Since the 2000s, Yeung Hok Tak (b.1970, Hong Kong) has been prolifically depicting people and scenes unique to the land of Hong Kong in rich, at times psychedelic colours, exploring in depth the complicated relationship between nostalgia, memory and social change by making delicate or rough marks on paper and canvas. Over the years, Yeung has developed a singular aesthetic, upon which the artist further forms in recent time an urgent, critical painting practise that is deeply concerned with the social and political of the region. Yeung rediscovers fragments of memory buried deep in the collective consciousness, juxtaposing historical and contemporary subjects in romantic and surreal ways, to question the meaningfulness and legitimacy of historical developments and social progress.

From a graphic design and illustration background, Yeung Hok Tak started publishing his cartoon works and comic strips on the Cockroach in 1998. In his first publication, the semi-autobiographical comic book How blue was my valley released in 2002, he directly confronted nostalgia, and recalled the long-gone scenes of the demolished old Lam Tin Estate where the artist spent his childhood. Nostalgia has been an element of import in Hong Kong and Cantonese contemporary cultures: for years, nostalgic feelings overwhelm cultural fields and realms that are closely tied to consumerism, as northern China cultures are on the rise and becoming invasive. Reminiscing over the glory of the Hong Kong film industry, revisiting the golden age of Hong Kong pop music, or leafing through Hong Kong cartoons, comics or manga that hold a unique position as it bridges local visual and literary cultures — nostalgic practises are one of the most prominent expressions of Hong Kong’s identity politics. The nostalgic tendency re-states the genealogical relationship between the locals and their cultural belongings, negotiating the distances with foreign, at times threatening cultures, and with the present, drastic social change. All of Yeung’s nine cartoon books to date tackle the profound theme of nostalgia and memory by closely examining the urban landscapes of Hong Kong in the 1980s and 1990s, childhood memories and the total transformation of local social cultures.

