Responding to an interview question in 2014, Hong Kong Chinese artist Ko Sin Tung (b. 1987), said, “We maintain a passionate pursuit of light.” The question had concerned the importance of light to the Impressionists, and suggested that Ko inherits a similar preoccupation. While Ko’s own practice supports her statement literally, she could also have been speaking metaphorically: What is the purpose of artistic inquiry if not illumination, a provocation to truth?

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

Leonard Cohen

For the inaugural show at the gallery’s new address, Edouard Malingue Gallery is delighted to present the exhibition, Invisible Light, from January 15 to March 7, 2015. The group show will feature works by five contemporary artists based in Hong Kong, Istanbul, Paris, and New York, who are interested in exploring, evoking, and manipulating light in their practices with various media and materials: Ko Sin Tung, Nuri Kuzucan, João Vasco Paiva, Eric Baudart and Jeremy Everett.

Of the five, Ko’s fascination with light, as both a theme and a component of her recent work, is perhaps the most direct: “If the purpose of a window is to bring more light into a space, then I wish to take on the role of a window,” she has said of her project, Collecting Light (2014). The installation – a series of painted, archival inkjet prints of internet images depicting homes for rent, enlarged so they become pixelated – was inspired by the advertisement term, tsaiguang, which the artist first encountered in Taipei. The term indicates the presence of a natural light-filled space, which is a common criterion for prospective tenants and homeowners in Taipei, but not, as Ko discovered, in Hong Kong.

Collecting Light examines the different ways in which an individual might perceive and imagine space and light. The work manifests Ko’s concern with a sense of alienation that, for her, pervades modern, urban society. In this context, Ko interprets tsaiguang as not only a measure of an interior space, but also an expression of desire for a good quality of life. Ko’s manipulation, using white paint, of the light in these images transforms them from mundane to surreal.

Nuri Kuzucan (b. 1971), too, uses light in his paintings to explore the malaise of a modern, urban existence; to emphasise what Leonard Cohen called “the cracks in everything”, and what Nietzsche defined, in the modern individual, as a rupture between the inner and outer selves. As the cultural specialist Ariane Koek noted in a monograph published by Edouard Malingue Gallery, Kuzucan’s works, which are driven by “a relentless geometry”, very often represent “architecture in process with light showing through” – that is, creation in flux. Through his paintings’ “lack of fixed perfection”, Kuzucan encourages a mending of the Nietzschean rupture through projection and introspection: The Turkish artist has often said of his works, which focus on architectural structures and are empty of human figures, that the paintings’ humanity derives from the viewer.

From a 2013 interview with Kuzucan, Koek surmised that “the flaws, gaps, shadows and spaces in these buildings… [disrupt] any notion of the solidity of the material world in which we live”, thereby inspiring a process of self-discovery. Kuzucan’s striking use of light, along with elements such as geometry, texture, colour and composition give his works a robust dimensionality that is as visually satisfying as it is intellectually profound.

The structures in Kuzucan’s paintings are nationally, though not temporally, ambiguous – that is, as Koek described, “the buildings could be from everywhere, but not from anytime”. By contrast, João Vasco Paiva’s recent work draws from the dense yet transitory urban environment that is unique to Hong Kong, where the Portuguese artist has been based since 2006. He processes the forms, motifs and other physical marks that he finds in the city to create a cipher or shorthand for interpreting its complex, contemporary landscape.

Paiva (b. 1979) has compared his own studio practice to the research activities – those quests for enlightenment – of early Portuguese colonists in Macau: the artist, too, collects observed phenomena for detailed analysis. “The only [difference is] the value of these objects, or the qualities that I find interesting in them,” Paiva said during an interview in 2014. What fascinates him most is “the act of looking for the algorithmic qualities present in the everyday.”

The piece Blindspots (2014), which was originally shown in May 2014 at ‘Cast Away’, Paiva’s major solo exhibition at the Orient Foundation in Macau, is a grey resin cast of a mat of ground surface indicators, designed to assist visually-impaired passengers in boarding the ferries that run between Hong Kong, Kowloon and the outlying islands. Paiva’s version was placed on the floor near the entrance of the show, conveying, perhaps, a sly message about our perceptions of, and journeys into, the unknown.

