Whether it be of a still-life, figure or landscape, Wang Zhibo’s recent paintings carry a repeated sense of ‘sketching from life’ (xiesheng). Why is this so? Is it because the subjects she paints have no ‘meaning’? Or is it because her paintings do not reflect interrelations of meaning or involve narrativity in a traditional sense? As part of China’s standard art education, drawing or painting from life is considered practice – it is mere preparation for a final ‘meaningful’ creation. Yet, Wang Zhibo’s works purposely linger, or rather, continuously return to this condition of practice.

The question is such: if the subjects of a painting do not have ‘meaning’ then where does the ‘meaning’ of a painting lie?

In 1943, as part of a dialogue between Henri Matisse and Louis Aragon, Matisse remarked, “I don’t mean that by seeing the tree through my window I work to copy it. The tree is also the total sum of its effects upon me.” This is an oft-quoted episode of Western art history: from such beginnings the Modernist subject in painting has been disintegrated, disjoined and dissected until it has become a pure concept or experience only to be referred to and no longer viewed. Yet, what happened later is far from Matisse’s intent (to use Matisse as the paragon of a Great Painter). The pure and unadorned working condition he describes is that free state reached by a modern painter after shaking off the baggage of classical painting history. This freedom, however, ended up being rapidly forsaken by the radical spirit of the age.

Modernism’s historical process of ‘content elimination’ reached an end point after Minimalism. At the same time, visual reality today happens to present a truly ‘contentless’ spectacle in a manner that would’ve been unimaginable to painters throughout history: everyone can attain first hand an utterly ‘contentless’ viewing experience through advertising, surfing the web and science fiction films. But what such experiences bring about is not that pure, spiritual exchange as promised by Modernism but rather Anarchism.

If such a world can be said to perplex ordinary experiences of viewing then for painters it must certainly be incomparably hopeless.

Painters today must seek new methods in order to counter and respond to contemporary conditions of art and reality. Any one image already exists out there and yet this condition is really no different from not-existing. Any image can convey any meaning – the relation between imagery and meaning however has fundamentally changed. Hence, painters today face an exceedingly difficult task—a task that is also exceedingly crucial and exceedingly appealing.