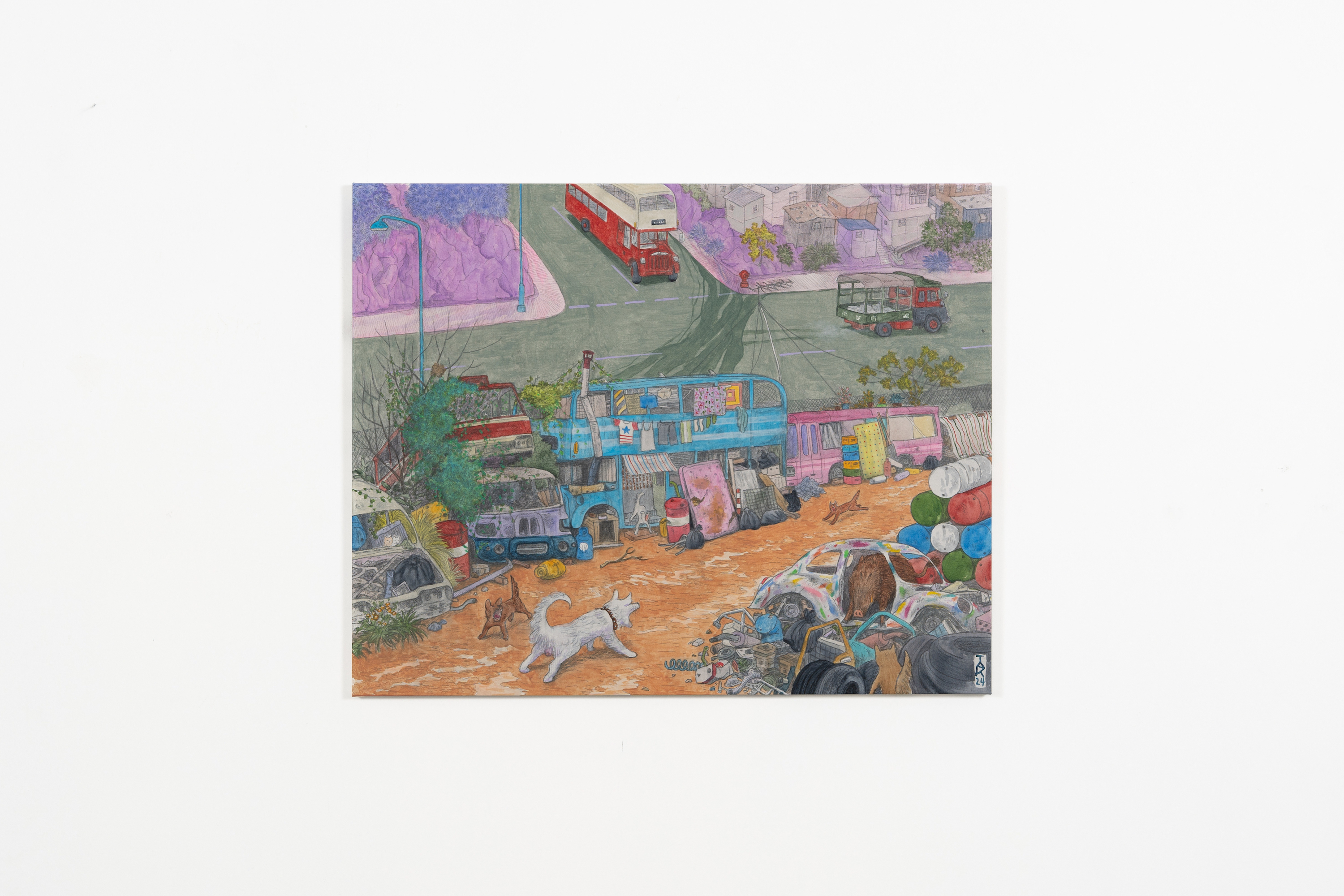

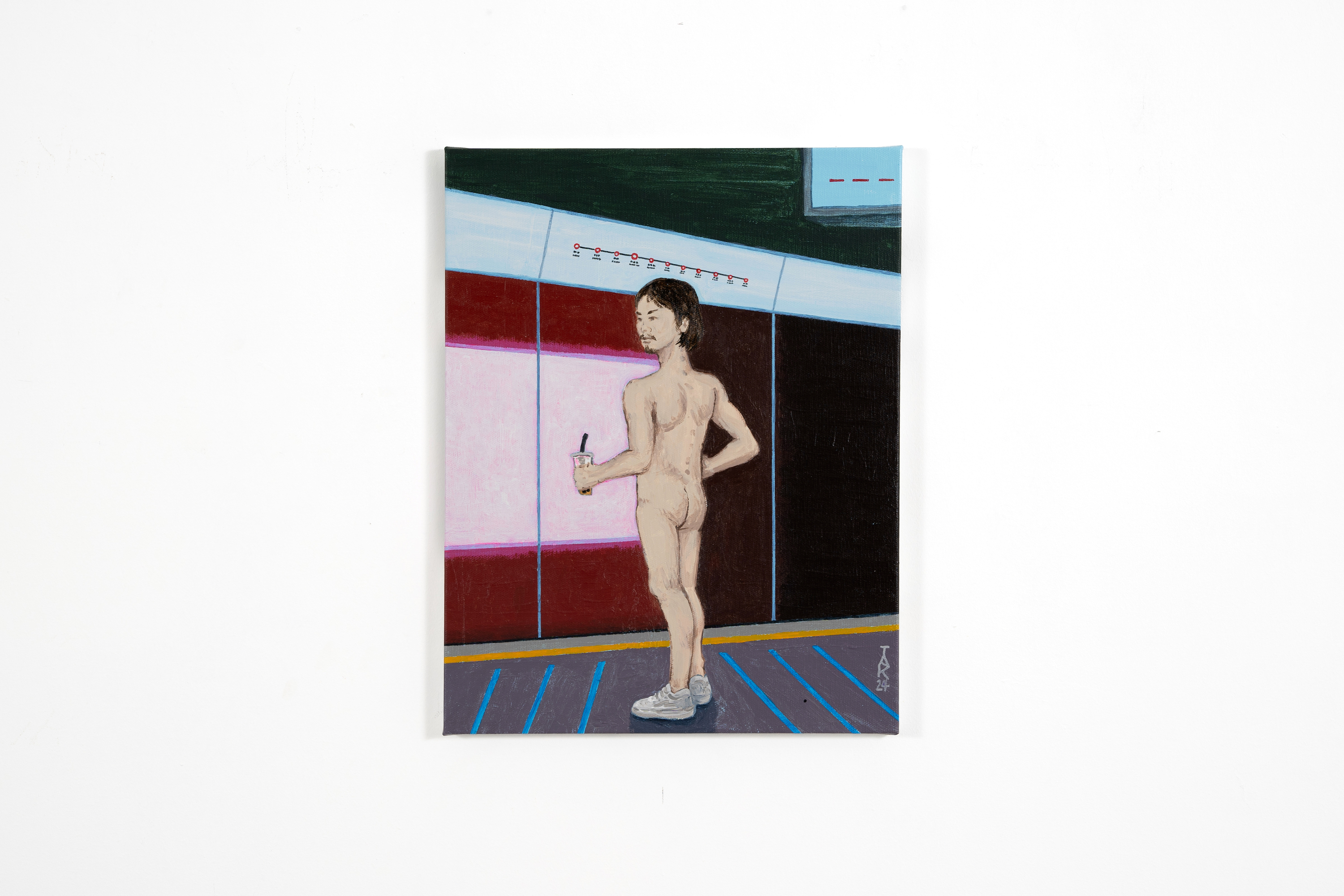

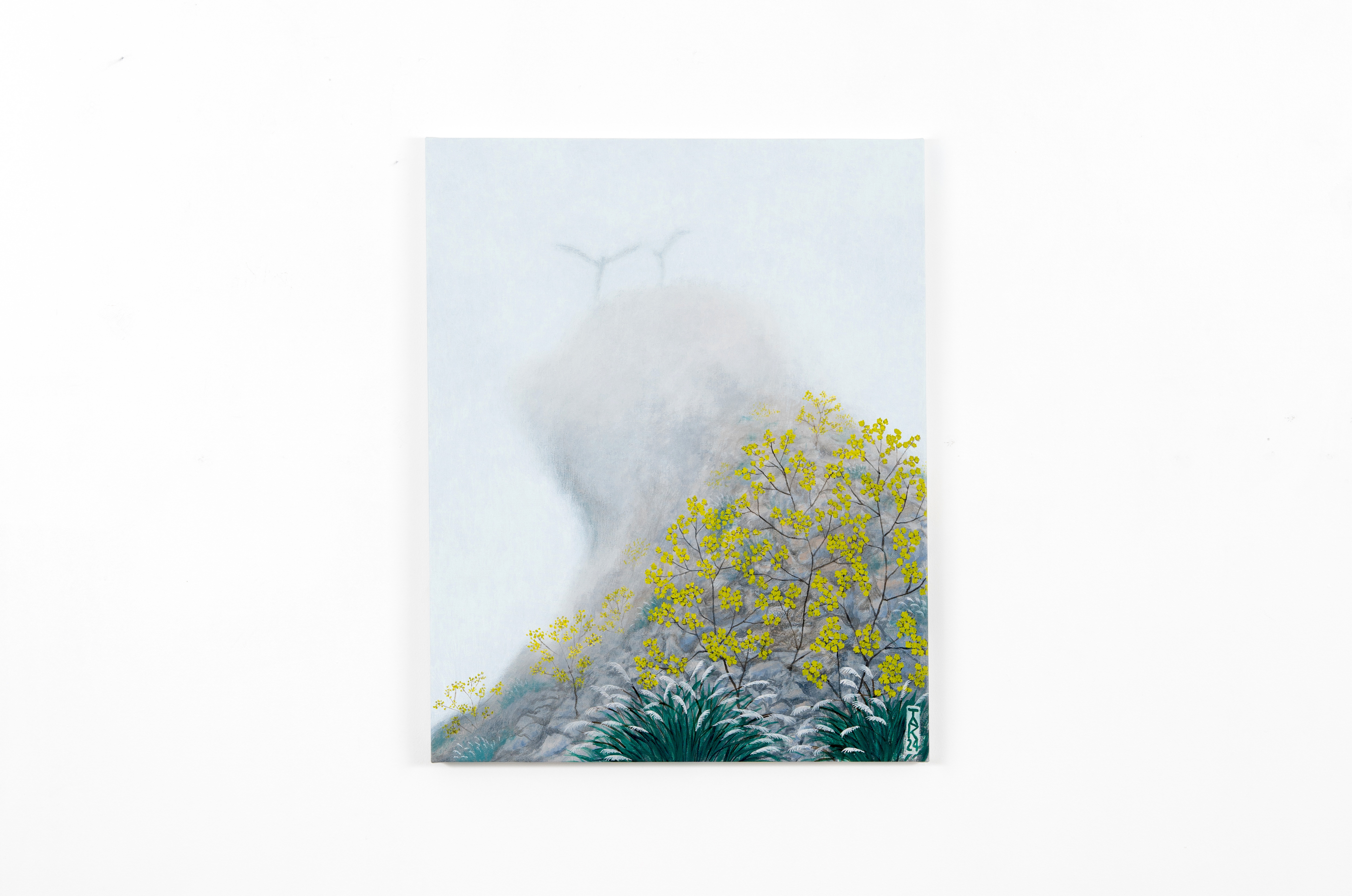

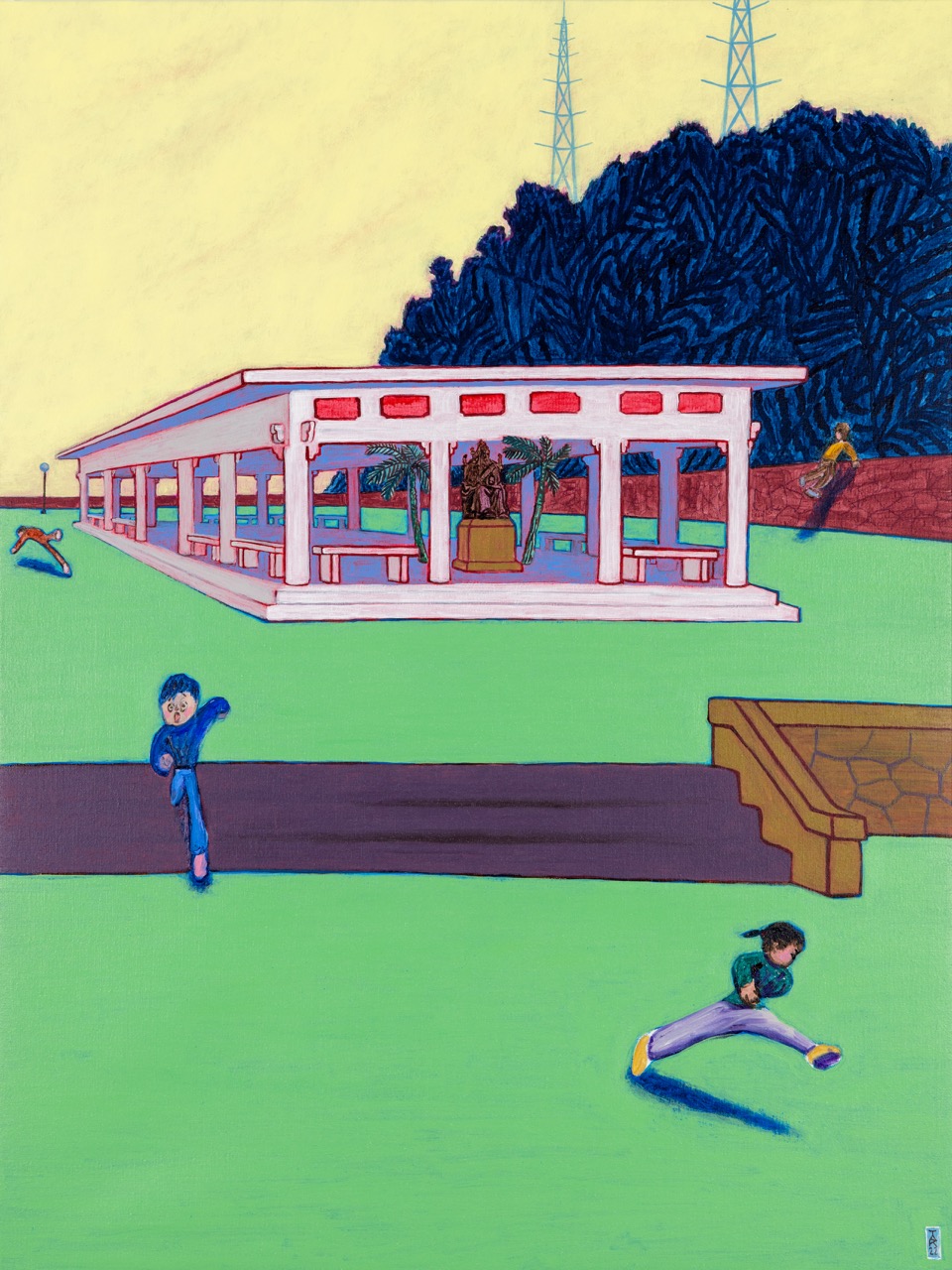

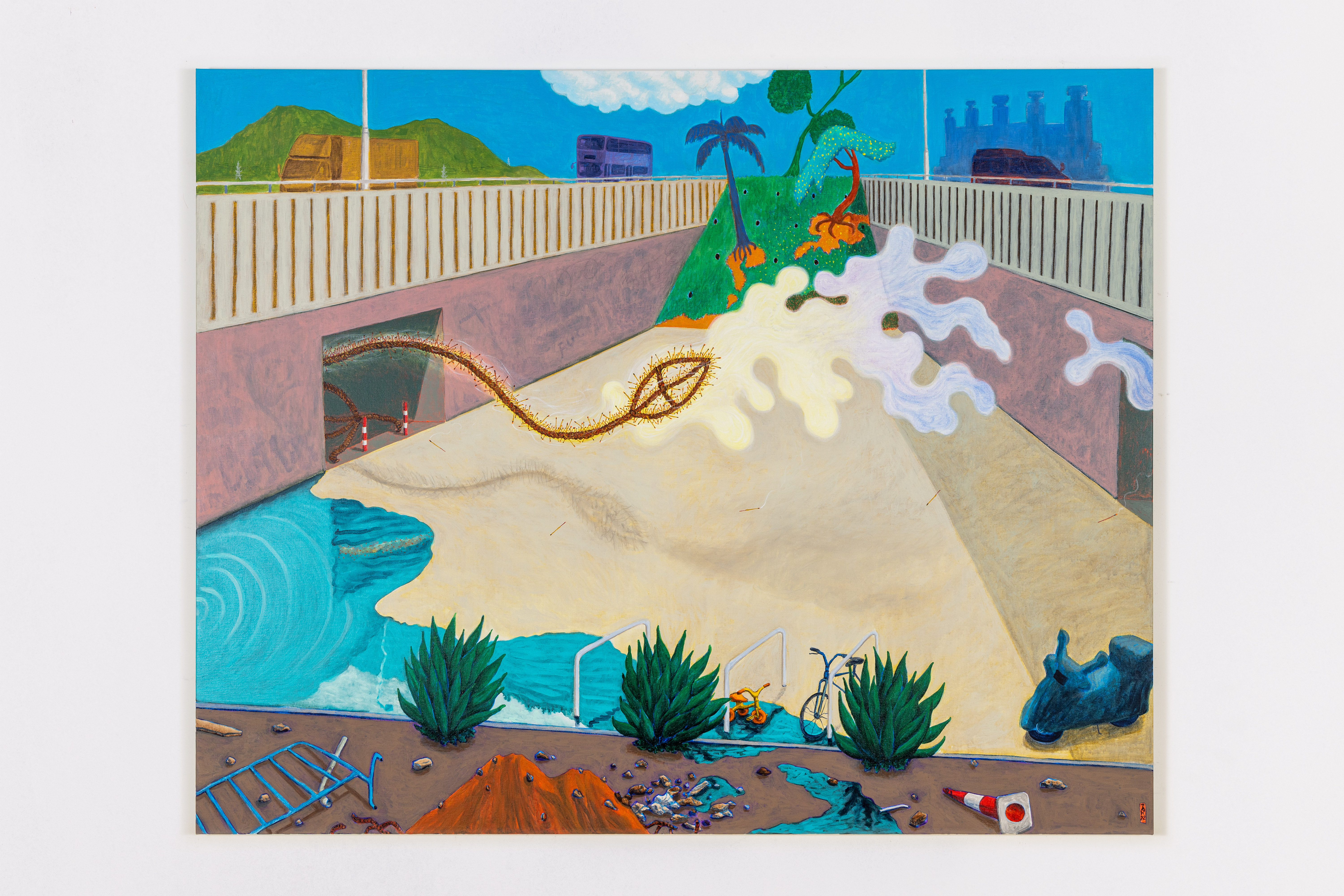

