A chamber where the sole reverberating sound is your own breath; cellos played against an accentuated mountainous green backdrop; conical shells as coated headphones – these are disparate yet interlinked examples of the delicate, lyrical humour that pervades Su-Mei Tse’s (b. 1973, Luxembourg) practice, which spans video, installation and sculpture. A trained classical cellist of Chinese and British descent, Tse weaves a meditative, “visaural” tale empowering the language of music as a primary voice. Investigating associations between places, geographies, cultures, traditions, Tse’s work elicits a cross-stimulation of the senses, where time and its flow are suspended in a gentle state of contemplation.

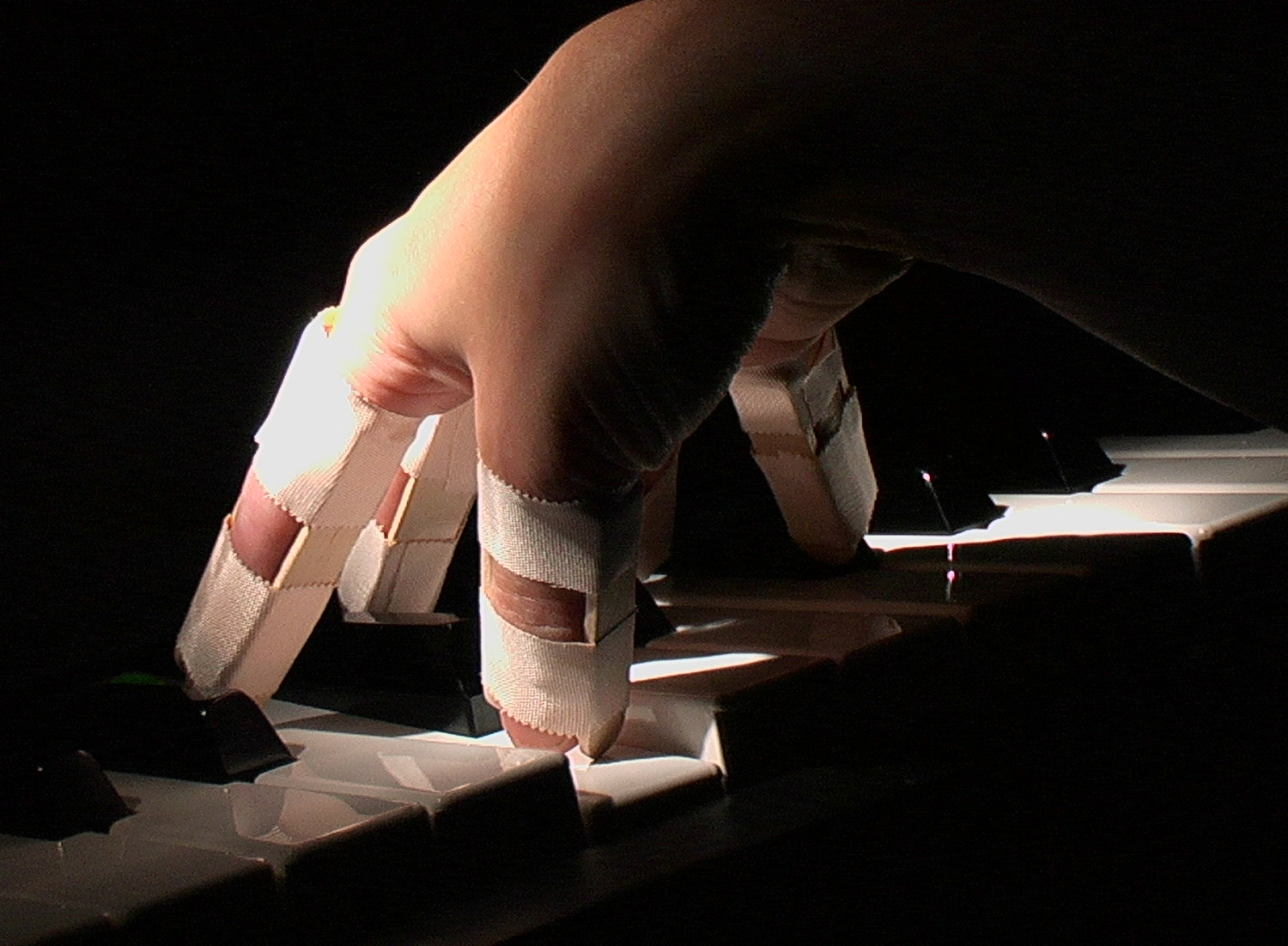

At the heart of Tse’s practice is its relationship with musicality. Brought up by a violinist father and pianist mother, Tse initially studied at the Luxembourg and Paris conservatories before pursuing fine arts studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. From ‘Das Wohltemperiete Klavier’ (2001) to ‘Chambre Sourde’ (2003), Tse explores a range of relationships with sound, from the literal to the more abstract, each time placing music as the prime conveyor of her conceptual pulse. In the former video work, for example, Tse shows a close-up of a pianist’s bound-up hands as they voraciously and determinedly play one of JS Bach’s 48 keyboard preludes and fugues. Repeatedly missing the correct notes, Tse points to the journey towards mastery and conquering of doubt. Conversely, the latter is an installation, which as an anechoic chamber, invites a contemplation of silence. Linking to the Ancient Greek Sceptic’s concept of ‘epoché’, there is a state of suspension as the oral clutter one is accustomed to is blocked, leading to an intellectual pause and attainment of self-consciousness.

Tse contemplates a range of subjects, including the dichotomy of cultures and place. Responding to her personal Eurasian background, certain works flesh out her relationship with Asia and the West whilst simultaneously diverting from the clichés associated with each. ‘Dong Xi Nan Bei (E, W, S, N)’ (2006), for example, is an installation of four neon Chinese characters, each signifying a cardinal point. Beyond the work’s relationship with her personal origin, it equally points to Tse’s running interest in Japanese culture by being arranged according to Japan’s azimuth direction. ‘Standard Eye Level’ (2006) also exemplifies Tse’s nuanced contemplation of cultural variance; an installation work consisting of numerous bonsai plants, each is placed on a horizontal line of fluorescent orange tape stuck on the gallery walls. Originating from not only Japan and China but also Europe and Oceania, each plant is placed on a tripod adjusted to the standard eye-level of the residents in the country – a reflection on both the standards pertaining to each culture as well as a visual metaphor for how environments impact each and everyone’s development.