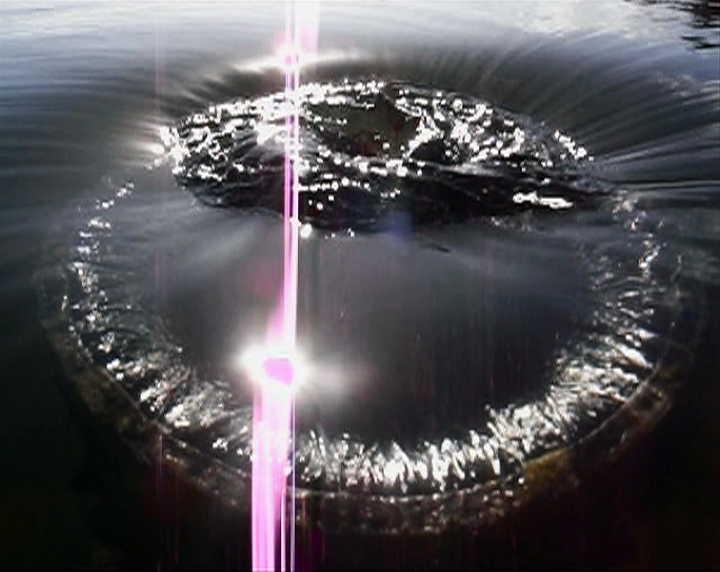

While Paiva seeks to elevate the everyday by paring down and codifying the patterns he finds, to highlight therein some intriguing essence, Eric Baudart’s practice, which also focuses on found objects, owes more directly to Marcel Duchamp’s readymade. The concept was defined by the Surrealists in 1938 as “an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist”. By selecting, as well as experimenting with, ordinary materials, Baudart (b. 1972), who lives and works in Paris, discovers beauty and meaning in the mundane. Scotch (2013), for example, is a scanner photograph of a roll of adhesive tape, printed on tracing paper and laid on alveolar plastic. The work’s abstract composition, soft pink palette, and the alluring way in which the tape has caught the light, demonstrate the aesthetic possibilities concealed within a utilitarian source.

Jeremy Everett (b. 1979) is another who knows the artistic potential of the ordinary, and especially of the ruined. Many of his works explore the interface between beauty and decay – a process that the New York and Paris based artist often provokes and employs as creative input. Everett intervenes in processes and materials, both natural and man-made, subverting their original design to produce new perspectives on the landscapes, physical and psychological, that we inhabit. One of his most sensational video works, Death Valley Vacuum (2010), depicts Everett in the scorching California desert, hovering up the sand, until, for minutes in, the machine breaks down.Death Valley Vacuum (2010), depicts Everett in the scorching California desert, hovering up the sand, until, for minutes in, the machine breaks down.