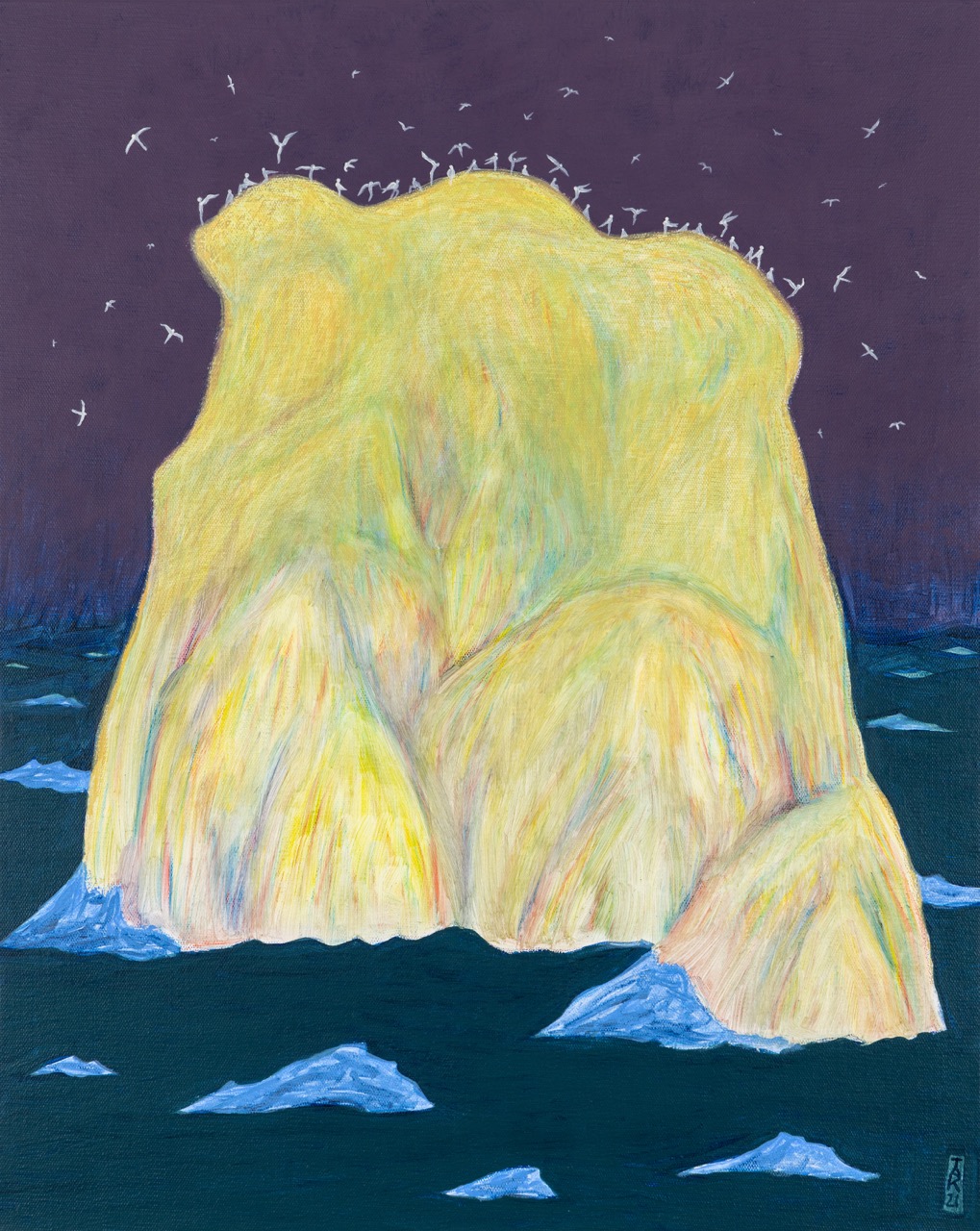

In Yeung Hok Tak’s paintings, his treatment of nostalgic themes differ largely from representations of nostalgia in general. Viewers can rarely spot in his recent series clichéd characters and scenes that are mostly associated with convenient, consumerist stereotypes of Hong Kong; Yeung’s favoured iconic elements — from clustered residential buildings, isolated mountains and isles, double-decker buses, Queen’s Pier, or the Victoria Harbour Clock Tower erected in 1915 — are frequently transplanted into surreal contexts, crystallised in void, sparsely populated environments. Yeung sometimes presents excessively emptied canvases, found in which are subject matters that are relic-like, theatricalised, tranquil yet absurd. Be it an isolated rock mountain frequented only by avian beings (The Lion in Winter, 2021), a speedy street brawling scene (Oh, A Royalist!?, 2022), or human figures and fantastic creatures escaping towards outside of the canvas (Defy Slippery, 2022, or Enter The Fire Dragon, 2022) — Yeung’s subjects are rendered passionately cold, as radicalised and isolated fragments of memory tend to be.