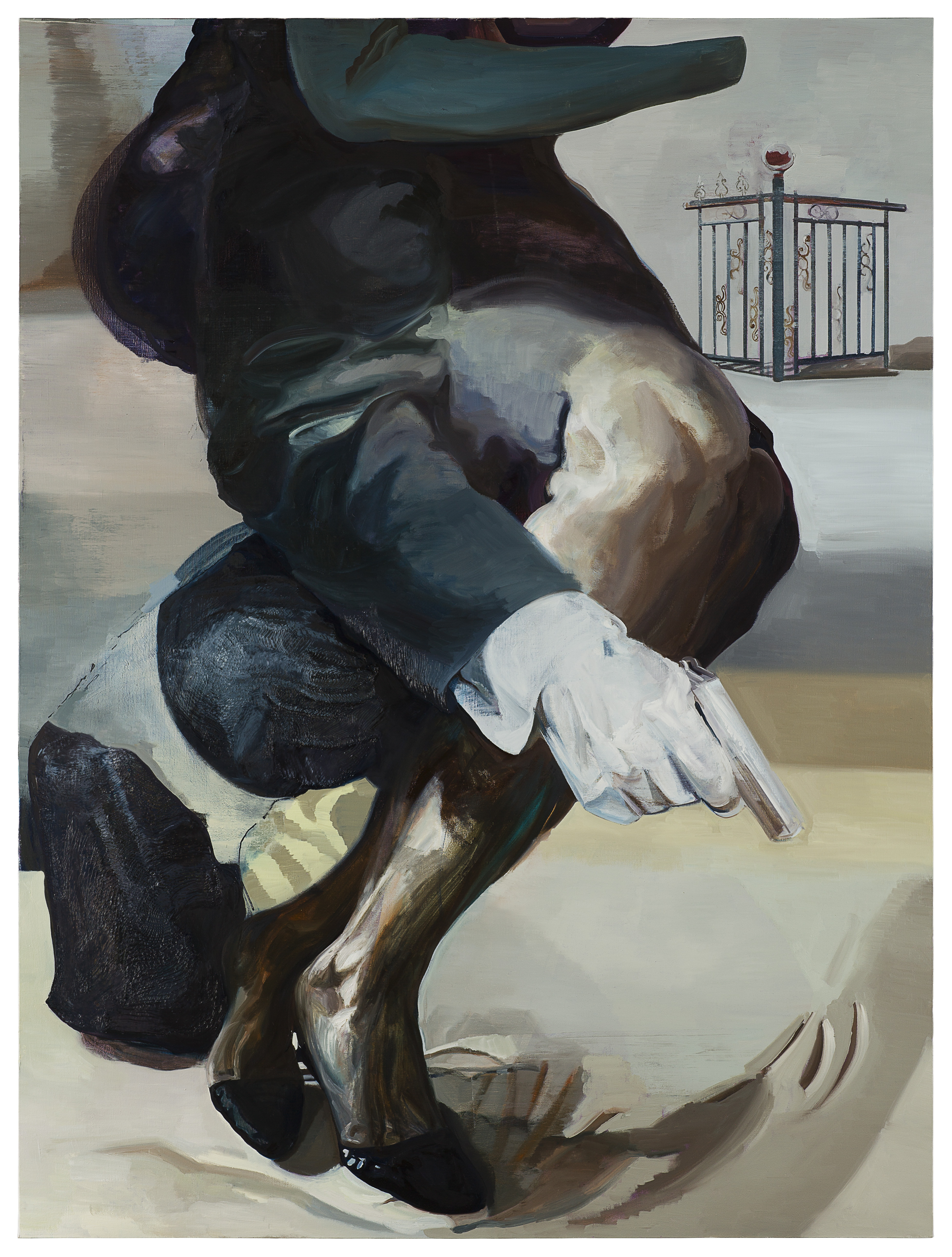

‘He no longer looks human’ is the title of Wang Zhibo’s solo exhibition at Edouard Malingue Gallery, Shanghai. A subject is originally the projection of the human spirit – what Wang Zhibo portrays is the mating and morphing of humans and objects. Humans no longer take on a human form. For Wang Zhibo, bodily flesh, as the abode of life, is the only certainty we have. The human body is the only rock upon which one can have a footing in a world of turmoil and constant upheaval. In Wang Zhibo’s work, the human body—an arm, a leg, a posture, a gesture—is a simple and pure subject not worn out by thinking; to us, it is familiar and yet foreign, the base of life both loved and feared.

In the past few years, Wang Zhibo (like a number of artists) has been using many readymade images from mainstream books, magazines and websites in her paintings. By removing the context, she endeavours to turn these images into ‘material’ instead of pursuing the ‘meaning’ of such ‘materials’, and certainly not pursuing their ‘meaninglessness’. Rather, she simply tries to refine with them a ‘meta-language’ of painting—colours, lines, chiaroscuro, space, amongst others.

It is, admittedly, a makeshift stratagem, a compromised Dada, a blind chance. Yet, this is also an approach that inspires: contemporary painters are returning to the working conditions described by Matisse, in a peculiar way. Just as with drawing or painting from life, painting has again become an uninterrupted everyday experiment. Through the realisation of every painting, painters and viewers of paintings can discover this craft of bodily sensations and discover how, with certain as of yet unnamed ways, they can record the very complex spiritual world of people in the contemporary age.

///

Wang Zhibo was born in 1981 Zhejiang, graduated from China Academy of Art. Lives and works in Hangzhou and Berlin. Wang Zhibo’s works explore the tangibility, complexity and distortion of time and space. Wang challenges the possibilities of these concepts not only within the two dimensional space, but also with the viewer’s perception and participation with the work. Selected solo exhibitions include ‘Standing Wave’, Armory Show, New York, 2013; ‘There is a Place with Four Suns in the Sky-Red, White, Blue and Yellow’, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2016. Her works have also been exhibited at Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, 2007; Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, 2008; Penrith Regional Art Gallery, Sydney, 2014; Chongqing Art Museum, Chongqing, 2015; Villa Vassilieff, Paris, 2017 and Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2017.