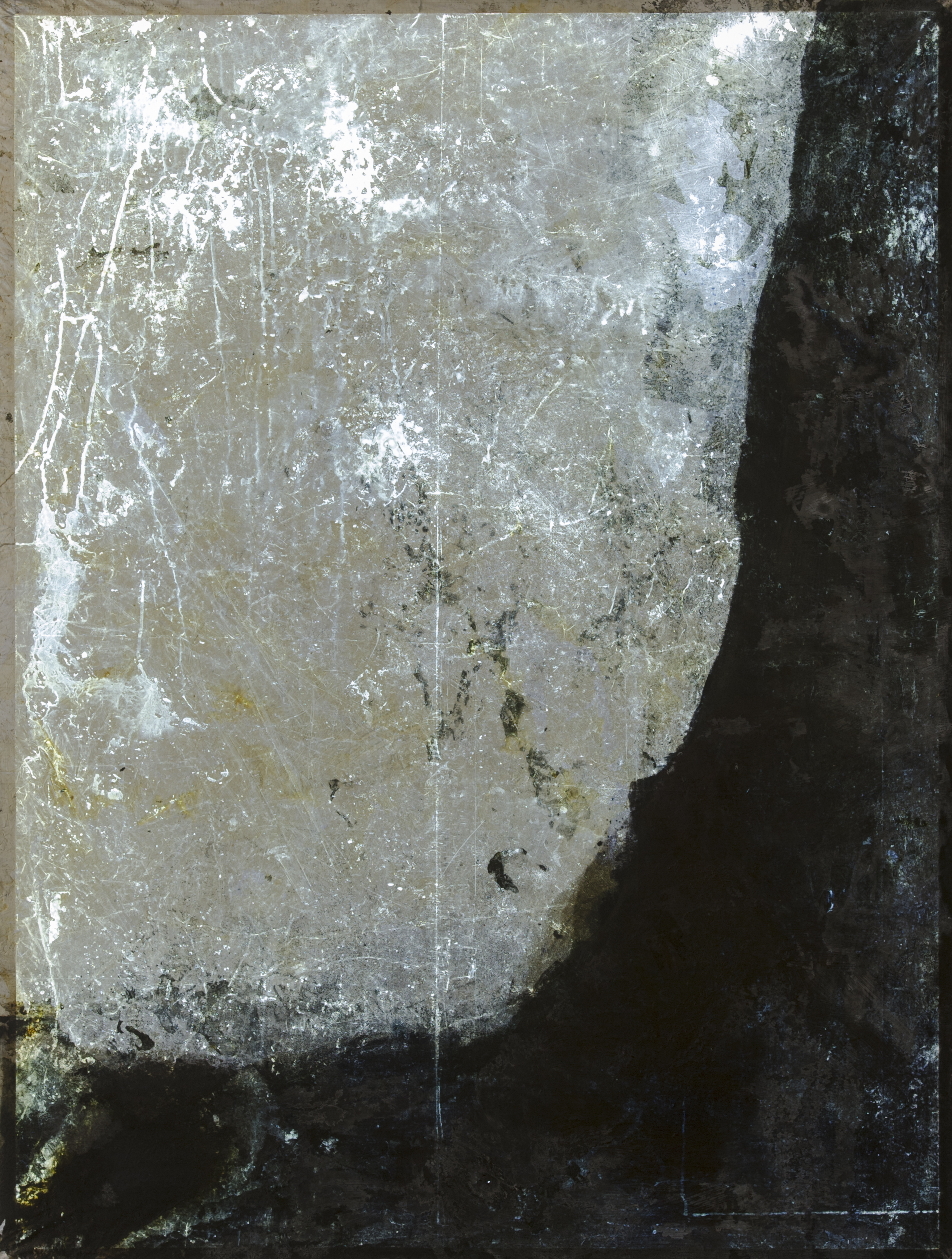

In his recent work, Everett plays with the role of light in photography while disrupting key elements of that process. White Noise (2014), for example, is photography without the photograph as it is usually defined – that is, without a representational image. He made this series of monochrome digital prints by manually opening and closing the back of his analogue camera, producing an effect that is spectral and melancholy.

His Film Still series (2013), moreover, is photography without the camera. To create these, Everett spread gelatin silver emulsion on mylar (the material from which emergency blankets are made) and revealed the pieces to light, thus manipulating techniques of exposure and dark room development, but released from the camera’s mechanics and coaxed into the realm of abstract painting. The industrial palette, the scratches and flaws that appear on the adulterated mylar evoke a derelict glamour, the space between hope and dystopia that seems to represent the fulcrum of Everett’s practice. In both series, as well as in No Exit (2012), Everett uses light as the tool of creation, without knowing fully what the result will be. In this way, his works become organic, their shape engendered by a kind of photosynthesis.

Invisible Light Group Show

2014

Acrylic, archival inkjet print on canvas

Variable Sizes

2013

Silver gelatin print on mylar

131x99cm

2008

video

3min 20sec

Edition 2/5

2015

Polymer varnish on tarpaulin Stay stainless steel rail

280 x 280 cm

2014

Acrylic on canvas

190 x 180 cm