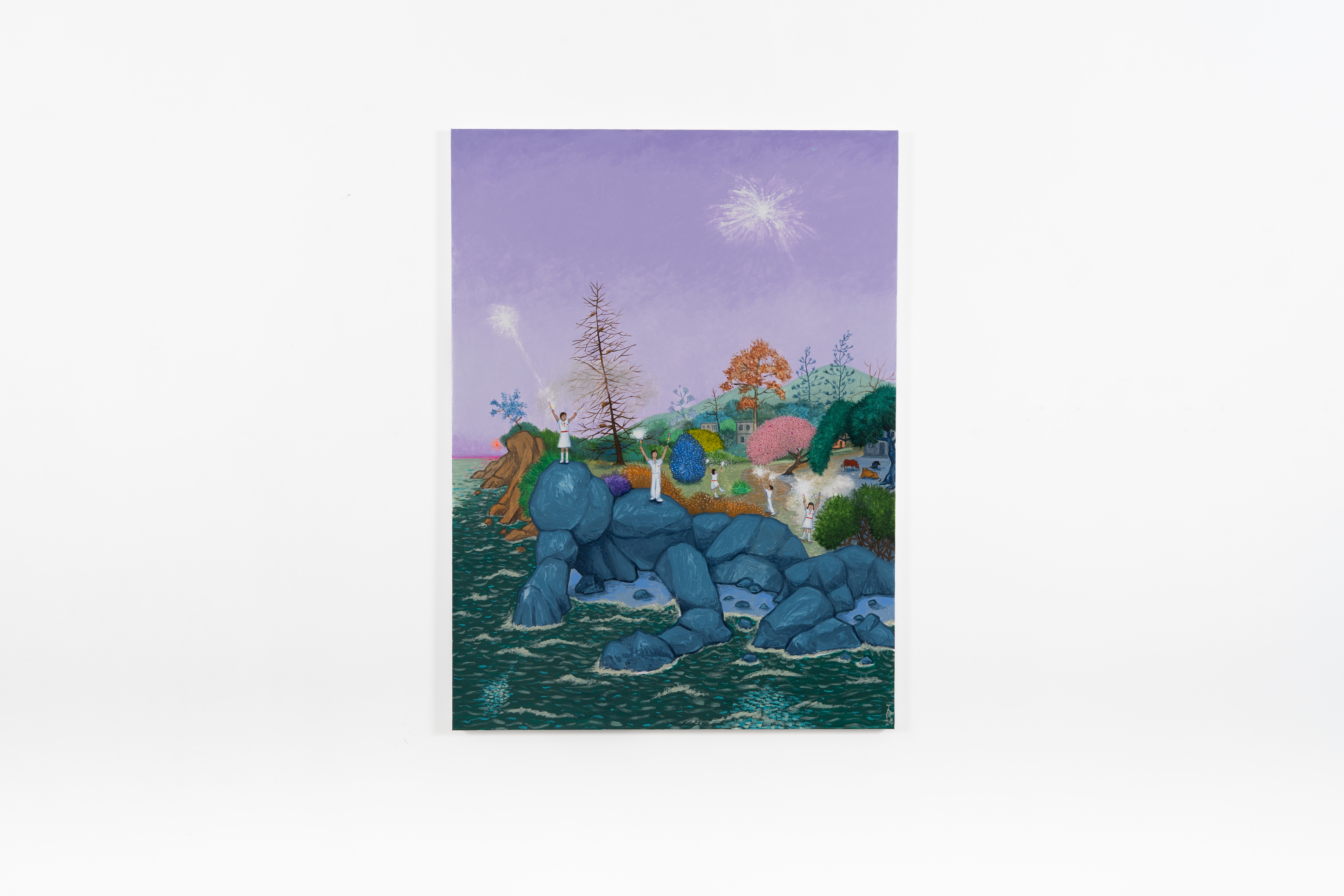

Speaking of his recent paintings, Yeung Hok Tak admits that he is less interested in treating Hong Kong as an isolated exception than to consider the city’s history and future from a greater geopolitical perspective. His recent exhibition at Kiang Malingue, “What a big smoke ring” in 2022 speaks of the artist’s ambivalence regarding nostalgia, history and memory: on the one hand, Yeung in his signature fashion supplements the series of luscious paintings with texts that are often unequivocally cynical and irreverent regarding recent developments and crises. The artist’s text for Crackling, Spluttering, Roaring (2022) for example, reads: “…Let’s embrace the bright future, splash tear jerking fireworks, until all break down in tears.” For I Will Come for You (2022), Yeung writes: “Can I leave now? I am so bored. I need to go dine, shop and see movies, go to the gym, the club and the karaoke, get a haircut, a lipo and a facial, play mah-jong, cards and bet on horses… Nope, there are no other activities. What other schemes do you think I am up to?”

On the other hand, regarding his oeuvre as a whole and the appearance of nostalgic gestures, Yeung acknowledges the fallacy of brooding over the good old days. The past is not simply superior, and one has to be attentive to means through which histories are manipulated and fabricated. Narrating the story of a friend who either stubbornly refuses new technologies, or has simply disappeared in I Don’t Have Any Smart Phone (2021), or rewriting old Victoria’s reluctance regarding interacting and playing with “us” in Play Hide-and-seek with Victoria (2022), Yeung has in recent years presented artworks that are ever more complicated in terms of both staging conflicting views, and producing forms that grow organically from his early cartoon works and other inspirations from art history.

Yeung Hok Tak Hong Kong, B. Hong Kong , 1970

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

Installation view, Yeung Hok Tak “I See You There”, Kiang Malingue, Tin Wan, Hong Kong, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Kiang Malingue.

183 x 137 cm

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 91.4 cm

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm each

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 152.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

45.7 x 35.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 152.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 91.4 cm

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 91.4 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 91.4 cm

Acrylic on canvas

122 x 152.5 cm

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

Acrylic, coloured pencil and oil on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm

What A Big Smoke Ring at Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 2022

Acrylic and oil on canvas

76.2 x 60.9cm

Oil on canvas

76.2 x 60.9 cm