He No Longer Looks Human Wang Zhibo

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

Photo © Zhang Hong

‘Immigration policy’s blah-blah- blah’, 2018

Oil on canvas

135 x 180 cm

‘Female! (Self-portrait)’, 2018

Acrylic and oil on canvas

200 x 200 cm

‘Light yellow++’, 2018

Oil on canvas

135 x 180 cm

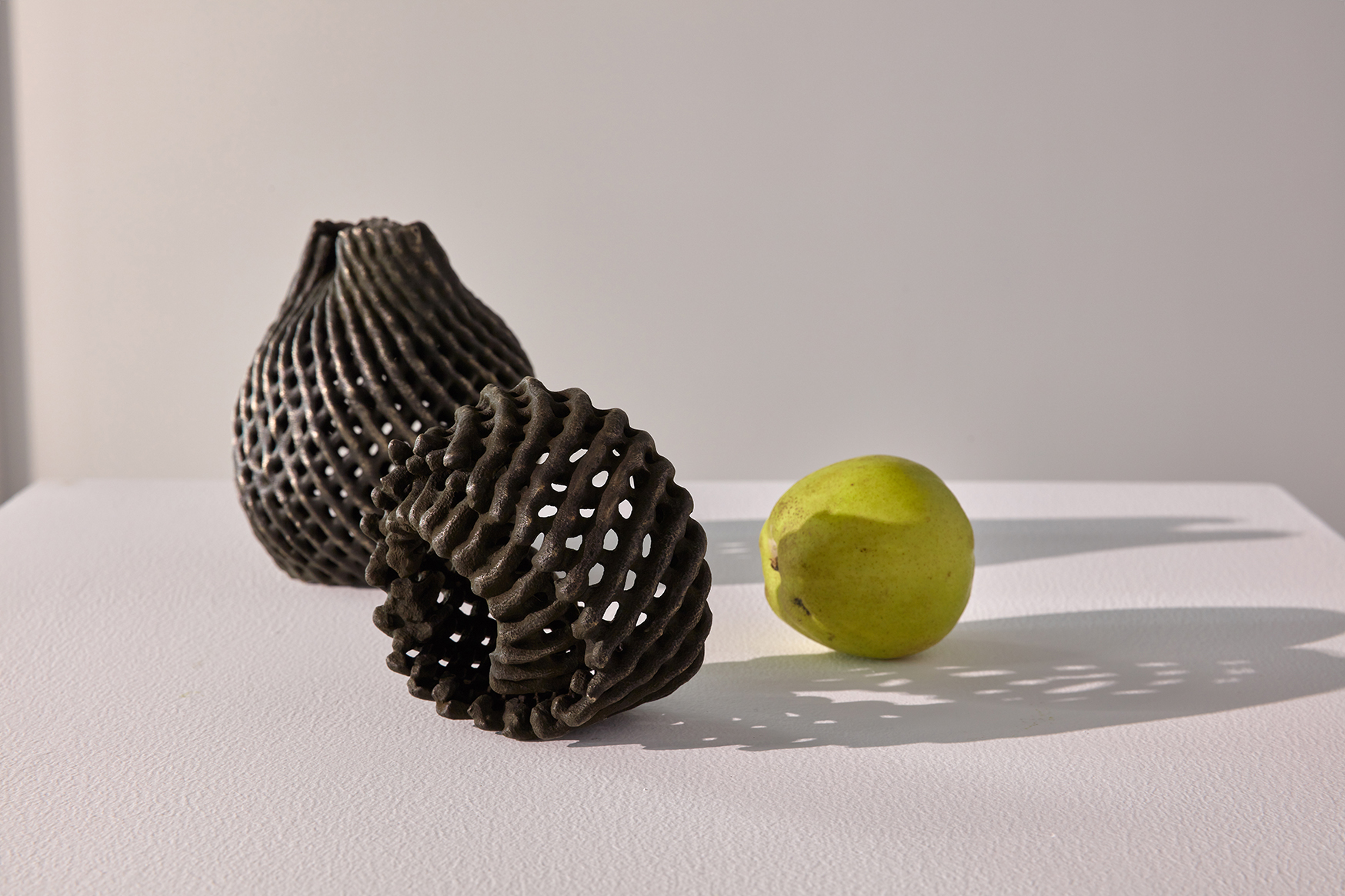

2018

Bronze casted sculptures, fruits

Dimensions variable

2018

Bronze casted sculptures, fruits

Dimensions variable