of creation – yet differentiated himself from other Dansaekhwa artists by permitting subtle hints of colour to grace his work and placing a further emphasis on energetic materiality.

Following the period of political turmoil that pervaded Korea in the 50s, a need amongst several artists in the newly established South Korea emerged for reconnecting with their roots of the Chosun Dynasty; those sentiments and habits associated with Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism[2]. Dansaekhwa provided an articulation for this resurgence, through its characteristic of ‘manipulating’ the materials of painting: pushing, painting, dragging it. All, however, without aggression; the effect was rather one of meditative catharsis, an aspect of art production that permits the exploration of soft objects, from rice paper to the pigments used, to the delicate canvas. Melding both pictorial articulation and a level of performance, the works convey a timeless, universal language whilst equally symbolising a ‘liberation’ from strict traditions of Korea’s artistic heritage.

On display will be a select number of works by Cho from the 70s, 80s and 90s, which individually yet collectively illustrate how he followed the key tenets of the Dansaekhwa rubric whilst adding elements of his own. The ‘Scratch Series’ from the 70s, for example, shows his rhythmic gesturing across the canvas, as he pressed off the top layer of paint with his bare thumb to reveal the alter undertone. Whilst following at times the monochromatic painting values ascribed to by other Dansaekhwa artists, Cho equally diverted from it, experimenting with dual tones of vivid reds, oranges and occasionally blues. As such, he added a further layer of vitality to his paintings, emphasising their gestural qualities, whilst bridging a gap with the tonal properties of his ‘Geometric Abstract’ paintings of the 60s.

Following through Cho’s ‘Wave Series’ of the 80s and his later ‘Bamboo Series’ of the 90s, one continues to see this constant push and pull between the monochromatic tendencies of his peers and his more vivacious channeling of the techniques. For the ‘Waves Series’ he delicately, yet with great physical exertion and in a single exhalation, whisked at the surface of each painting, creating minimalist, repeated yet ad hoc sweeps across the surface. Suggesting rather than depicting the sea or the ocean, the viewer at once senses it through the works’ gesturality, and is also left to complete the paintings’ pictorial equation both through their physical presence and gaze. Equally with the ‘Bamboo Series’, the leaves finely appear on the paper, revealing the textures of the materials used. Whereas the image of the bamboo itself is minimalist, two-dimensional and nearly naive, the quality of execution gives the entire series a textural sense of three dimensionality.

Overall, Cho introduces an important angle to the discussion surrounding Dansaekhwa: he identifies as such an artist – his thoughts as well as techniques certainly associate him with this line of action heralding repetition, meditation, and tranquility – yet, he permitted for the insertion of colour. Rather than it distracting from the rubric’s emphasis on meditation, however, it seems to convey the possibility of multiple emotional states, from one of warmth to others of detachment. As such, Cho’s work probes us to consider the diverse formal languages of Dansaekhwa and fleshes out to a greater extent its associations with tactility, spirit and performance.

Cho Yong-Ik has been highly lauded as one of South Korea’s most important painters and recently held a major solo exhibition at the Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul. Further exhibitions include the Samsung Museum of Art, MMCA Seoul & Gwacheon, Arko Art Center Seoul and Fukuoka Museum of Art. Cho’s work has additionally been exhibited in various Biennales, including Paris (1961, 1969), Sao Paulo (1967) and is held in multiple permanent collections, including the MMCA, Seoul Art Museum, Samsung Museum of Art and Gwangu Museum of Art.

[1] Jung Yu-Jin, ‘Korean Painting Now’, 2012

[2] Henry Meyric Hughes, ‘The International Art Scene and The Status of Dansaekhwa’, Art in Asia, 2014

Cho Yong-Ik

1974

Acrylic on canvas

145 x 112 cm

1975

Acrylic on canvas

163 x 131 cm

1975

Acrylic on canvas

163 x 131 cm

1976

Acrylic on canvas

163 x 131 cm

1977

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 97 cm

1977

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 97 cm

1979

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 130 cm

1984

Acrylic on canvas

131 x 162 cm

1984

Acrylic on canvas

131 x 162 cm

1985

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 193 cm

1986

Acrylic on canvas

131 x 162 cm

1990

Acrylic on canvas

132 x 164 cm

1993

Acrylic on canvas

97 x 130 cm

1996

Acrylic on rice paper laid down on canvas

130 x 162 cm