Amidst the musical and cultural currents in Tse’s work is additionally a strong sense of poetry and nuanced humour. From ‘SUMY’ (2001) to ‘L’Echo’ (2003) and ‘Les Balayeurs du Désert’ (2003), there is a running sense of delicate wit. ‘SUMY’, for example, made in collaboration with Tse’s partner Jean-Lou Majerus, is a pair of light-brown seashells enclosed in a transparent red cube, a cloth interconnecting the units in order to resemble a pair of headphones. Playfully combining her name with that of Sony, the sculpture evokes the aural experience of listening to the ocean via a seashell. ‘L’Echo’ further explores this sense of play: a large video projection shows Tse herself playing the cello on a lush mountainside in the Alps. The romantic setting is somewhat ridiculed, however, by the over-dramatisation of the picture composition, chiefly the sharp contrast between her red costume and the saturated green of the mountain grass. Additionally, the melody she plays echoes amidst her surroundings till it falls out of sync, the setting seemingly carrying both the music and her into the distance. ‘Les Balayeurs du Désert’ further fleshes out this relationship with the landscape by showing a group of men dressed in Parisian street cleaners’ uniforms sweeping a desert in a continuous loop, the futile motion tracked by the sound of their movements.

Overall, Tse’s work poetically draws us into contemplation of our sense of place, self and time, using the universal language of music to at once suggest trains of thought but ultimately allow us to formulate our own. Balancing Tse’s research-driven, intellectually-complex practice is a subtle sense of humour, which lends to an overall delicate dialectical sense of play as well as approachability. Tse’s practice is ultimately not just seen, it is heard and felt; a complete multi-sensory experience that plunges one into a state of suspension.

Su-Mei Tse is an internationally-celebrated artist who rose to prominence in 2003 when she represented Luxembourg at the Venice Biennale and was awarded the prestigious Leono d’Oro award for her tripartite installation ‘Air Conditioned’. Tse’s work has since been exhibited nationally and internationally including solo shows at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taipei (2019); Yuz Museum, Shanghai (2018); Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau (2018); Mudam Luxembourg, Luxembourg (2017); Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona (2011); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (2009); Art Tower Mito, Japan (2009); Seattle Art Museum, Seattle (2008); PS1, New York (2006); Casino, Forum d’Art Contemporain, Luxembourg (2006); Renaissance Society, Chicago (2005); Moderna Museet, Sweden (2004). Group exhibitions include Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany (2009); National Gallery of Art, Poland (2009); Singapore Biennale (2008); Kunsthaus Zurich (2006); De Appel, Amsterdam (2005); Sao Paulo Biennale (2004). Tse has additionally been the recipient of multiple prizes, including the Prize for Contemporary Art by the Foundation Prince Pierre of Monaco (2009) and the Edward Steichen Award, Luxembourg (2005).

Su-Mei Tse Berlin, Germany, B. Luxembourg, 1973

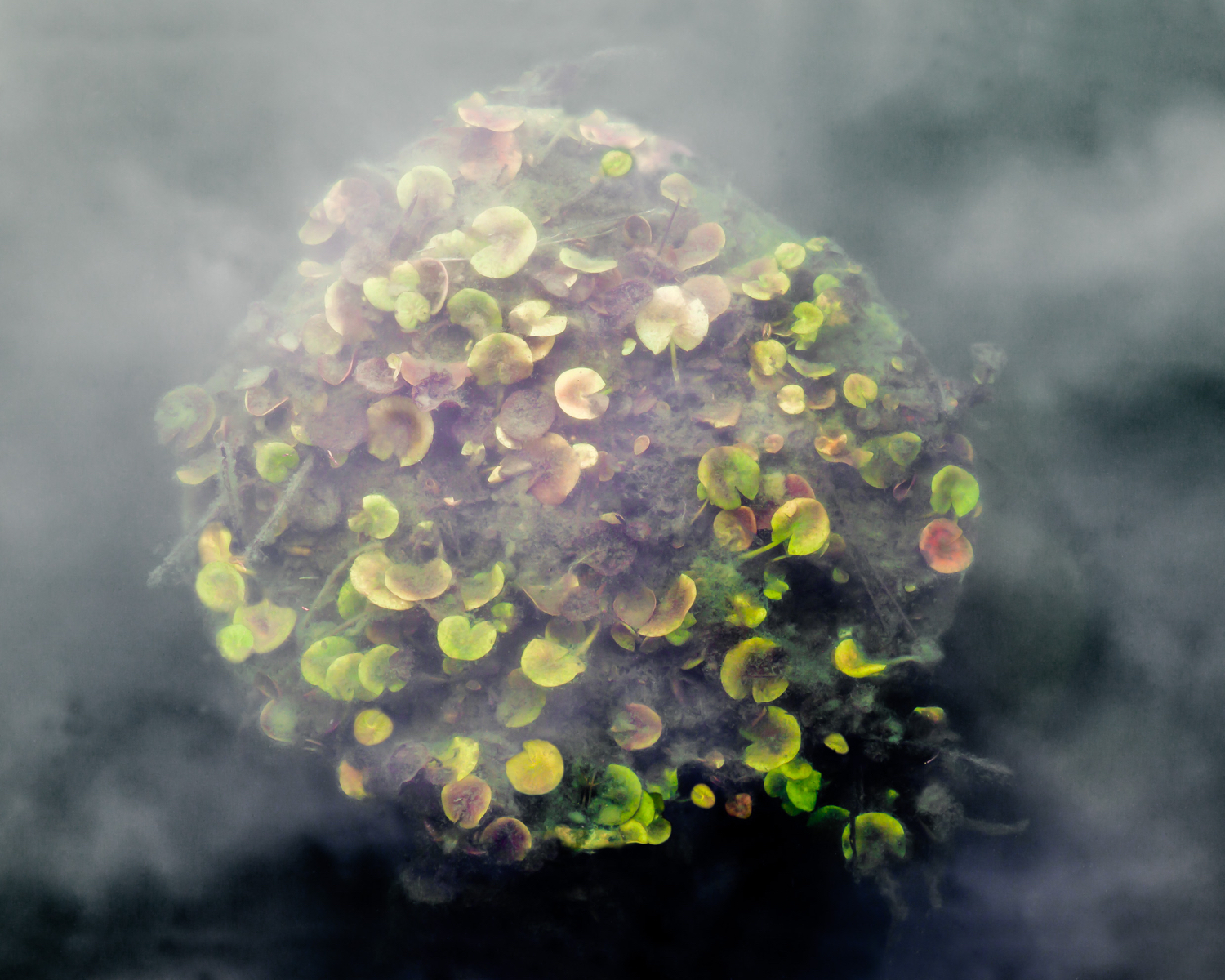

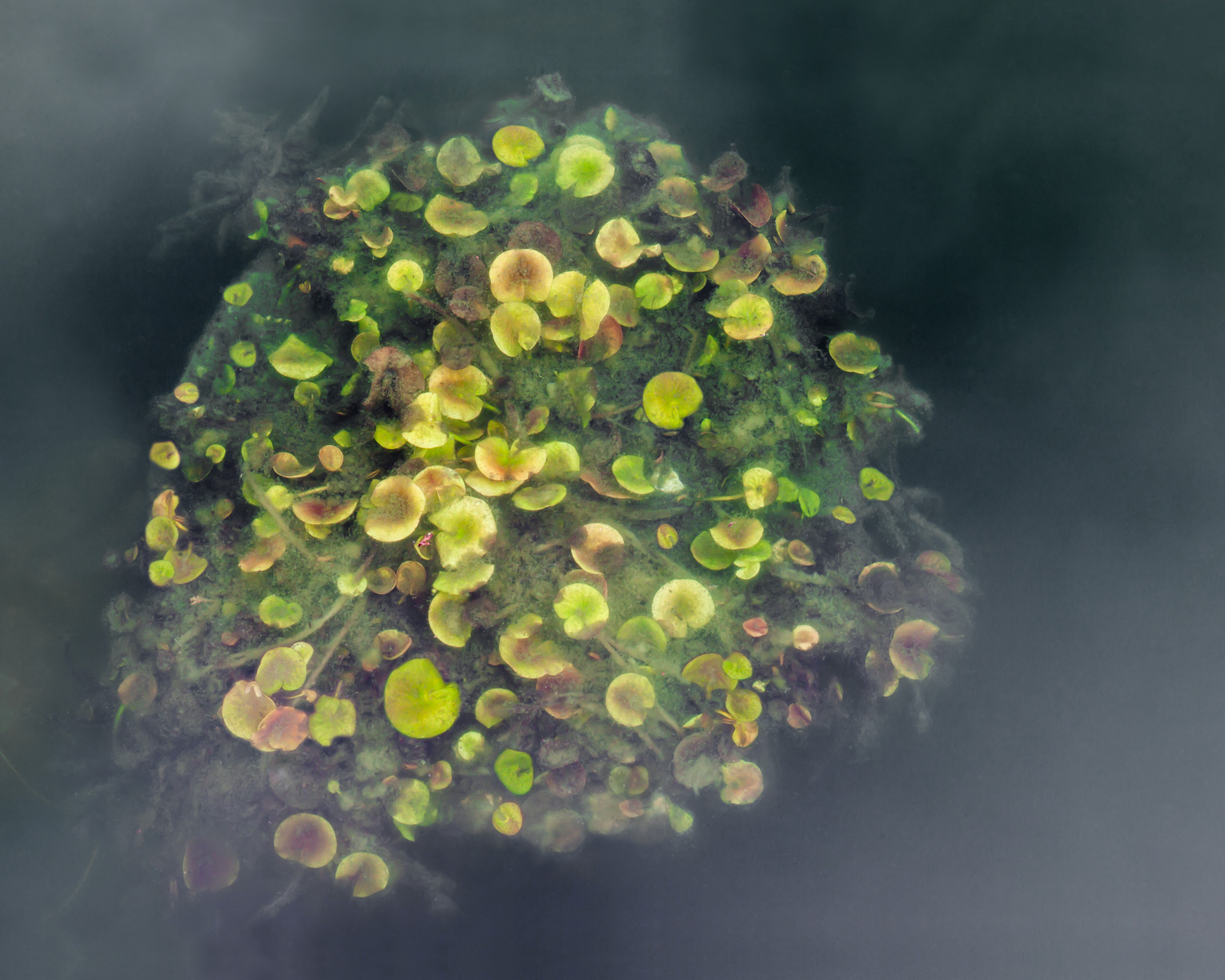

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Daydreams”, Kiang Malingue (Sik On Street), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Su-Mei Tse: Selected Works”, Kiang Malingue (Tin Wan), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Su-Mei Tse: Selected Works”, Kiang Malingue (Tin Wan), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Su-Mei Tse: Selected Works”, Kiang Malingue (Tin Wan), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Su-Mei Tse: Selected Works”, Kiang Malingue (Tin Wan), Hong Kong, 2024.

Installation view, “Su-Mei Tse: Selected Works”, Kiang Malingue (Tin Wan), Hong Kong, 2024.

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Magic Square: Art and Literature in Mirror Image”, Beijing Biennial, 2022,Beijing, China.

Image courtesy of the artist. Photo by Yang Hao.

“Art at Qiaoshan” Guangdong Nanhai Art field Project, Foshan, Guangdong, China, 2022

Image courtesy of the artist

“Art at Qiaoshan” Guangdong Nanhai Art field Project, Foshan, Guangdong, China, 2022

Image courtesy of the artist

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

“Memory Palace in Ruins”, C-LAB, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023

Photo by One Work, Goway LU

Silver gelatin photograph on Dibond and oak wood frame, 120 × 145 cm

Installation, inkjet on fine art paper mounted on Dibond, oak wood frame, wood sticks and steel frame pedestal, dimensions variable

Video projection with sound, 11 min 50 sec, loop

‘Land of the Lustrous’ at UCCA Dune, Aranya, Beidaihe, China

‘Land of the Lustrous’ at UCCA Dune, Aranya, Beidaihe, China

‘Nested’, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2019.

Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

‘Nested’, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2019.

Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

‘Nested’, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2019.

Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

‘Nested’, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2019.

Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

‘Nested’

Yuz Museum Shanghai

2018

Photo by JJYPHOTO

Courtesy of Yuz Museum

‘Nested’

Yuz Museum Shanghai

2018

Photo by JJYPHOTO

Courtesy of Yuz Museum

‘Nested’

Yuz Museum Shanghai

2018

Photo by JJYPHOTO

Courtesy of Yuz Museum

‘Nested’

Yuz Museum Shanghai

2018

Photo by JJYPHOTO

Courtesy of Yuz Museum

Image courtesy of Hayward Gallery

Image courtesy of Hayward Gallery

‘Nested’

Mudam Luxembourg

2017

Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

2017

Installation view at ‘Nested’, Mudam Luxembourg, 2017

Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

2017

HD video projections

4 min 27 sec loop

Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

2009-2017

Installation, ink, stone and iron casted fountain centre piece

110 x 110 x 200 cm – Diameter 350 cm

Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

2011

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Moving sculpture with sound, brass, glass, step motors, synchronized sound system, with pedestal

Sculpture: 95 x 75 x 75 cm, Pedestal: 121 x 50 x 50 cm

Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

2017

Limestone, polished mineral balls

23 × 39 × 30 cm

2017

Wood (maple, cherry, pine, walnut, ashtree and oak), hooks, cable, resin

Dimensions variable

2017

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Sculpture, marble, aluminium

140 x 140 x 3 cm, marble diameter 113 cm

2017

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Sculpture, marble, aluminium, wood, resin

140 x 140 x 3cm, marble diameter 113 cm

‘Moony Tunes’, Setouchi Triennale

2016

Courtesy of Setouchi Triennale and the artist

2015

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Floor sculpture of two ink jet color prints and two glass plates

Prints 147 x 118 cm

Glass plates 100 x 100 x 1.3 cm

2015

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Floor sculpture of two ink jet color prints and two glass plates

Prints 147×118 cm

Glass plates 100x100x1.3 cm

2015

Inkjet printed on archival paper mounted on Dibond 120 x 96 cm

2015

Inkjet printed on archival paper mounted on Dibond 120 x 96 cm

2015

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Single channel HD video

7 mins 50 secs

2015

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Single channel HD video

7 mins 50 secs

2015

HD video Projections

2014

HD video Projections

2014

Moss installation

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Natural moss, wood, mixed media

7 x 4 m

2014

Single channel HD video

12’’ loop

2011

9 tree trunks, motorized system, vegetal elements, sound system

Dimensions variable

“Elegy”, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017

“Elegy”, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017

“Elegy”, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017

“Elegy”, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017

2009-2017

Installation, ink, stone and iron casted fountain center piece

110 x 110 x 200 cm

Diameter 350 cm

2009

High Definition, Video Projection

12 mins, looped

2007

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Diameter 320 cm, total height 545 cm

2007

In collaboration with Jean-Lou Majerus

Diameter 320 cm, total height 545 cm

2007

HD video, colour, sound

7 mins 43 secs

2007

HD video, colour, sound

7 mins 43 secs

2006

Plants, metal supports, fabric, fluorescent lettering and line

Dimensions variable

2006

Neon installation

4 Chinese turquoise neon characters, transformers

60 x 60 cm each

2004

Vertical video projection, colour, sound

3 mins 30 secs loop

2003

Single channel video

5 mins 30 secs looped

2003

Single channel video

4 mins 55 secs looped

2003

Installation

Electric bulbs, foam structure

2001

Headband, velvet, shells, resin and lettering

2001

Video projection, colour, sound

5 mins

2001

Video projection, colour, sound

5 mins